![Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend]()

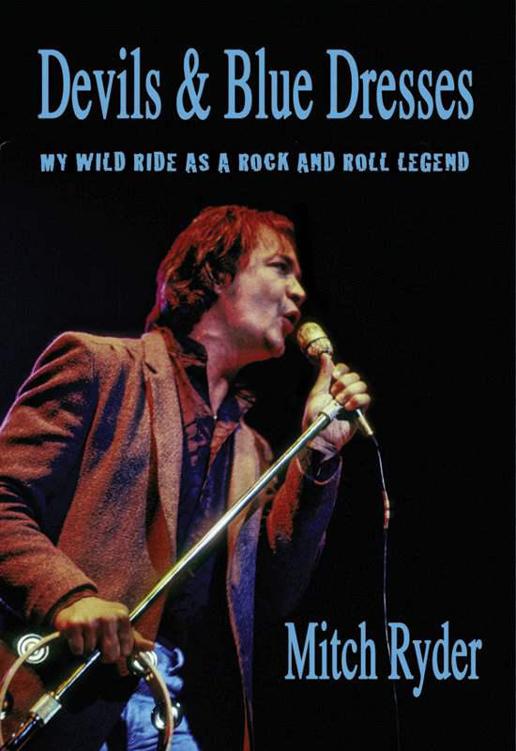

Devils & Blue Dresses: My Wild Ride as a Rock and Roll Legend

tell you they were models.

But the real uncut jewel at

Creem

lay hidden in the walls of the building at Cass and, if the wind was right, you could here him cursing his Viking gods for abandoninghim to the presence of a certain evil force named Mitch Ryder. His name was Dave Marsh, and he was

Creem’s

head music critic/music editor/spiritual guide.

I’ve always wondered about critics. I mean, what causes them to be born? What was their childhood like? When all the little boys and girls were playing out their fantasies and dreams of what they wanted to be when they grew up how could you spot the ones who wanted to be critics? Did they say to themselves, “I want to pass judgment on something and I’m going to make it something I most likely will not know shit about,” or did they simply come out of the womb complaining? Were they picked on excessively? Were they nerds? And most puzzling is the question of historian impotence. Is an historian, in this case music historian, the kid who collected the most records? Is that how they qualified themselves? I suspect that in most cases budding critics envied beyond reason the power of those who could accomplish that which they could never summon the courage to attempt. I also enjoy the notion that music critics believe they somehow protect the public.

Back to Dave. He was born in Michigan and had taken massive amounts of LSD so as to be rejected by the draft and the army during the Vietnam War. His flashbacks scared him enough to seek the truth so badly that he ended up a fucking genius. Brain damaged or not, the guy could write and his written critiques, buoyed by flashbacks, would scatter so many elements of his subject’s music that the law of averages could only produce the truth about the artist.

Dave Marsh was taller than Barry but smaller than me and he spent way too much time trying to figure out how to kick my ass. He was fun to watch, all skinny with his long, stringy, drowned rat-like hair, and I looked forward with great anticipation to his manic outbursts. One time, after I had put together a band and was taking a break from rehearsal, a great crashing noise was heard and I looked out the window to see broken glass and an innocent typewriter scattered all over the sidewalk and street three stories below. Apparently, the volume of our instruments was interfering with Dave’s ability to concentrate, and so he tossed his typewriter through one of the huge plate glass windows that covered the front of the building.

In his early career there, before he made an international name for himself, his talent was the only reliable fuel that kept everyone at

Creem

warm. Barry wrote as well, and in the future many more good writers would work for

Creem

, but David . . . he was Mark Twain’s cynical, illegitimate, genetic missing link.

Chapter 17

I FOUND MYSELF MISSING S USAN AND D AWN and Joel. One day while she was working at the job she took out of necessity, I went to her house and cleaned the kitchen. I wanted to surprise them with a perfectly ordered and magically cleaned house. I looked around the small home Susan had created and I fell to my knees buried in self-pity and sadness. I wished I was still making good money, but that money was the reason for all our suffering. It was a pitiful exhibition and I obviously didn’t get it at all, but I walked through the small house looking at my children’s toys scattered about the rooms and their little clothes lying about and deep in my heart I still wanted to be a part of that. I picked up the clothes, folded them, and held them to my face. I missed the safety of a family, my family.

I spent the afternoon straightening and cleaning, as if somehow making up for the neglect and irresponsibility I had shown them. It brought back the coldness I had felt as a child and I began crying again and feeling sorry for myself but now, looking back, I clearly see the impact of my own parents’ neglect.

The next time I saw Susan, I begged her to take me back. I had hurt her so deeply she refused; she was not a fool. Maybe too trusting, but certainly not a fool. She knew it was impossible for me to miss something I never had and she set about devoting her life to raising our children.

Susan was not a heartless person and she allowed me to have open visitation, because she knew what my business was like. If I were to spend any time at all with our children, she would have to be as liberal as possible. I had hurt them

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher