![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

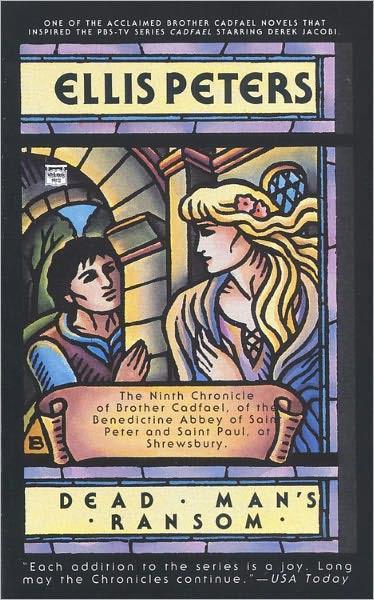

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

together a while longer, anything to prevent your being sent away, back to Wales. Anything! You said you would kill, and now you have killed, and God forgive me, I am guilty along with you.'

Elis stood facing her, the poor lucky lad suddenly most unlucky and defenceless as a babe. He stared with dropped jaw and startled, puzzled, terrified face, struck clean out of words and wits, open to any stab. He shook his head violently from side to side, as if he could shake away a nightmare, after the fashion of those clever dreamers who use their fingers to prise open eyelids beset by unbearable dreams. He could not get out a word or a sound.

'I take back every evidence of love,' raged Melicent, her voice like a cry of pain. 'I hate you, I loathe you... I hate myself for ever loving you. You have so mistaken me, you have killed my father.'

He wrenched himself out of his stupor then, and made a wild move towards her. 'Melicent! For God's sake, what are you saying?'

She drew back violently out of his reach. 'No, don't touch me, don't come near me. Murderer!'

'This shall end,' said Hugh, and took her by the shoulders and put her into Sybilla's arms. 'Madam, I had thought to spare you any further distress today, but you see this will not wait. Bring her! And sergeant, have these two into the gatehouse, where we may be private. Edmund and Cadfael, go with us, we may well need you.'

'Now,' said Hugh, when he had herded them all, accused, accuser and witnesses, into the anteroom of the gatehouse out of the cold and out of the public eye, 'now let us get to the heart of this. Brother Edmund, you say you found this man in the sheriff's chamber, standing beside his bed. How did you read it? Did you think, by appearances, he had been long in there? Or that he had but newly come?'

'I thought he had but just crept in,' said Edmund. 'He was close to the foot of the bed, a little stooped, looking down as though he wondered whether he dared wake the sleeper.'

'Yet he could have been there longer? He could have been standing over a man he had smothered, to assure himself it was thoroughly done?'

'It might be interpretable so,' agreed Edmund very dubiously, 'but the thought did not enter my mind. If there had been anything so sinister in him; would it not have shown? It's true he started when I touched him, and looked guilty, but I mean as a boy caught in mischief, nothing that caused me an ill thought. And he went, when I ordered him, as biddable as a child.'

'Did you look again at the bed, after he was gone? Can you say if the sheriff was still breathing then? And the coverings of the bed, were they disarranged?'

'All was smooth and quiet as when we left him sleeping. But I did not look more closely,' said Edmund sadly. 'I wish to God I had.'

'You knew of no cause, and his best cure was to be let alone to sleep. One more thing, had Elis anything in his hands?'

'No, nothing. Nor had he on the cloak he has on his arm now.' It was of a dark red cloth, smooth surfaced and close woven.

'Very well. And you have no knowledge of any other who may have made his way into the room?'

'No knowledge, no. But at any time entry was possible. There may well have been others.'

Melicent said with deadly bitterness: 'One was enough! And that one we do know.' She shook Sybilla's hand from her arm, refusing any restraint but her own. 'My lord Beringar, hear me speak. I say again, he has killed my father. I will not go back from that.'

'Have your say,' said Hugh shortly.

'My lord, you must know that this Elis and I learned to know each other in your castle where he was prisoner, but with the run of the wards on his parole, and I was with my mother and brother in my father's apartments waiting for news of him. We came to see and touch, my bitter regret that I am forced to say it, we loved. It was not our fault, it happened to us, we had no choice. We came to extreme dread that when my father came home we must be parted, for then Elis must leave in his place. And you, my lord, who best knew my father, know that he would never countenance a match with a Welshman. Many a time we talked of it, many a time we despaired. And he said, I swear he said so, he dare not deny it, he said he would kill for me if need be, kill any man who stood between us. Anything, he said, to hold us together, even murder. In love men say wild things. I never thought of harm, and yet I am to blame, for I was as desperate for love as he. And now he has done what he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher