![The Pure]()

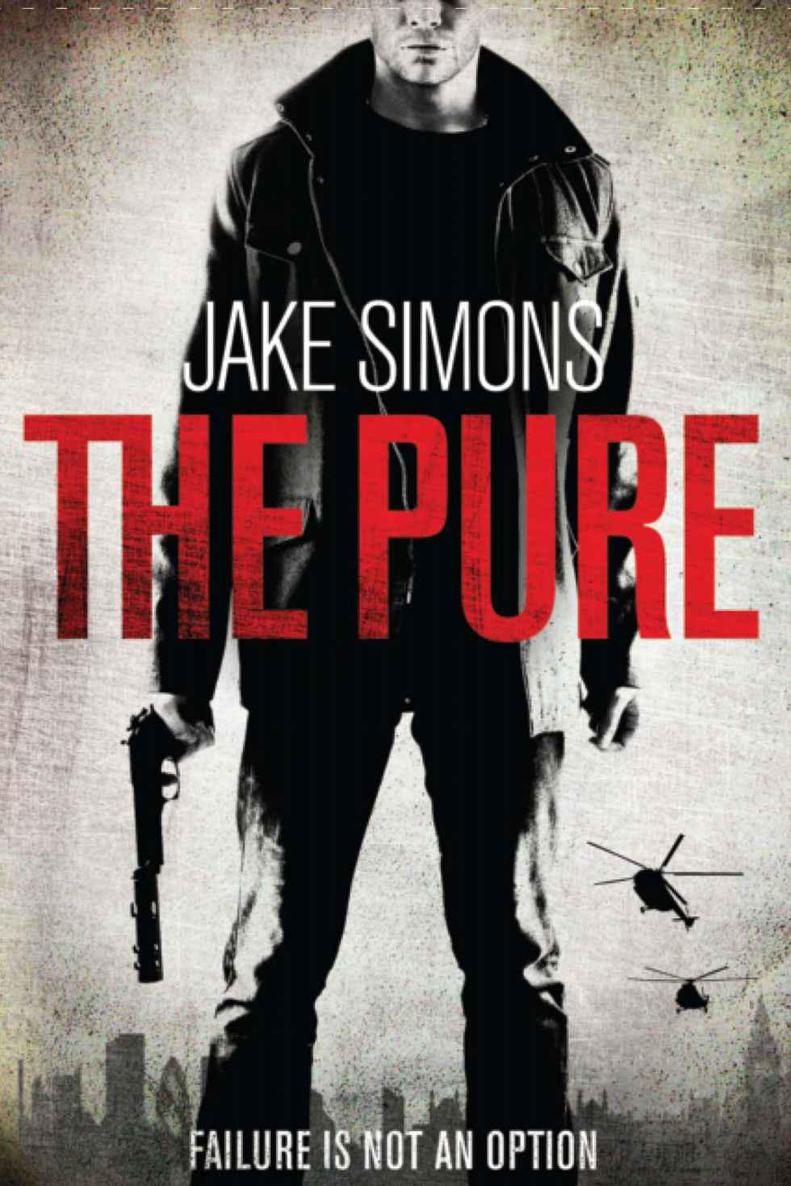

The Pure

he said drily.

‘Look, Daniel. I don’t know what you’re trying to say to me.’

‘Nor do I, kid. But I do know what you’re trying to say to me.’

He went up to the apartment alone and got the dope. With the eighth in his fingers, he crouched on the floor, his eyes screwed tightly shut, dissolving himself into the blackness. Then he rose and stood in front of the bathroom mirror, examining the shadow of bristles across his chin, the lines etched around his mouth, across his forehead, the eyes that could devour the world. He ran the water and splashed his face again and again. Then he checked the cyst on his shoulder. It was sore today. I am starting to forget who I am, he thought. He dried himself with a towel and went downstairs to the street.

‘What took you so long?’ she said.

Without a word, Uzi got into the car and tossed the eighth on to the dashboard. Gal handed him a twenty-pound note and he pocketed it. But he didn’t move.

‘Er, hello?’ said Gal. ‘This is where we go our separate ways.’

‘You said your parents are away in Israel, right?’

‘Yes,’ Gal said slowly.

‘We’ll go to your place, then. Watch a movie or something.’

Gal paused, then smiled, then laughed, then started the engine. ‘You army guys are all the same,’ she said casually. ‘I love it.’ She turned up the music loud.

16

‘Drink?’

‘What have you got?’

‘My dad always has beer in the fridge. And there’s wine in the rack, whisky, gin . . .’

‘One of your dad’s beers would be fine.’

‘OK. Do you want a yellow one or a brown one?’

‘A what?’

‘Look, there are two colours.’

‘Oh. A lager. The yellow one.’

The house, on the outskirts of Golders Green, was just as he had expected. Large, comfortable, lived-in: spacious garden overgrown around the edges, oversized television facing a well-used sofa; half-read magazines, Post-it notes on the mirrors, piles of paperwork and books. He followed Gal up several flights of stairs to the loft extension, which smelled of new carpets. As they walked up the stairs, his face was at the level of her hips.

‘You’re good at that,’ she said as he rolled the spliff. ‘A pro.’

‘Practice,’ he said, and lit up. She opened the skylight and turned on a desk lamp. Her phone rang, and she turned it off. Then she put on some music and lay sideways on the bed. He joined her; their legs touched. He sent smoke rings up to the ceiling.

‘So you’re seventeen,’ he said.

‘How old are you?’

‘A little older.’

‘Old enough to be my father?’

‘A young father perhaps.’

‘Wife?’

‘If I had one, would I be here?’

‘Come on, Daniel. I’m not stupid.’

‘No wife. Not that you have to worry about it.’

They smoked.

‘I think it’s wonderful,’ said Gal, breaking a comfortable silence.

‘What is?’

‘I can see you’re hurting, Daniel. I can see you’ve been through a lot. That’s a sacrifice, you know. You’ve given a part of yourself for your country. Your hurt is a gift to your people. It’s wonderful. I mean it. It’s heroic.’

‘You don’t know anything about me.’

‘I don’t need to. Our land depends on people like you accepting burdens that almost destroy you. I’ll bet lots of your friends gave their lives, but you continue to give. You give till it hurts for your country. People like you are the real heroes, the quiet heroes of our people.’

Uzi tried to laugh but no sound would come. He looked over at the person beside him, her unlined face, her clear eyes looking into his, her lips which could smile forever without losing their joy. She didn’t look real. She sucked on the spliff and little threads of smoke traced the contours of her face. He thought of a word. Then it passed from his mind without a trace. He got up.

In the bathroom, he looked out of the window at the sky. It was dark and starless above, and an orange light from the streetlamps was glowing. Of course he was married, technically at least. You had to be married to be a Katsa. This was one of the most glaring ironies of the organisation. Sex in the Office was free and rampant: secretaries, Katsas, wives of Katsas, agents, technicians, translators, audio specialists. The sexual connections went back and forth, web after web, trophy after trophy. But so long as you were married, it was all right. If you were married, you were less vulnerable to bribes. That was the official line.

He took out his Glock –

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher