![Empty Mansions]()

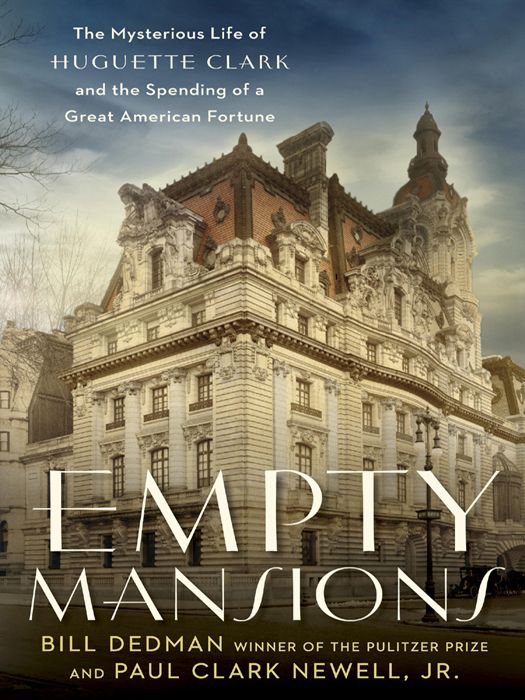

Empty Mansions

$5,899,133, earning nothing. The bankers, fearing they’d be sued for acting irresponsibly, wrote to her repeatedly, pleading with her to put the money in an interest-bearing account. Her attorneys and accountant urged the same, time after time. She told them she’d think about it, but she did nothing. Perhaps she preferred to keep the money where she could get at it quickly.

If she had put that $5,899,133 balance into a one-year certificate of deposit, then earning 5 percent, she would have earned $294,957 in interest, nearly enough to pay for a Louis XV rolltop desk.

BLOND HAIR AND A DIMPLE

H UGUETTE RECEIVED a plea for help in 1988 with a familiar postmark—Butte, Montana—and bearing the name Clark. Though the letter was too polite to say so, it was raising a philosophical question: Do children owe an obligation to the place where their parents got their start?

W.A.’s youngest son, Francis Paul Clark, known as Paul, was just sixteen when he died in March 1896. He was a student at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, preparing to attend Yale University. Paul was a shy boy, whose hobby was writing to famous artists to ask for their autographs. He died from a bacterial infection, erysipelas, which causes a painful rash known as Saint Anthony’s fire. W.A. was in Paris and came back to New York for the funeral. Paul was entombed at Woodlawn Cemetery alongside his mother.

As a memorial, W.A. donated $50,000 for the Paul Clark Home, which opened in Butte in 1900. The Associated Charities of Butte took care of children in the handsome three-story brick home on Excelsior Street, less than a mile from the Clark mansion where Paul had grown up. W.A. also left the home an endowment of $350,000 in his will.

Anna visited the home with young Andrée and Huguette and gave money for a grand piano for the children to play. She left the home $5,000 in her will, one of her smallest bequests.

The Paul Clark Home wasn’t strictly an orphanage; it also took in children whose parents were still living but couldn’t care for them anymore. In addition, the home provided free medical care for any child from Butte and day care for children of working mothers. It was not in a bad part of town; directly across the street were three identical homes for managers of Clark’s mines.

In 1988, the Paul Clark Home reached a crossroads, and the board of directors reached out to W.A.’s surviving daughter, Huguette, who was born ten years after Paul died. During the 1960s, it had been convertedinto a home for developmentally disabled young adults, whom the state was moving out of institutions. Now this Clark legacy needed a new mission, and it had bills to pay. The trust set up by W.A. in his will was providing only $29,000 of the $60,000 budget each year, and the home’s board hoped to raise $200,000 for a renovation. W.A.’s will had set up the home to exist for as long as his children and grandchildren should live. Well, his grandchildren were nearly all dead, but his daughter lived on. Was it Huguette’s wish, the home’s attorney asked, that it continue?

Huguette sent back, through her attorney, questions about the home’s finances, but she didn’t send any money.

In December 1988, the Paul Clark Home was converted into a Ronald McDonald House, providing a temporary home for families who have a child or family member in the hospital. So it continues today.

The home is still a comfortable spot, with a reading room and a sun parlor. And one can still see, in the upstairs dormitory, the charming bathrooms with little sinks all in a row at a child’s height, twenty for boys and twenty for girls, with numbered cubbies for their toiletries and beautiful rows of lockers made of oak.

Huguette received similar letters over the next few years from the YWCA of Los Angeles, where the $25,000 left by W.A. for a women’s home was not enough for its upkeep. This home was a memorial to her grandmother, Mary Andrews Clark. Huguette again asked questions but sent nothing.

• • •

On May 18, 1993,Huguette was a bidder at a Sotheby’s auction fortwo antique French dolls. The first, in Lot 219, was a Jumeau triste pressed bisque doll, circa 1875, with a dimple in the chin, fixed brown glass paperweight eyes, pierced ears, blond mohair wig, in cream lacy overdress with Eau-de-Nil silk below and cream lacy and silk bonnet. The estimate was $12,000 to $15,000. She authorized her attorney to bid up to $45,000, but got it

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher