![Always Watching]()

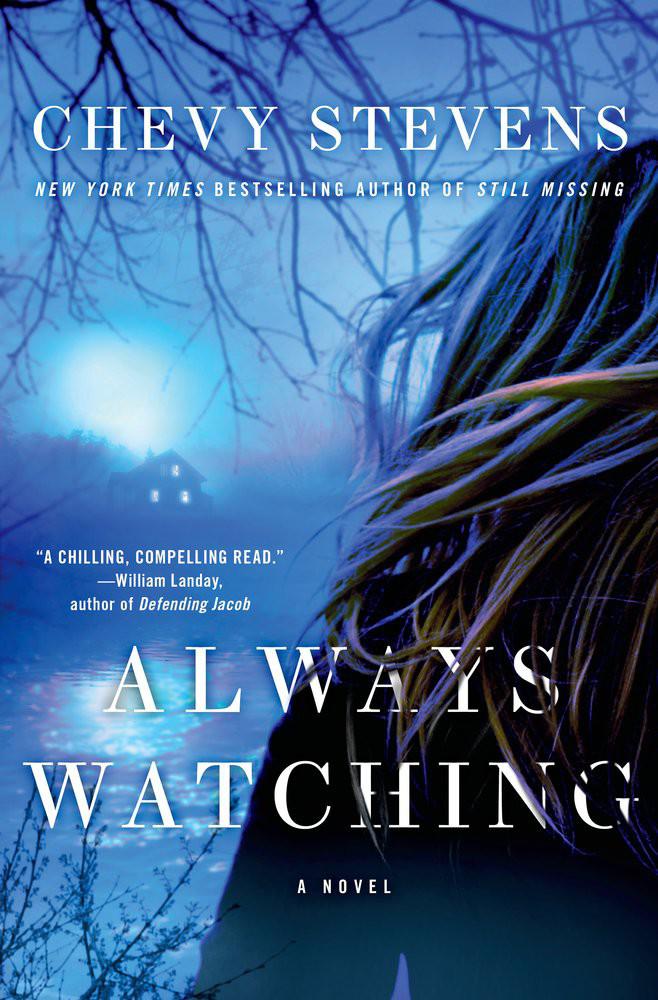

Always Watching

leaped over the fence—and was gone.

I spun around, wondering what had startled her. I didn’t see anything at the end of my driveway, or at the front of the house. I frowned, all my nerves standing at attention as an edgy feeling of being watched spread over me. Was someone there? Ever since I’d made my police report, I’d been jumping at every sound. Then a man called his dog from the end of the street. So that was what scared her—a dog running by. I let out my breath.

I grabbed my bike off the back deck, where I now stored it instead of the shed, tossed my purse in the front basket, and pedaled down to the waterfront walkway along Dallas Road. I paused to watch the winter waves against the breakwater. In the summer, enormous cruise ships docked at Ogden Point, and the Inner Harbor teemed with camera-happy tourists and the clip-clopping of horse-drawn carriage rides. Victoria came alive with music and arts festivals, concerts in the parks, fireworks celebrations, float planes zooming in and out of the harbor, boats from all over the world dotting the water. I was looking forward to the summer season, but I also enjoyed these last few days of winter, when Victoria still mostly belonged to the locals.

I took a moment to breathe in the fresh air, glad I’d decided to get out of the house. After a moment, I continued on to Fisherman’s Wharf. Paul and I had often taken the kids there to feed the harbor seals—you could buy a bucket of fish for a dollar. Lisa had been obsessed and talked about becoming a marine biologist for years. She’d loved animals ever since she was little, begging to come to the clinic with her father, sitting up with a sick animal. Many nights we had to drag her home. We’d been sure she’d become a vet of some kind, but that was another dream that had fallen by the wayside. I still liked to go down and see the seals myself, though it was lonelier now.

I grabbed a London Fog tea at the Moka House, then wheeled my bike down the ramp to the wharf. The fish-and-chip place was boarded up for the winter, but I was happy they were still in business—we used to take Garret and Lisa there, but Lisa would feed half her chips to the seagulls and the other half to the seals, so we had to keep an eye on her. Still lost in my thoughts, I noticed a young woman sitting on a picnic table, wearing a faded green cargo coat, a thick black knit scarf wrapped around her neck, tight jeans with ripped knees, old black Doc Martens with the top laces removed, and wool socks pulled up over the bottom of her jeans. Her face was turned, looking down at a seal bobbing in the water in front of her, so I couldn’t see her features. Then the woman glanced at me.

I was staring into my daughter’s face.

There was also instant recognition in hers. I fought the urge to rush forward and gather her in my arms, knowing she would just push me away. We were silent for a moment, assessing each other, collecting ourselves. I was happy to see that her skin was clear, with no sores—and no makeup, but she’d never needed it. I’d hated it when she circled her eyes and lips with black, never understood why she was hiding her beauty. Her eyes, the same blue as mine, were ringed in black eyelashes, but her facial structure was more angular, like her father’s. She’d grown her dark hair out and it was thick and wild around her face, ending far past her shoulders in light auburn tips; whether from sun or bottle, it suited her.

I smiled. “Lisa, I’m so glad to see you.” I felt a stab of grief that I should be talking to my daughter like a stranger, followed by bitter irony that I’d been searching the streets for her but never thought to look at one of her favorite places.

“Hey.” She turned back to the seal, reached into the bucket beside her, tossed a fish.

I stood awkward. She hadn’t told me to go away, but she hadn’t provided an invitation either. Now that I finally had her within my reach, contact I’d craved for months, I was unsure of myself. I inched forward, standing near her but still maintaining some distance, nervous about saying anything that would make her bolt. A pulse fluttered in her neck, and though her face was calm, I wondered if the pulse belied her own inner turmoil. My head was filled with anxious questions. Where are you living? Do you need food? Are you still doing drugs?

She twisted slightly, glanced at me.

I pretended to watch the seal, smiling at her antics.

She said,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher