![The Lesson of Her Death]()

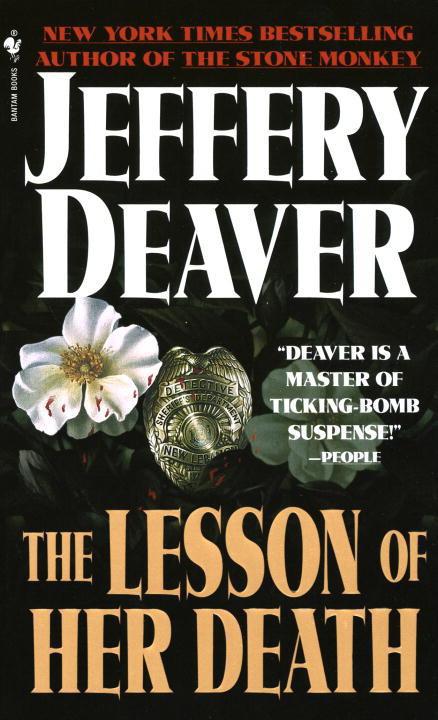

The Lesson of Her Death

Associate Dean Randolph Rutherford Sayles is pierced with a despair as sharp as any triangular musket bayonet. He sits where he has sat for the past three hours, smoking his thirteenth cigarette of the afternoon, in the Holiday Inn on the Business Loop with four Auden University trustees from the East Coast. Their transcripts he is not familiar with, but this he has finally concluded about them: They are men who view Auden as a trade school. Two are lawyers, one is the director of a large nonprofit philanthropic organization and one is a doctor. Their interestin the school derives from the Poli Sci Department, the business school, the Biology Department.

They never glean of course that Sayles holds them in patient contempt for their philistine perspective on education. He can’t afford for them to catch on; either personally or through their fund-raising efforts these four are responsible for close to eleven million dollars a year of funding for the school. Sayles the history professor thinks they are rich fools; Sayles the associate dean of financial aid, immersed presently in hot fucking water, charms them effusively as they indulge in dishes of bad fruit salad in the Riverside dining room.

Occasionally they seem to grow tired of Professor Sayles and their eyes dip toward a five-page document, which the professor prepared earlier in the day and which he views the way FAA inspectors might study the jagged remains of a 747.

“Gentlemen, Auden University is a qualifying not-for-profit corporation, which exempts the institution under the Internal Revenue Code Section 503(c) from paying federal income tax and from a parallel section in the state revenue code from paying state tax. Being a not-for-profit corporation, however, does not mean that it can lose money with impunity.” Ha ha ha. He catches each of their eyes seriatim. “So while the terms red and black don’t have the same meaning they might for, say, G.M., or IBM, we are seriously considering changing the school’s colors from black and gold to crimson.…”

He is passionate and funny, teasing his audience in the manner of a toastmaster, a serendipitous skill he has learned from years of lecturing to twenty-year-olds with attitudes. Yet these Easterners are immune and actually seem embarrassed for Sayles. One says, “We’ve got to start thinking more global on this. Let’s start a law school or hang some balls on the M.B.A. program. Move up into the Wharton frame of mind.”

“Hmm. High capital expense for that,” Sayles offers.

Try fifty million minimum

.

“Maybe a noncredit continuing education program?”

Sayles nods gravely, considering.

You stupid prick. Farmers and Kmart checkers aren’t going to pay good money to study Heidegger at night

. “Hmm. Small market for that,” he says.

One trustee, a trim, golf-playing lawyer, who turned down even the fruit cup as too caloric, says, “I don’t think we should be too fast to give up on Section 42(f) aid.” Under the state education law private colleges can qualify for grants if they admit a large number of minority students, regardless of their academic record.

The others gaze at him in puzzlement. At least here Sayles has allies. The lawyer says, “It was just a thought.”

“Three point six million,” Sayles says slowly, and the discussion goes round and round again. Sayles begins to understand something. These men court clients and patients and chief executive officers who routinely write them checks of ten twenty a hundred thousand dollars. They live with streaked-haired, face-lifted wives and are limoed to art museums and restaurants and offices. Aside from semiyearly meetings at Auden, Palm Springs and Aspen, they are never seen west of Amish country. He decides their interest in their alma mater is just that—an

interest

, nothing more. He is sickened by their suggestions, which are paltry and, worse, obvious; they are student responses to the assignment “How to Save Auden University.”

By the time the last dots of syrup have been sucked out of the fruit cups, Randy Sayles senses with a feeling of terrible waste that he is alone in this struggle to keep the school afloat. The school. And his own career. And perhaps his freedom.

The Easterners promise to keep their thinking caps on. They promise to increase their personal pledges. They promise to mount a campaign among their peers in the East. Then they shake Sayles’s hand and climb intothe limo

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher