![The Lesson of Her Death]()

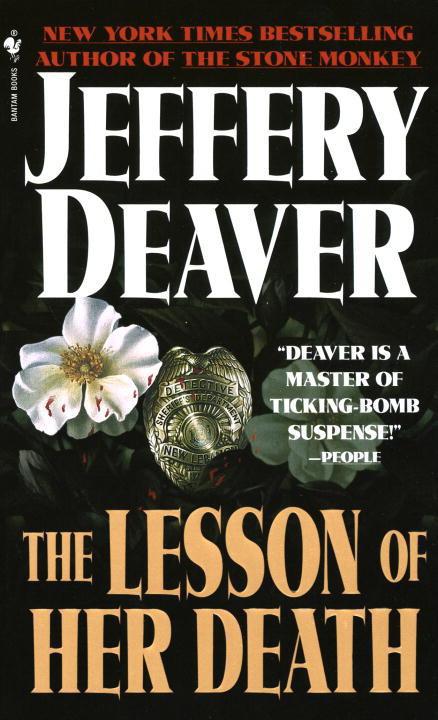

The Lesson of Her Death

and Rossiter cases.”

It took several seconds for the fire to burn across Corde’s cheek. “The county.”

“T.T.’s going to be heading her up.”

“Well, Steve, legally, I suppose, the county can take over any murder investigation it wants to. But the point is it’s never—”

“Bill.”

“The point is it’s never happened before. All right. I’m a little angry. That’s what you’re hearing. I don’t think we’ve done anything to make Ellison feel this way.”

“It was that situation at the dorm.”

“What

situation?”

Ribbon surveyed the rocket pencil’s crash site. “They think you burned her letters and her diary, Bill.”

Corde said nothing.

“They’re thinking it was curious you flew to St. Louis so fast after the killing. When you didn’t find anything there you went to her dorm room and took them and burned it all up. Don’t look that way, Bill. They think you were trying to cover up something between you and her. There’ll be an inquest next month and you’re off the case till it’s over.”

W ynton Kresge’s great-great-great-grandfather, whose name was Charles Monroe, had been a slave, one of two, on a small farm near Fort Henry, Tennessee. The story goes that when the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on New Year’s Day in 1863 Monroe went to his master and said, “I am sorry to tell you this, Mr. Walker, but there is a new law that says you can’t own slaves anymore, including us.”

Walker said, “They did that in Nashville?”

Monroe answered, “No, sir, they did that in the capital, that is to say, Washington, D.C.”

“Blazes,” Walker said, and added that he’d have to look into it. Because both he and his wife were illiterate they had to ask someone to tell them more about this law. Their charming innocence was demonstrated by their choice of Abigail, the Walker’s second slave, to confirm the news. She did so by reading from an outspoken abolitionist penny sheet, which printed the text ofthe Proclamation while avoiding an inconvenient discussion of Lincoln’s jurisdiction to free slaves located in the Confederacy.

“Damnation, he’s right,” Walker said. Then he wished Monroe luck and said by any chance you be interested in staying on for pay and Monroe said he’d be happy to and they negotiated a wage and room and board and Monroe kept on working on the Walker farm until he married Abigail. The Walkers gave them their wedding and Monroe named his first son Walker.

Family history.

And probably as embellished and half-true as any. But what Wynton Kresge thought was most interesting was how his children responded to the story. His eldest son, Darryl, eighteen, was horrified that he had been descended from slaves and never wanted the fact mentioned. Kresge felt bad the boy was so ashamed and grumbled that since he was black and had grown up in the United States and not on the Ivory Coast, how come that was such a shock?

Kresge’s eldest daughter, Sephana, sixteen, on the other hand often talked about Monroe’s plight. Which was how she referred to it.

Plight

. She hated Monroe for going back to work for Walker. She hated him for not putting a Minié ball in his master’s head and torching the farm. Sephana had posters of Spike Lee and Wesley Snipes on her wall. She was beautiful. Kresge had put all serious talks with his daughter on hold for a few years.

Kresge’s fifth child, named after the ancestor in question, was eight and he loved the story. Charles often wanted to act it out, insisting that Kresge take the role of Mr. Walker, while Charles did an impersonation of someone probably not unlike his namesake. Kresge wondered what his youngest son, Nelson, aged two, would say about their ancestor when he learned the story.

These were the thoughts that kept intruding into Kresge’s mind as he sat trying to read in the massive bun-buster swivel chair. He felt all stifled and bouncy with nervous energy so he stood up and walked to thewindow in the far corner of his office. He reached out and rested his hands on the windowsill and did a dozen lazy-boy push-ups then twelve more and twelve more after that until he smelled sweat through his shirt.

The window overlooked not the quad but a strip of commercial New Lebanon, storefronts and flashing trailer signs and a chunk of the satellite dish on the Tavern. He was anxious and his muscles quivered from using them the wrong way, in a soft office, in a soft university, a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher