![William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue]()

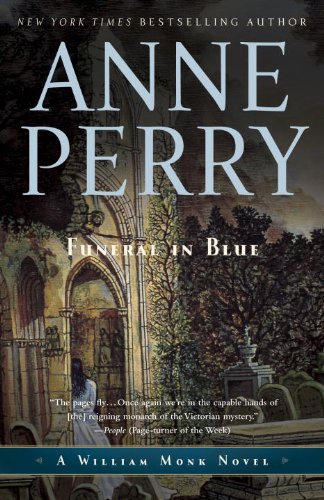

William Monk 12 - Funeral in Blue

Jewish.”

No one moved. There was no sound, and yet the emotion in the room seemed almost to burst at the walls.

“They were both fighters for the revolution,” Monk went on. “Because of her Jewish background, Hanna knew that many families, before the emancipation of the Jews, when they were still forbidden many occupations, excluded from society, denied opportunities and living in constant fear, had changed their Jewish names to German ones. They had taken the Catholic faith, not from conviction but in order to give their children a better life. The Baruch family was one such.” He breathed in deeply. “They changed their name to Beck. Three generations later, the great-grandchildren had no idea they had ever been anything but good Austrian Catholics.”

At last he looked up at Kristian, and saw him start forward, disbelief blank in his face, his eyes wide, aghast, as if the world he knew was disintegrating in his grasp.

“No one knows the conversation between the two women,” Monk went on. “But Elissa was made aware that the man she loved, and had presumed to be of her own people, was actually of her rival’s, although he himself did not know it.” He was aware of faces in the room below him craning around and upward, staring.

“It was necessary to carry dangerous messages to warn other groups of revolutionaries,” Monk said, continuing the story, “in different parts of the city. Hanna was chosen to do it, for her knowledge of the streets of the Jewish quarter and her courage, and perhaps because she was not so closely one of the group, being a Jew. Father Geissner told me that Dr. Beck afterwards felt guilty, even that the ease with which they chose her for the task troubled him. Apparently, he spoke of it outside the confessional as well as within it.”

Mills’s eyes were fixed on him. Not once did he glance away at Pendreigh, or at the judge. “Continue,” he prompted. “What happened to Hanna Jakob?”

“The other group was warned by someone else,” Monk said quietly, aware of how strained his voice was. “And Hanna was betrayed to the authorities. They caught her and tortured her to death. She died alone in an alley, without giving away her compatriots. . . .”

There were gasps in the room. The upturned face of one woman was wet with tears. A voice muttered a prayer.

“By whom was she betrayed?” Mills asked hoarsely.

“Elissa von Leibnitz,” Monk answered. At last he looked at Kristian and saw nightmare in his face. He had not known. No one could look at him and believe that he had.

“No!” Max Niemann struggled to his feet. “No! Not Elissa!” he cried. “It’s not possible!”

Two ushers of the court moved towards him, but he sank back down again before they reached the row of seats where he was. He, too, looked like a man who has seen an abyss open before his feet.

Pendreigh stood with difficulty; only the table in front of him supported his weight. He looked like a pale taper of light with his bloodless face and white wig with thick, golden hair beneath it. His voice came between his teeth hoarsely.

“You lie, sir. I, too, would like to believe that Dr. Beck is innocent, and have done so to this moment. But I will not have you blaspheme the memory of my daughter in order to save him. What you suggest is monstrous, and cannot be true.”

“It is true.” Monk answered him without anger. He could understand the rage, the denial, the unbelievable pain too immense to grasp. “No one thought she meant Hanna to die,” he said softly. “She was certain she would yield up the names long before that point, and would be released, humiliated but uninjured.” He found it difficult to breathe, and to keep control of his face. When he resumed, his voice was harsh with pain. “Perhaps that was the greatest injury of all, the insult. She was betrayed, and yet she died without giving her torturers the names of any of them.”

There was silence, as if every man and woman in the huge room were absorbing the agony into themselves. Even Mills did not move or speak.

Finally, the judge leaned forward. “Are you suggesting, Mr. Monk, that this is relevant to Mrs. Beck’s death?”

Monk turned to him. “Yes, my lord. It is obvious to us here that Dr. Beck is as shattered by this terrible story as Herr Niemann, or indeed Mr. Pendreigh, but there are those in Vienna who were aware of it and could piece together the tragedy, as I did. Surely their existence raises more

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher