![Secret Prey]()

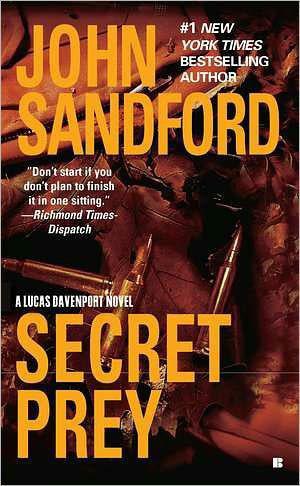

Secret Prey

settled.’’

Five forty-five in the morning, opening day of deer season. O’Dell led the way off the porch, the chairman of the board at her shoulder, the other three men trailing behind.

Terrance Robles was the youngest of them, still in his mid-thirties. He was a blocky man with thick, blackrimmed glasses and a thin, curly beard. His watery blue eyes showed a nervous flash, and he laughed too often, a shallow, uncertain chuckle. He carried a stainless Sako .270, mounted with a satin-finished Nikon scope. Robles had little regard for tradition: everything he hunted with was new technology.

James T. Bone might have been Susan O’Dell’s brother: forty, as she was, Bone was slim, tanned, and dark-eyed, his face showing a hint of humor in a surface that was hard as a nut. He brought up the rear with a .243 Mauser Model 66 cradled in his bent left arm.

Four of the five—the chairman of the board, Robles, O’Dell, and Bone—were serious hunters.

The chairman’s father had been a country banker. They’d had a nice rambling stone-and-redwood home on Blueberry Lake south of Itasca, and his father had been big in Rotary and the Legion. The deer hunt was an annual ritual: the chairman of the board had hung twenty-plus bucks in his forty-six years: real men didn’t kill does.

Robles had come to hunting as an adult, joining an elk hunt as a thirtieth-birthday goof, only to be overwhelmed by its emotional power. For the past five years he’d hunted a half-dozen times annually, from Alaska to New Zealand.

O’Dell was a rancher’s daughter. Her father owned twenty miles of South Dakota just east of the Wyoming line, and she’d joined the annual antelope hunt when she was eight. During her college years at Smith, when the other girls had gone to Ivy League football games with their beaux, she’d flown home for the shooting.

Bone was from Mississippi. He’d learned to hunt as a child, because he wanted to eat. Once, when he was nine, he’d made soup for himself and his mother out of three carefully shot blackbirds.

Only McDonald disdained the hunt. He’d shot deer in the past—he was a Minnesota male, and males of a certain class were expected to do that—but he considered the hunt a pain in the ass. If he killed a deer, he’d have to gut it. Then he’d smell bad and get blood on his clothing. Then he’d have to do something with the meat. A wasted day. At the club, they’d be playing some serious gin—drinking some serious gin, he thought—and here he was, about to climb a goddamned tree.

‘‘Goddamnit,’’ he said aloud.

‘‘What?’’ The chairman grunted, turned to look at him.

‘‘Nothing. Stray thought,’’ McDonald said.

One benefit: If you killed a deer, people at the club attributed to you a certain common touch—not commonness, which would be a problem, but contact with the earth, which some of them perceived as a virtue. That was worth something; not enough to actually be out here, but something.

THE SCENT OF WOODSMOKE HUNG AROUND THE cabin, but gave way to the pungent odor of burr oaks as they pushed out into the trees. Fifty yards from the cabin, as they moved out of range of the house lights, O’Dell switched on her headlamp, and the chairman turned on a hand flash. Dawn was forty-five minutes away, but the moonless sky was clear, and they could see a long thread of stars above the trail: the Dipper pointing down to the North Star.

‘‘Great night,’’ Bone said, his face turned to the sky.

A small lake lay just downslope from the cabin like a smoked mirror. They followed a shoreline trail for a hundred and fifty yards, moved single file up a ridge, and continued on, still parallel to the lake.

‘‘Don’t step in the shit,’’ the woman said, her voice a snapping break in the silence. She caught a pile of fresh deer droppings with her headlamp, like a handful of purple chicken hearts.

‘‘We did that last week with the Cove Links deal,’’ the chairman said dryly.

The ridge separated the lake and a tamarack swamp. Fifty yards further on, Robles said, ‘‘I guess this is me,’’ and turned off to the left toward the swamp. As he broke away from the group, he switched on his flash, said, ‘‘Good luck, guys,’’ and disappeared down a narrow trail toward his tree stand.

The chairman of the board was next. Another path broke to the left, toward the swamp, and he took it, saying, ‘‘See you.’’

‘‘Get the buck,’’ said O’Dell,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher