![Fatherland]()

Fatherland

walled room for more than three hours, going crazy. Then she had been driven to another building to give a statement to some creepy SS man in a cheap wig, whose office had been more like that of a pathologist than a detective.

March smiled at the description of Fiebes.

She had already made up her mind not to tell the Polizei about Stuckart's call on Saturday night, for an obvious reason. If she had hinted that she had been preparing to help Stuckart defect, she would have been accused of "activities incompatible with her status as a journalist" and arrested. As it was, they had decided to deport her anyway. So it goes.

The authorities were planning a fireworks display in the Tiergarten, to commemorate the Führer's birthday. An area of the park had been fenced off, and pyrotechnicians in blue overalls were laying their surprises, watched by a curious crowd. Mortar tubes, sandbagged emplacements, dugouts, kilometers of cable: they looked more like the preparations for an artillery bombardment than for a celebration. Nobody paid any attention to the SS-Sturmbannführer and the woman in the blue plastic coat.

He scribbled on a page of his notebook.

"These are my telephone numbers—office and home. Also, here are the numbers of a friend of mine called Max Jaeger. If you can't get hold of me, call him." He tore out the page and gave it to her. "If anything suspicious happens, anything worries you—it doesn't matter what the time is—call."

"What about you? What are you going to do?"

"I'm going to try to get to Zürich tonight. Check out this bank account first thing tomorrow."

He knew what she would say even before she opened her mouth.

"I'll come with you."

"You'll be much safer here."

"But it's my story, too."

She sounded like a spoiled child. "It's not a story, for God's sake." He bit back his anger. "Look. A deal. Whatever I find out, I swear I'll tell you. You can have it all."

"It's not as good as being there."

"It's better than being dead."

"They wouldn't do anything like that abroad."

"On the contrary, that's exactly where they would do it. If something happens here, they're responsible. If something happens abroad ..." He shrugged. "Prove it."

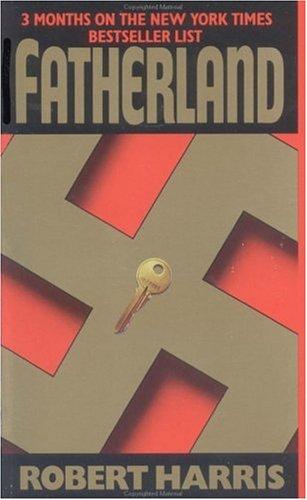

They parted in the center of the Tiergarten. He strode briskly across the grass, toward the humming city. As he walked, he took the envelope out of his pocket, squeezed it to check that the key was still in it and—on impulse— raised it to his nose. Her scent. He looked back over his shoulder. She was walking through the trees with her back to him. She disappeared for a moment, then reappeared; disappeared, reappeared—a tiny, birdlike figure—bright blue plumage against the dreary wood.

5

The door to March's apartment hung off its hinges like a broken jaw. He stood on the landing, listening, his pistol drawn. The place was silent, deserted.

Like Charlotte Maguire's, his apartment had been searched, but by hands of greater malevolence. Everything had been tipped into a heap in the center of the living room—clothes and books, shoes and old letters, photographs and crockery and furniture—the detritus of a life. It was as if someone had intended to make a bonfire but had been distracted at the last minute, before he could apply the torch.

Wedged upright on top of the pyre was a wooden- framed photograph of March, age twenty, shaking hands with the commander of the U-Boot Waffe , Admiral Dönitz. Why had it been left like that? What point was being made? He picked it up, carried it over to the window, blew dust off it. He had forgotten he even had it. Dönitz liked to come aboard every boat before it left Wilhelm-shaven: an awesome figure, ramrod straight, iron- gripped, gruff. "Good hunting," he had barked at March. He growled the same to everyone. The picture showed five young crewmen lined up beneath the conning tower to meet him. Rudi Halder was to March's left. The other three had died later that year, trapped in the hull of U-175.

Good hunting.

He tossed the picture back onto the pile.

It had taken time to do all this. Time and anger and the certainty of not being disturbed. It must have happened while he was under guard in Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. It could only have been the work of the Gestapo. He remembered a line of graffiti scrawled by the White Rose on a wall near Werderscher-Markt: "A police state is a country run by criminals."

They had opened his mail. A couple of bills, long overdue—they were welcome to them—and a letter

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher