![A Lasting Impression]()

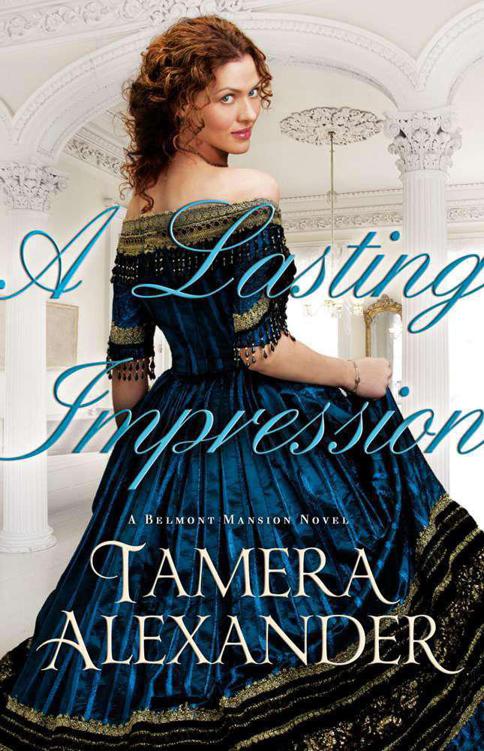

A Lasting Impression

involvement. Does that count for nothing?” She turned to him. “You were there. Their own attorney was present too. Their acceptance of the payment that day indicates willful compliance in the eyes of the law. Does it not, Mr. Monroe?”

Sutton knew he didn’t need to lecture her on the finer points of the law. Adelicia had grown up reading the law books in her father’s library and—according to her late husband, who had been one of the finest attorneys Sutton had known—she began arguing cases with her father at the age of eight. It was a frivolous thought, he knew, but she would have made a formidable lawyer herself.

“Mrs. Acklen, I wish the law were that clear-cut, but we both know it’s not. In a perfect world—”

“Please spare me the perfect-world lecture, Mr. Monroe. In a perfect world justice would always be blind and all verdicts would be just.” She stated it as though she were speaking to a first-year law apprentice.

Sutton bit his tongue, knowing she was upset, and disappointed. Just as he had been when he’d first read the letter. He’d had the luxury of the past three hours to digest the frustration. She’d had the past three minutes. And it was her money they were talking about. Not his. “My apologies, ma’am, if my words seemed trite. That wasn’t my intention. But the fact remains . . .” With deep respect and concern for her, he leveled a stare. “You are an extremely wealthy and well-known widow who played a very deep game during a turbulent time in this country.”

“I was attending to my own affairs, Mr. Monroe. In the manner I thought best.”

“I’m well aware of that. But people haven’t forgotten that you were accused by the Federals of being ‘in complicity with the rebels.’ And the Confederates labeled you a Union woman.”

She scoffed. “You know my goal was to save that cotton. And I went to great lengths—and peril—to do so. Don’t forget my imprisonment! For three days they kept me under house arrest!” She gave an exasperated sigh. “I couldn’t simply stand by and allow three years’ worth of labor and potential revenue to be burned to naught all because of one general’s insatiable thirst for destruction.”

Sutton leaned forward. “Of course, I understand. I was there,” he gently reminded. “Please understand, Mrs. Acklen, I’m not questioning your motives or your actions. I’m only trying to illustrate how I believe the district court viewed this case.”

“I see the argument you’re making, Mr. Monroe. But I fail to see the connection between that and a man who agrees to accept one sum of money for his services, only to later change his mind and sue for a greater sum once he discovers how much money his employer received.” Taking a deep breath, she stood and strode to the window. “The behavior is deceitful and wrong and ought not to be rewarded. Not by a court of law and certainly not by me!”

Weary in body, and of fighting this particular legal battle, Sutton rested his head in his hands, wrestling with how to phrase his next thoughts, but knowing they needed to be said.

Finally, he straightened. “I’ve encouraged you to put this whole situation behind you, and my counsel in that regard still stands. What’s done is done. And as you stated, you wouldn’t do anything differently. But . . . that said, though the war is over, tensions are still running high, and certain people’s loyalties continue to be held in question.”

“As in mine.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes, ma’am. As in yours.” Remembering what she’d said about how she appreciated his speaking the truth to her, he forged on, hoping she would still feel that way when he was done. “As you know . . . a court of law is only as fair and just as is the judge seated on the bench, or the people seated in the jury. People are responsible for interpreting the law, and yet we each come with our own individual backgrounds and experiences and, therefore, biases.”

He looked back at her but she still faced the window. “At the end of the war, ma’am . . . when most people were struggling to find food and shelter for their families—many of whom still are—you managed to outmaneuver two armies and transport twenty-eight hundred bales of cotton through enemy lines. And you sold it . . . for one million dollars, and then set out on a grand tour of Europe. While others, say a judge or a jury of your peers”—he watched her closely, trying to read

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher