![The Crowded Grave]()

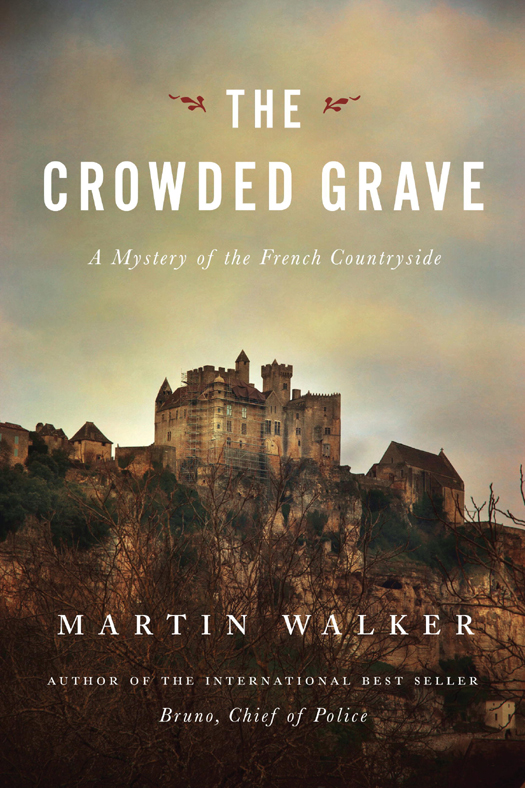

The Crowded Grave

town,” said Bruno. “That’s what brought me here.”

“Crazy birds,” said Louis, grimacing in rueful affection. “They’ve got a perfectly good pond back in the field, but give them a sniff of someplace new and off they go.” He gestured back beyond his house where already some of the ducks, frustrated at their efforts to escape through the newly sealedbarrier, were splashing and paddling serenely in their old familiar pond.

A young boy of about ten labored toward them from the woods, proudly hauling a section of wire fence.

“I found it, Papa,” he shouted. “And there’s more. I can show you where.” His face broke into a grin at seeing Bruno, who taught him to play rugby in winter and tennis in summer. “Bonjour, Monsieur Bruno.” He dropped the fence and came forward to shake hands.

“Bonjour, Daniel. Did you see or hear anything when this happened?”

“Nothing. The first I heard was when Papa woke us all up to come out and save the birds.”

“I heard something, a duck call, a single one and then repeated, just before the cockerel started,” said Louis. “So it must have been a bit before dawn. I remember thinking that’s odd, because the ducks don’t usually stir until after the hens.”

“Could it have been a lure, one of those hunter’s calls?” Bruno asked. “Whoever cut the fence must have had some way to wake the birds and tempt them to move. They’d have wanted them out before you and the family were awake.”

“It must have been something like that,” Sandrine said. “The birds tend to stick around the barn, waiting to be fed. They’ve never gone off before, even when we had that storm that knocked part of the fence down.”

“I’d better get back to the road and see that jam is cleared,” said Bruno.

“Before you go, what do you know about this PETA?” asked Sandrine.

“Not a lot, but I’ll find out,” Bruno replied. “I think you’ve lost one or two birds to the cars, but not many.”

“Those birds are worth six euros each to us,” said Sandrine. “We can’t afford to lose any of them, what with the bank loanwe have to pay until we sell this lot. What if those PETA people come again?”

“I’ll shoot the bastards,” Louis said. “We’ll take turns keeping watch, sit up all night if we have to.”

“You have a right to protect your property with reasonable force, according to the law,” said Bruno. “But people interpret ‘reasonable force’ in different ways. If you hear anything happening again, it’s best you call me. Whatever you do, don’t use a firearm or any kind of weapon. The best thing is to photograph them so we can identify who they are. If you have any lights you can rig up, or one of those motion detectors …”

“A camera won’t do any good,” said Alain. “Even with photos the damn courts will take their side. They’re all mad Greenies, the magistrates. Then there’s those food inspectors and all the other rules and regulations, tying us up in knots.”

“I think I know who it is,” said Sandrine. “It’s those students at the archaeology site who came in last week, working on some dig with that German professor, over toward Campagne. They’re all staying at the municipal campground. This time of year, they’re the only strangers around here and you know what those students are like. They’re all Greens now.”

Bruno nodded. “I’ll check it out. See you later.” Along the fence he saw the fluttering of another of the leaflets inside a plastic bag, one of the kind that could be sealed and used in freezers. He took out a handkerchief and gingerly removed the pins that held it to the wire. Forensics might get something from it. There were several more attached along the fence and he took another. He nodded at Alain. “Do you want to come with me? You’ll have to move your tractor.”

As he reached the road, where the jam was steadily clearing itself, Bruno’s phone rang again. He checked the screen, saw the name “Horst,” and this time he answered. Horst Vogelstern was the German professor of archaeology in charge ofthe student volunteers at the dig. For more than twenty years Horst had spent his vacations at a small house he owned on the outskirts of St. Denis. He ran digs in the Vézère Valley that the local tourist board liked to proclaim as the cradle of prehistoric man. The first site of Cro-Magnon man had been found in the valley over a hundred years earlier, and the famous cave

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher