![Fool (english)]()

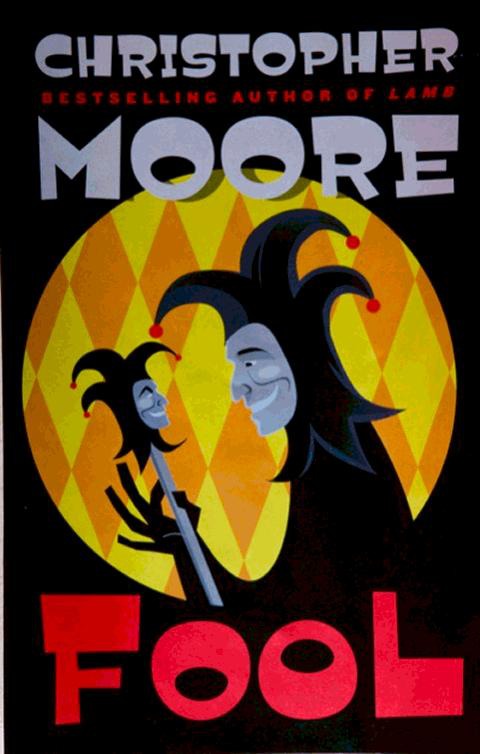

Fool (english)

were long from being established, and at best, Leir would have been some sort of a tribal leader, not the sovereign of a vast kingdom with authority over a complex sociopolitical system of dukes, earls, and knights. A mud fortress would have been his castle. In the play, Shakespeare makes references to Greek gods, and indeed, legend says that Leir’s father, Bladud, who was a swineherd, a leper, and king of the Britons, journeyed to Athens looking for spiritual guidance, and returned to build a temple to the goddess Athena at Bath, where he worshipped and practiced necromancy. Leir became king rather by default when Bladud’s essential bits dropped off. The battle for souls between the Christians and the pagans that I portray in Fool probably took place closer to around A.D. 500 to 800, rather than during Pocket’s imagined thirteenth century.

Time, then, becomes a bit of a problem, not just in relation to history, but to language as well. (The time frame of the play seemed to bollocks up even Shakespeare, for at one point he has the fool rattle off a long list of prophecies, after which he says, “This prophecy Merlin shall make; for I live before his time” (Act III, Scene 2). It’s as if Will threw his quill in the air and said, “I know not what the hell is going on, therefore I shall cast this beefy bit of bull toss to the groundlings and see if it slides by.” No one appears to know what kind of language they were speaking in 400 B.C., but it certainly wasn’t English. And while Shakespeare’s English is elegant and in many ways revolutionary, much of it is foreign to the modern English reader. So, in the tradition of Will throwing his quill into the air, I decided to set the story in a more or less mythical Middle Ages, but with the linguistic vestiges of Elizabethan times, modern British slang, Cockney slang (although rhyming slang remains a complete mystery to me), and my own innate American balderdash. (Thus Pocket refers to the quality of Regan’s gadonkage and Thalia refers to St. Cinnamon driving the Mazdas out of Swinden-with full historical immunity.) And for those sticklers who will want to point out the anachronisms in Fool, rest easy, the whole book is an anachronism. Obviously. There are even references to the “Mericans” as a long extinct race, which places our own time somewhere in the distant past. (“Long ago in a galaxy far away,” if you get my meaning.) It was designed thus.

In dealing with the geography of the play, I looked for the modern locations that are mentioned in its text: Gloucester, Cornwall, Dover, etc. The only Albany I could find is now, more or less, within the London metropolitan area, so I set Goneril’s Albany in Scotland, mainly to facilitate easy access to Great Birnam Wood and the witches from Macbeth. Dog Snogging, Bongwater Crash, and Bonking Ewe on Worms Head and other towns are located in my imagination, except that there really is a spot called Worms Head in Wales.

The plot for Shakespeare’s play King Lear was lifted from a play that was produced in London perhaps ten years earlier, called The Tragedy of King Leir, the printed version of which has been lost. King Leir was performed in Shakespeare’s time, and there is no way of knowing what the text was, but the story line was similar to the Bard’s play and it’s fairly safe to say he was aware of it. This was not unusual for Shakespeare. In fact, of his thirty-eight plays, it’s thought that only three sprang from ideas original to Shakespeare.

Even the text of King Lear that we know was pieced together by Alexander Pope in 1724 from bits and pieces of previously printed versions. Interestingly enough, in contrast to the tragedy, England’s first poet laureate, Nathan Tate, rewrote King Lear with a happy ending, wherein Lear and Cordelia are reunited, and Cordelia marries Edgar and lives happily ever after. Tate’s “happy ending” version was performed for nearly two hundred years before Pope’s version was revived for the stage. And Monmouth’s Kings of Britain indeed shows Cordelia as becoming queen after Leir, and reigning for five years. (Although, again, there is no historical record to support this.)

A few who have read Fool have expressed a desire to go back and read Lear, to perhaps compare the source material with my version of the story. (“I don’t remember the tree-shagging parts in Lear, but it has been a long time.”) While you could certainly find worse ways to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher