![Buried Prey]()

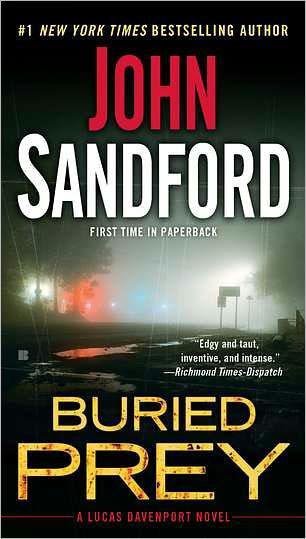

Buried Prey

endomorph, rather than simply fat, came and leaned in her doorway and asked, “We gonna talk to her?”

“Got to,” Marcy said. “She’s been all over the TV, she’s got that BCA face . . . we gotta talk to her.”

“For real, or for PR?”

Marcy yawned. Her boyfriend was in Dallas, and she was restless and a little lonely: “PR, mostly . . . she’s told that story so often I got it memorized.”

“You want me to do it?”

“I want you to come along when I do it—follow me over there. I can go home from there. You can take notes. Somebody’s got to take notes.”

Buster got the address from the DMV, and a cell phone number from someplace else. Kelly Barker would be pleased to talk to Sherrill; she’d be at home all evening.

So Marcy and Buster headed out in two cars, down I-35W through south Minneapolis, past the airport and then west on I-494 and south again, a half-hour of easy driving, the sun slanting down toward the northwestern horizon.

Marcy thought about Davenport—he really was an arrogant bastard in a lot of ways, good-looking, rich, flaunting it with the car and the outrageously gorgeous Italian suits. But they’d once been involved in a case that led more or less directly to bed . . . forty days and forty nights, as Davenport referred to their affair. It had been short but sweet, and she still had a soft spot for him.

If he ever left Weather, would Marcy go back? Well, he was never going to leave Weather, for one thing. He was so loyal that once you were his friend, you stayed his friend, even if you didn’t want to . . . and he was married to Weather and that would last right up to the grave, no doubt about it. But, speaking of the grave, if Weather got hit by a train, and Davenport, after a suitable interval, expressed a need for some female companionship . . .

Maybe. But what about Rick? Well, Rick was interesting, but he made his money by calling people up on the telephone, and talking to them about investments. He liked having a cop on his arm, and insisted that she carry a gun when they went out at night. She would have anyway; she’d always liked guns.

Still, she wasn’t much interested in being somebody’s trophy. She’d gone out with an artist for a while, a guy who reminded her of a crazier version of Davenport—in fact, he’d been a wrestler at the U at the same time Davenport had been playing hockey, and they knew each other, part of the band of jock-o brothers.

Huh. The artist had been . . . hot. Crazy, maybe, but hot. After they’d split up, he’d gone and married some chick he’d known forever, and Davenport had told her that he and the chick even went and had a kid.

Had a kid.

She’d like a kid . . . but, it’d have to be soon. Rick wasn’t the best daddy material in the world. He had the attention span of a banana slug, and didn’t seem like the kind who’d be interested in the poop-and-midnight-bottle routine.

There was another guy, too, an orthopedic surgeon who wore cowboy boots and rode cutting horses on the weekends, out of a ranch north of the Cities. He was divorced but getting ripe, looking at her, from time to time, and she felt a little buzz in his presence. And she liked horses.

Possibilities.

She smiled to herself and turned on the satellite radio. Lucinda Williams came up with “Joy,” quite the apposite little tune, given her contemplation of the boys in her life. . . .

WHILE SHE WAS HEADING SOUTH, the killer was roaming around Bloomington, going back again and again to Kelly Barker’s house, not knowing exactly what he planned to do; whatever it was, he had to wait until she got home, and she’d already kept him waiting so long that he felt the rage starting to burn under his belt buckle.

He was one morose and angry motherfucker, he admitted to himself, and things weren’t getting any better. He had no life, had never had one. He had a crappy house, a crappy van, a crappy income, and no prospects. He collected and resold junk. He was a junk dealer. He had a bald spot at the top of his head, growing like a forest fire at Yellowstone. He was so overweight he could barely see his own dick. He had recurrent outbreaks of acne, despite his age, and the cardiologist said that if he didn’t lose seventyfive pounds, he was going to die. And he had dandruff. Bad.

Dumb and doomed: even in Thailand, he could see the disregard, the contempt, in the eyes of the little girls he used. They weren’t even frightened of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher