![Red Bones (Shetland Quartet 3)]()

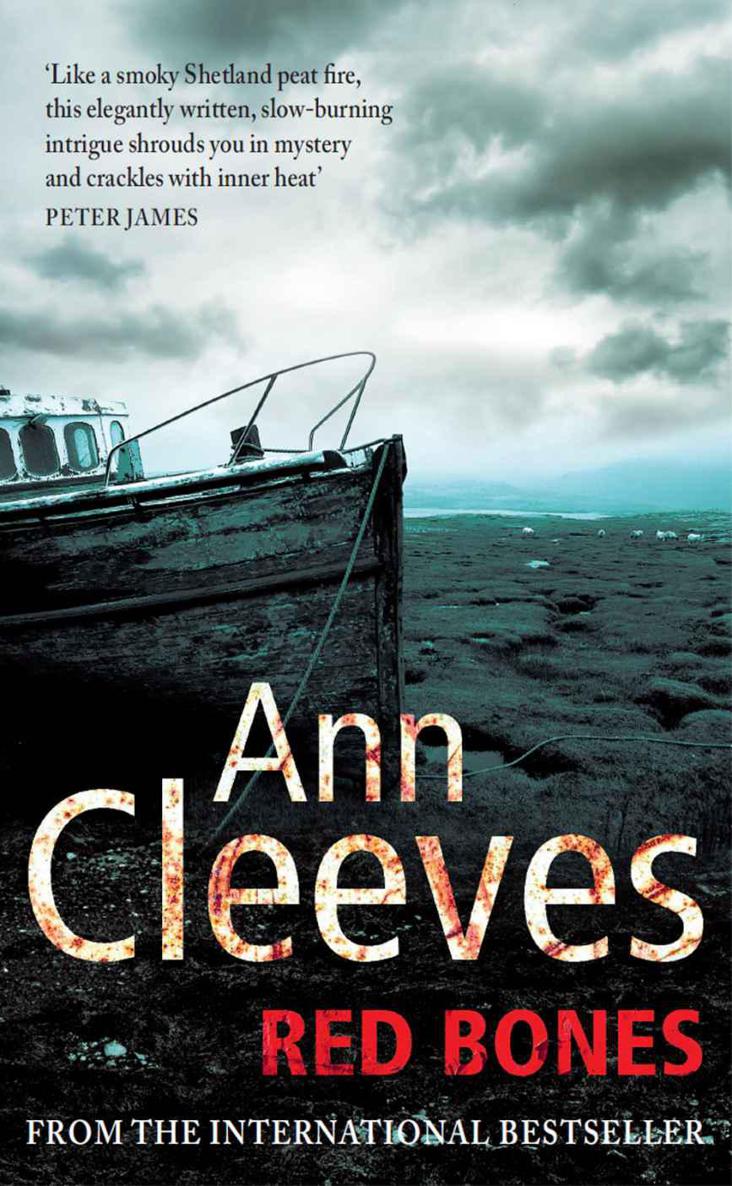

Red Bones (Shetland Quartet 3)

had spread ahead of her, full of possibilities.

Mima had realized how happy she was. Two nights before she’d been shot, she’d called Hattie into the house. She’d poured glasses of whisky, put them on a tray with the bottle and a little jug of water. It had been unusually mild and they’d sat outside on the bench made of driftwood that stood by the kitchen door, the tray on the ground between them.

‘Now what has happened to you over the winter? You look like the cat that got the cream.’

‘Nothing’s happened. I’m just pleased to be back in the island. You know how much I like it here. It’s the only place I feel quite sane. It’s the best place in the whole world.’

‘Maybe it is.’ Mima had gathered her cat on to her lap and given a little laugh. ‘But what would I know? I’ve never lived anywhere else. But maybe it would be good to see a bit of the world before I die. Perhaps you’ll dig up a hoard of treasure in my land and I’ll be able to travel like the young ones do.’

Then she’d looked at Hattie with her bright black eyes, quite serious. ‘And it’s not so perfect here, you ken. Bad things happen here the same as everywhere else. Terrible things have happened here.’

Hattie had taken another drink of the whisky, which she thought tasted of peat fires. ‘I can’t believe that. What are you talking about?’

She’d expected gossip. Mima was a great gossip. She thought there’d be a list of the usual island sins – adultery, greed and the foolishness of bored young men. But Mima hadn’t answered directly at all. Instead she’d gone on to talk about her own youth. ‘I got married straight after the war,’ she said. ‘I was far too young. But my man worked with the men of the Shetland Bus and we got used to seeing them taking risks. You’ll have heard about the Shetland Bus?’

Hattie shook her head. She was dazed now by the whisky, the low spring sun in her eyes.

‘It was after the Germans had invaded Norway. Small fishing boats were used to carry agents in and bring folk out. They called that the Bus. It was run from the big house in Lunna. There were a few Whalsay men who helped and they got close to the Norwegian sailors. I’m never sure exactly what happened. Jerry never liked to speak about it and he wasn’t quite the same afterwards . . .’ She stared into the distance. ‘We were all crazy then.’

Hattie had thought Mima was going to explain, but she had wrapped her arms around the cat, poured herself another dram and laughed. ‘Certainly more mad than dee!’

‘I hope it didn’t upset you too much to see the skull in the practice trench.’ Hattie had remembered Mima’s white face, the way she’d fled into the house. ‘It’s not that unusual, you know. Old bones turning up at a dig. I suppose we’re used to it and we’re not squeamish any more.’

‘I’m not squeamish!’ Mima’s voice had been almost brutal. ‘It was a shock, that was all.’ Hattie hoped she was going to explain further, but the old woman pushed the cat from her lap and stood up. It was clear Mima was ready for her to go: ‘You’ll have to excuse me. There’s a phone call I must make.’ And Mima had stomped into the house without saying goodbye. Hattie had heard her voice through the open door. It sounded angry and loud.

Now Mima was dead and Hattie would never find out what had so disturbed her. Setter felt quite different without Mima there. Even from outside it was different. Before, they’d have heard the radio, Mima singing along or shouting at it if she disagreed with one of the speakers. Sophie saw Sandy through the window as they were walking past and it was her idea to go in.

‘Come on,’ Sophie said in her loud, confident, public-schoolgirl voice. ‘We’d better go in and tell him we’re here. Besides, he might have the kettle on.’ They hadn’t seen Joseph at that point and could hardly turn round and go out again when they realized Mima’s son was there.

Then Hattie had brought up the matter of the dig. So eager to please, so apologetic, the words had tumbled out. And Joseph had frowned and refused to give any sort of commitment about the future of the project. At least that was how it had seemed to her. She thought she might be banished from Shetland and never allowed back. Why didn’t I keep my mouth shut? she thought. Why didn’t we just sneak past the house and go on with our work?

After Sandy’s phone had rung he and his father

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher