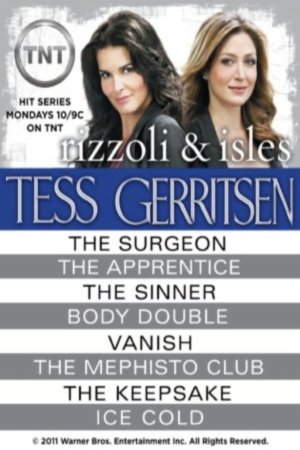

![Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set]()

Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set

me. The Rohypnol. Every so often, I’ll have a flashback. Something that may or may not be real.”

“And you still have these flashbacks?”

“I had one last night. It was the first one in months. I thought I was over them. I thought they’d gone away.” She walked to the window and stared out. It was a view darkened by the shadow of towering concrete. Her office faced the hospital, and one could see row upon row of patients’ windows. A glimpse into the private worlds of the sick and dying.

“Two years seems like a long time,” she said. “Time enough to forget. But really, two years is nothing.

Nothing.

After that night, I couldn’t go back to my own house. I couldn’t set foot in the place where it happened. My father had to pack up my things and move me into a new place. There I was, the chief resident, accustomed to the sight of blood and guts. Yet just the thought of walking up that hallway, and opening my old bedroom door—it made me break out in a cold sweat. My father tried to understand, but he’s an old military man. He doesn’t accept weakness. He thinks of it as just another war wound, something that heals, and then you get on with your life. He told me to grow up and get over it.” She shook her head and laughed. “

Get over it.

It sounds like such an easy thing. He had no idea how hard it was for me just to step outside every morning. To walk to my car. To be so exposed. After a while, I just stopped talking to him, because I knew he was disgusted by my weakness. I haven’t called him in months.…

“It’s taken me two years to finally get my fear under control. To live a reasonably normal life where I don’t feel as if something’s going to jump out from every bush. I had my life back.” She brushed her hand across her eyes, a swift and angry swipe at her tears. Her voice dropped to a whisper. “And now I’ve lost it again.…”

She was shaking with the effort not to cry, hugging herself, her fingers digging into her own arms as she fought for control. He rose from the chair and crossed to her. Stood behind her, wondering what would happen if he touched her. Would she pull away? Would the mere contact of a man’s hand repulse her? He watched helplessly as she curled into herself, and he thought she might shatter before his eyes.

Gently he touched her shoulder. She didn’t flinch, didn’t pull away. He turned her toward him, his arms encircling her, and drew her against his chest. The depth of her pain shocked him. He could feel her whole body vibrating with it, the way a storm batters a swaying bridge. Though she made no sound, he felt the shaky intake of her breath, the stifled sobs. He pressed his lips to her hair. He could not help himself; her need spoke to something deep inside him. He cupped her face in his hands and kissed her forehead, her brow.

She went very still in his arms, and he thought: I’ve crossed the line. Quickly he released her. “I’m sorry,” he said. “That should not have happened.”

“No. It shouldn’t have.”

“Can you forget it did?”

“Can you?” she asked softly.

“Yes.” He straightened. And said it again, more firmly, as though to convince himself. “Yes.”

She looked down at his hand, and he knew what she was focusing on. His wedding ring. “I hope for your wife’s sake that you can,” she said. Her comment was meant to instill guilt, and it did.

He regarded his ring, a simple gold band that he had worn so long it seemed grafted to his flesh. “Her name was Mary,” he said. He knew what Catherine had assumed: that he was betraying his wife. Now he felt almost desperate to explain, to redeem himself in her eyes.

“It happened two years ago. A hemorrhage into her brain. It didn’t kill her, not right away. For six months, I kept hoping, waiting for her to wake up.…” He shook his head. “A chronic vegetative state was what the doctors called it. God, I hated that word,

vegetative

. As if she was a plant or some kind of tree. A mockery of the woman she used to be. By the time she died, I couldn’t recognize her. I couldn’t see anything left of Mary.”

Her touch took him by surprise, and he was the one who flinched at the contact. In silence they faced each other in the gray light through the window, and he thought: No kiss, no embrace, could bring two people any closer than we are right now. The most intimate emotion two people can share is neither love nor desire but pain.

The buzz of the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher