![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

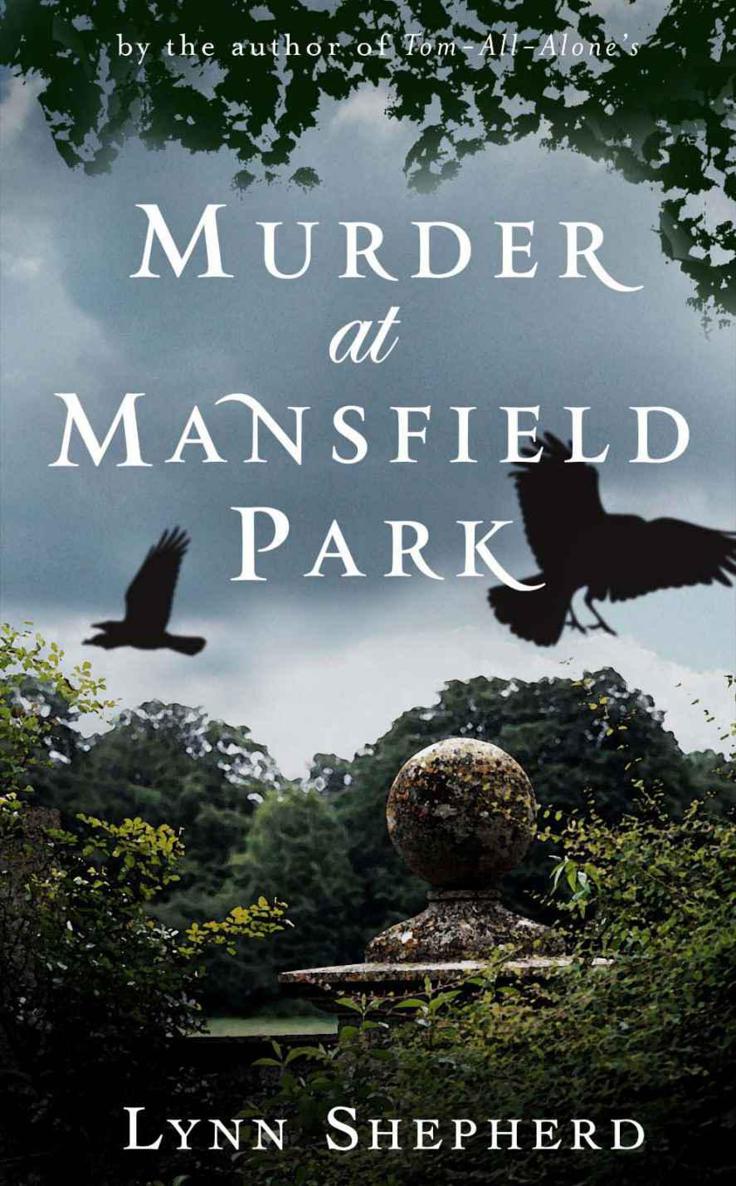

Murder at Mansfield Park

Bertram’s chamber, and try if she might be permitted to see her. To judge from Rogers’s words the preceding day, Julia might even have

recovered sufficiently to rise from her bed. Mary made her way down the corridor, hearing the sounds of the mansion all around her; the tapping of servants’ footsteps and the murmur of voices

were all magnified in a quite different way from what she was accustomed to, in the small rooms and confined spaces of the parsonage. A few minutes later she saw a woman emerging from a door some

yards ahead of her, carrying a tray; it was Chapman, Lady Bertram’s maid. The woman hastened away without seeing her, and Mary moved forwards hesitatingly, not wishing to appear to intrude.

As she drew level with the door she noticed that it was still ajar, and her eyes were drawn, almost against her will, to what was visible in the room.

It was immediately apparent that this was not Lady Bertram’s chamber, but her daughter’s; Maria Bertram was still in bed, and her mother was sitting beside her in her dressing gown.

Mary had not seen either lady for more than a week, and the change in both was awful to witness. Lady Bertram seemed to have aged ten years in as many days; her face was grey, and the hair escaping

from under her cap shewed streaks of white. Maria’s transformation was not so much in her looks as in her manner; the young woman who had been so arch and knowing when Mary last conversed

with her, was lying prostrate on the bed, her handkerchief over her face, and her body racked with muted sobs. Lady Bertram was stroking her daughter’s hair, but she seemed not to know what

else to do, and the two of them formed a complete picture of silent woe. Mary had no difficulty in comprehending Lady Bertram’s anguish—she had supplied a mother’s place to Fanny

Price for many years, and the grief of her death had now been superadded to the public scandal of her disappearance; Maria’s condition was more perplexing. Some remorse and regret she might

be supposed to feel at Fanny’s sudden and unexpected demise, but this utter prostration seemed excessive, and out of all proportion, considering their recent enmity.

Mary was still pondering such thoughts when she became aware of a third person in the room: Mrs Norris was standing at the foot of the bed, observing the two women almost as intently as Mary

herself. A slight movement alerting that lady to Mary’s presence, she moved at once towards the door with all her wonted vigour and briskness.

‘I do not know why it was necessary for Miss Crawford to remain in the house last night,’ she said angrily, to no-one in particular. ‘She seemed perfectly recovered to me, and

in my opinion it is quite intolerable to have such an unnecessary addition to our domestic circle at such a time. But I did, at the very least , presume we would be not be subjected to vulgar and intrusive prying .’

‘Sister, sister,’ began Lady Bertram, in a voice weakened by weeping, but Mrs Norris did not heed her, and seized the handle of the door, with an expression of the utmost

contempt.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Mary. ‘I did not mean—I was looking for Miss Julia’s chamber—’

‘I doubt she wishes to see you, any more than we do. Be so good as to leave the house at your earliest convenience. Good morning, Miss Crawford.’

And the door slammed shut against her.

Mary took a step backward, hardly knowing what she did, and found herself face to face with one of the footmen; he, like Mrs Chapman, was already dressed in mourning clothes.

‘I am sorry,’ stammered Mary, her face colouring as she wondered how much of Mrs Norris’s invective had been overheard, ‘I did not see you.’

‘That’s quite all right, miss,’ he replied, his eyes fixed on the carpet.

‘I was hoping to find Miss Julia’s room. Perhaps you would be so good as to direct me?’

‘’Tis at farther end of t’other wing, miss. By the old school-room.’

‘Thank you.’

The footman bowed and hurried away in the opposite direction, without meeting her eye, and Mary stood for a moment to collect herself, and still her swelling heart, before continuing on her way

with a more purposeful step.

Nearing the great staircase, she became aware of voices in the hall below, and as she came out onto the landing, she was able to identify them, even though the speakers were hidden from her view

by a curve in the stairs. It was Edmund, and Tom

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher