![Always Watching]()

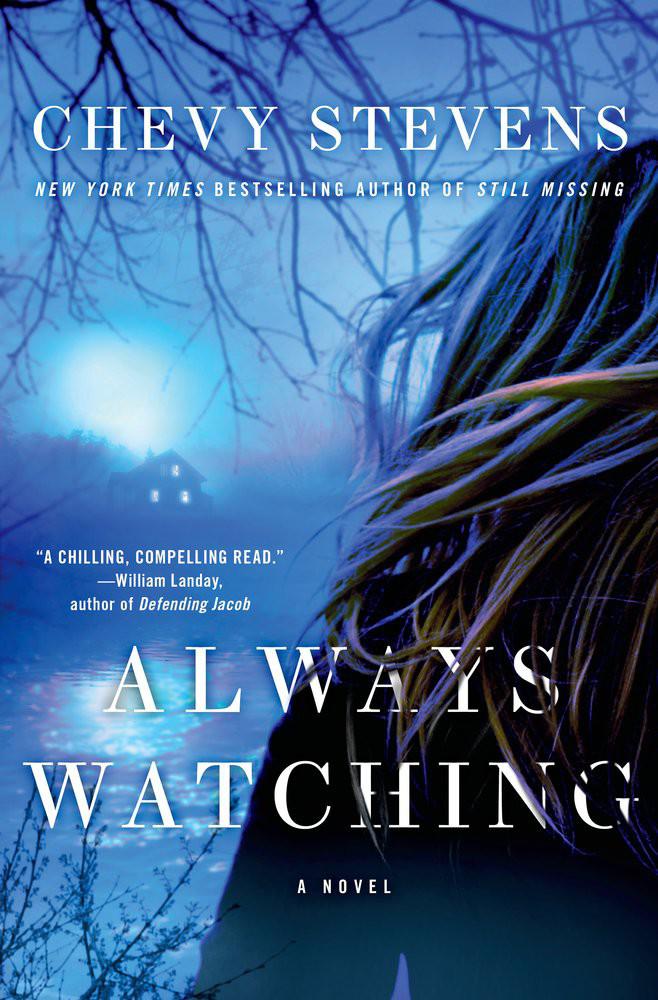

Always Watching

“They can live up to thirty-five years, you know.”

I did know, but I said, “Really? I wonder if she’s the same one we used to feed.”

She shrugged. “Not like she’d remember us.”

I waited for a beat, hoping she’d elaborate, but she was focused on the seal. I said, “I didn’t know you still come here.”

She looked at me, one brow raised. The message was clear: You don’t know anything about my life anymore.

“I’ll have to visit her more often. I live in Victoria now.…” Throwing out a hook.

She glanced at me again, pulling her coat tight around her body as the wind came off the ocean, her hair picking up at the ends, her cheeks pink. I ached at how beautiful she was, seeing Paul’s and my love in every cell of her body. Her long hands: his. Her coloring: mine. Her legs that went on for miles: his. Her love of the earth and animals: ours. Her pain: mine.

I said, “You look well.”

It was meant as a compliment, but she caught the tone of relief.

“You mean I don’t look like an addict.”

“That’s not what I meant.” But it was.

She snorted, turned back to the seal. “Why did you move down here?”

“I got a job at the hospital. And I wanted to be closer to you.” She didn’t say anything. But her cheeks flushed. Pleasure or anger? I added, “It’s your birthday coming up. Would you like to go for dinner? Anywhere you like. Or you can come see my new house.” I gestured toward Fairfield. “I have a potting shed in the back. I’ve been trying to grow bonsai trees, but I suck at it.” Did I really just say suck? What was I trying to prove? That I was cool? That she should love me? But I still couldn’t help adding, “There’s an extra room if you ever need a place to crash.” I was disgusted with my desperate attempts to relate.

“I’m doing okay. You don’t have to worry about me.”

I laughed, trying to ease the tension. “It’s hard for a mother not to worry about her child, even if the child is grown-up and making her own decisions.” She didn’t smile. I changed my tone. “But I’m happy to hear you’re doing well.”

She tilted her chin back, looking at me with those soulful blue eyes that had lied to me so many times, and said, “I’ve been clean for a couple of weeks.”

I was a psychiatrist, trained to say the right things at the right time, but now my mind spun with the worry of saying the worst thing: sound too encouraging and risk sounding patronizing; ask the wrong question and risk angering her; don’t say enough and risk sounding uncaring.

I settled on, “That’s great. Are you in a program?” The last part had slipped out before I remembered what a hot topic it was for her, how much she’d hated the rehab I sent her to as a teen. She’d called, crying, but I’d refused to pick her up, telling her she’d made a commitment. She broke out. Garret and I had found her hitching, just about to climb into a truck with three guys. I sat frozen in the car, terrified about what could’ve happened to her, wanting to lock her up for life, knowing that anything I said would just make it worse. Garret got out and talked to her until she finally got in the car. She hadn’t spoken to me for weeks, only telling me she’d stopped doing drugs, only to start again a month later.

“I don’t need a program. I’m doing it on my own.”

“I’m proud of you—that takes a lot of discipline.” And rarely works. “If you did ever want to get treatment—” Her jaw tightened, and I quickly added, “On an outpatient basis, of course, you could stay with me. I’d be happy to pay for it.”

She stood up. “You just can’t stop yourself, can you? You think you’re so helpful—you don’t help anything. ” And with that, she grabbed her packsack and stormed off. I stood there for a while afterward, my face hot with embarrassment, my eyes stinging with tears, and my heart full of regret.

I looked down at the seal. She turned and dove under the water, only the ripples on the water showing that she’d ever been there.

CHAPTER TWENTY

The rest of the afternoon I stayed close to home, puttering around in my garden, licking my wounds. My daughter’s words, and also my brother’s, had hit home. I knew there was some truth to what they were saying. I’d always had an urge to fix everything and everyone I came across—the same urge that had driven me into psychiatry. I’d turned that trait into a skill and learned that you could

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher