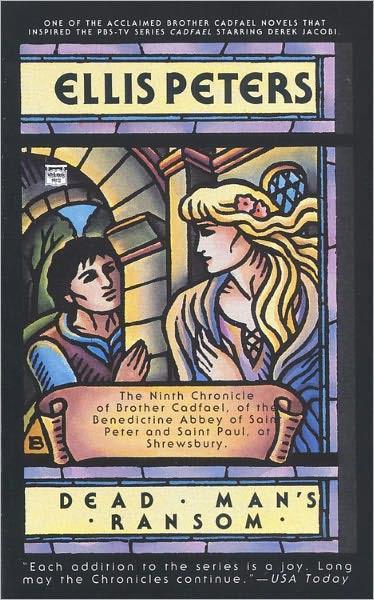

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

knee, which would not go fairly under him as yet, but threatened to double all ways to let him fall. When he was ready he looked very young, neat and solemn, and understandably afraid. He stood twisted a little sideways, favouring the knitting rib that shortened his breath. Melicent kept a hand ready, close to his arm, but held off from touching.

'I have sent Eliud back to Wales in my place,' said Elis, stiff as much with apprehension as with resolve, 'since I owe him a life. But here am I, at your will and disposal, to do with as you see fit. Whatever you hold due to him, visit upon me.'

'For God's sake sit down,' said Hugh shortly and disconcertingly. 'I object to being made the target of your self-inflicted suffering. If you're offering me your neck, that's enough, I have no need of your present pains. Sit and take ease. I am not interested in heroes.' Elis flushed, winced and sat obediently, but he did not take his eyes from Hugh's grim countenance.

'Who helped you?' demanded Hugh with chilling quietness.

'No one. I alone made this plan. Owain's men did as they were ordered by me.' That could be said boldly, they were well away in their own country.

'We made the plan,' said Melicent firmly.

Hugh ignored her, or seemed to. 'Who helped you?' he repeated forcibly.

'No one. Melicent knew, but she took no part. The sole blame is mine. Deal with me!'

'So alone you moved your cousin into the other bed. That was marvel enough, for a man crippled himself and unable to walk, let alone lift another man's weight. And as I hear, a certain miller of these parts carried Eliud ap Griffith to the litter.'

'It was dark within, and barely light without,' said Elis steadily, 'and I...'

'We,' said Melicent.

'... I had already wrapped Eliud well, there was little of him to see. John did nothing but lend his strong arms in kindness to me.'

'Was Eliud party to this exchange?'

'No!' they said together, loudly and fiercely.

'No!' repeated Elis, his voice shaking with the fervour of his denial. 'He knew nothing. I gave him in his last drink a great draught of the poppy syrup that Brother Cadfael used on us to dull the pain, that first day. It brings on deep sleep. Eliud slept through all. He never knew! He never would have consented.'

'And how did you, bed held as you were, come by that syrup?'

'I stole the flask from Sister Magdalen,' said Melicent. 'Ask her! She will tell you what a great dose has been taken from it.' So she would, with all gravity and concern. Hugh never doubted it, nor did he mean to put her to the necessity of answering. Nor Cadfael either. Both had considerately absented themselves from this trial, judge and culprits held the whole matter in their hands.

There was a brief, heavy silence that weighed distressfully on Elis, while Hugh eyed the pair of them from under knitted brows, and fastened at last with frowning attention upon Melicent.

'You of all people,' he said, 'had the greatest right to require payment from Eliud. Have you so soon forgiven him? Then who else dare gainsay?'

'I am not even sure,' said Melicent slowly, 'that I know what forgiveness is. Only it seems a sad waste that all a man's good should not be able to outweigh one evil, however great. That is the world's loss. And I wanted no more deaths. One was grief enough, the second would not heal it.' Another silence, longer than the first. Elis burned and shivered, wanting to hear his penalty, whatever it might be, and know the best and the worst. He quaked when Hugh rose abruptly from his seat.

'Elis ap Cynan, I have no charge to make in law against you. I want no exaction from you. You had best rest here a while yet. Your horse is still in the abbey stables. When you are fit to ride, you may follow your foster brother home.' And before they had breath to speak, he was out of the room, and the door closing after him.

Brother Cadfael walked a short way beside his friend when Hugh rode back to Shrewsbury in the early evening. The last days had been mild, and in the long green ride the branches of the trees wore the first green veil of the spring budding. The singing of the birds, likewise, had begun to throb with the yearly excitement and unrest before mating and nesting and rearing the young. A time for all manner of births and beginnings, and for putting death out of mind.

'What else could I have done?' said Hugh. 'This one has done no murder, never owed me that very comely neck he insists on offering me. And if I had hanged him

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher