![Waiting for Wednesday]()

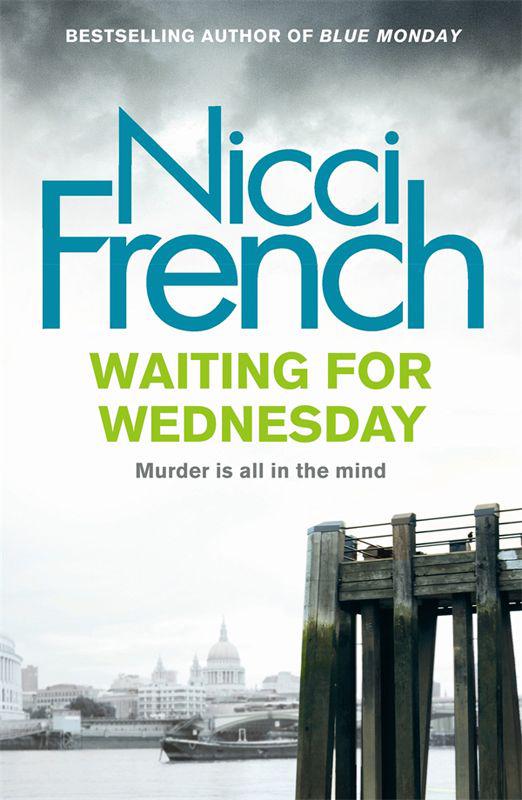

Waiting for Wednesday

long text full of abbreviations she

couldn’t understand. Sasha had left two texts. Judith Lennox had phoned. There

were also several missed calls from Karlsson. When she rang voicemail she heard his

voice, grave and anxious, asking her to get in touch as soon as she got his message. She

stared down at her phone, almost hearing a clamour of voices insisting she get in touch,

scolding her and pleading with her and, worst of all, being in a state of distress about

her. She didn’t have the time for any of that now,

or the energy or the will. Later.

When she eventually reached her house,

letters lay on the doormat and, as she stooped to pick them up, she saw that a couple

had been pushed through the letterbox rather than posted.

One was from Reuben; she recognized his

writing at once. ‘Where the fuck are you, Frieda?’ he wrote. ‘Ring me

NOW.’ He didn’t bother to sign it. The other was from Karlsson, and was more

formal: ‘Dear Frieda, I couldn’t get you onyour phone so

came round on the off-chance. I really would like to see you – as your friend and as

someone who is worried about you.’

Frieda grimaced and pushed both notes into

her bag. She walked into her house. It felt cool and sheltered, almost like she was

walking into a church. It had been so long since she had spent time there alone,

gathering her thoughts, sitting in her study-garret, looking out over the lights of

London, at the centre of the city but not trapped in its feverish rush, its mess and

cruelty. She went from room to room, trying to feel at home again, waiting for a sense

of calm to return to her. She felt that she had passed through a storm and her mind was

still full of the faces she had dreamed about last night, or lain awake thinking of. All

those lost girls.

The flap rattled and the tortoiseshell cat

padded across to her and rubbed its body against her leg, purring. She scratched its

chin and put some more food into its bowl, though Josef had obviously come in to feed

it. She went upstairs, into her gleaming new bathroom, put in the plug and turned on the

taps. She saw her reflection briefly in the mirror: hair damp on her forehead, face pale

and tense. Sometimes she was a stranger to herself. She turned the taps off and pulled

out the plug. She wouldn’t use the bath today. She stepped under the shower

instead, washed her hair, scrubbed her body, clipped her nails, but it was no use. A

thought hissed in her head. Abruptly, she stepped out of the shower, wrapped herself in

a towel, and went into her bedroom. The window was slightly open and the thin curtains

flapped in the breeze. She could hear voices outside, and the hum of traffic.

Her mobile buzzed in her pocket and she

fished it out, meaning to turn it off at once because she wasn’t ready to deal

with the world yet. But it was Karlsson, so she answered.

‘Yes?’

‘Frieda. Thank God. Where are

you?’

‘At home. I’ve just come

in.’

‘You’ve got to get over here

now.’

‘Is it the Lennox case?’

‘No.’ His voice was grim.

‘I’ll tell you when you come.’

‘But –’

‘For once in your life, don’t

ask questions.’

Karlsson met her outside. He was pacing up

and down the pavement, openly smoking a cigarette. Not a good sign.

‘What is it?’

‘I wanted to get to you before bloody

Crawford.’

The commissioner? What on earth –’

‘Is there anything you need to tell

me?’

‘What?’

‘Where were you last night?’

‘I was in Birmingham. Why?’

‘Do you have witnesses to

that?’

‘Yes. But I don’t understand

–’

‘What about your friend, Dr

McGill?’

‘Reuben? I have no idea. What’s

going on?’

‘I’ll tell you what’s

going on.’ He stubbed out his cigarette and lit another. ‘Hal

Bradshaw’s house burned down last night. Someone set it on fire.’

‘

What?

I don’t know

what to say. Was anyone inside?’

‘He was at some conference. His wife

and daughter were there, but they got out.’

‘I didn’t know he had a

family.’

‘Or you wouldn’t have done

it?’ said Karlsson, with a faint smile.

‘That’s a terrible thing to

say.’

‘It surprised me as well. I mean that

someone would marry him, not that someone would burn his house down.’

‘Don’t say that. Not even as a bad

joke. But why have you made me come here to tell me this?’

‘He’s in a bad way, saying wild

things. That it was you – or one of your friends.’

‘That’s ridiculous.’

‘He claims that

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher