![Darkfall]()

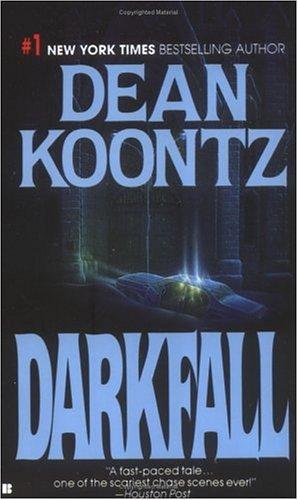

Darkfall

control for even a moment

Then God help us, Carver thought.

If He will help us.

If He can help us.

A hurricane-force gust of wind slammed into the building and whined through the eaves.

The window rattled in front of Carver, as if something more than the wind was out there and wanted to get in at him.

A whirling mass of snow pressed to the glass. Incredibly, those hundreds upon hundreds of quivering, suspended flakes seemed to form a leering face that glared at Hampton. Although the wind huffed and hammered and whirled and shifted directions and then shifted back again, that impossible face did not dissolve and drift away on the changing air currents; it hung there, just beyond the pane, unmoving, as if it were painted on canvas.

Carver lowered his eyes.

In time the wind subsided a bit.

When the howling of it had quieted to a moan, he looked up once more. The snow-formed face was gone.

He sipped his Scotch. The whiskey didn’t warm him. Nothing could warm him this night.

Guilt was one reason he wished he could get drunk. He was eaten by guilt because he had refused to give Lieutenant Dawson any more help. That had been wrong. The situation was too dire for him to think only about himself. The Gates were open, after all. The world stood at the brink of Armageddon-all because one Bocor , driven by ego and pride and an unslakeable thirst for blood, was willing to take any risk, no matter how foolish, to settle a personal grudge. At a time like this, a Houngon had certain responsibilities. Now was an hour for courage. Guilt gnawed at him because he kept remembering the midnight-black serpent that Lavelle had sent, and with that memory tormenting him, he couldn’t find the courage he required for the task that called.

Even if he dared get drunk, he would still have to carry that burden of guilt. It was far too heavy-immense-to be lifted by booze alone.

Therefore, he was now drinking in hope of finding courage. It was a peculiarity of whiskey that, in moderation, it could sometimes make heroes of the very same men of whom it had made buffoons on other occasions.

He must find the courage to call Detective Dawson and say, I want to help .

More likely than not, Lavelle would destroy him for becoming involved. And whatever death Lavelle chose to administer, it would not be an easy one.

He sipped his Scotch.

He looked across the room at the wall phone.

Call Dawson, he told himself.

He didn’t move.

He looked at the blizzard-swept night outside.

He shuddered.

IV

Breathless, Jack and Rebecca and the kids reached the fourth-floor landing in the brownstone apartment house.

Jack looked down the stairs they’d just climbed. So far, nothing was after them.

Of course, something could pop out of one of the walls at any moment. The whole damned world had become a carnival funhouse.

Four apartments opened off the hall. Jack led the others past all four of them without knocking, without ringing any doorbells.

There was no help to be found here. These people could do nothing for them. They were on their own.

At the end of the hall was an unmarked door. Jack hoped to God it was what he thought it was. He tried the knob. From this side, the door was unlocked. He opened it hesitantly, afraid that the goblins might be waiting on the other side. Darkness. Nothing rushed at him. He felt for a light switch, half expecting to put his hand on something hideous. But he didn’t. No goblins. Just the switch. Click . And, yes, it was what he hoped: a final flight of steps, considerably steeper and narrower than the eight flights they had already conquered, leading up to a barred door.

“Come on,” he said.

Following him without question, Davey and Penny and Rebecca clumped noisily up the stairs, weary but still too driven by fear to slacken their pace.

At the top of the steps, the door was equipped with two deadbolt locks, and it was braced by an iron bar. No burglar was going to get into this place by way of the roof. Jack snapped open both deadbolts and lifted the bar out of its braces, stood it to one side.

The wind tried to hold the door shut. Jack shouldered it open, and then the wind caught it and pulled on it instead of pushing, tore it away from him, flung it outward with such tremendous force that it banged against the outside wall. He stepped across the threshold, onto the flat roof.

Up here, the storm was a living thing. With a lion’s ferocity, it leapt out of the night, across the parapet, roaring

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher