![Here She Lies]()

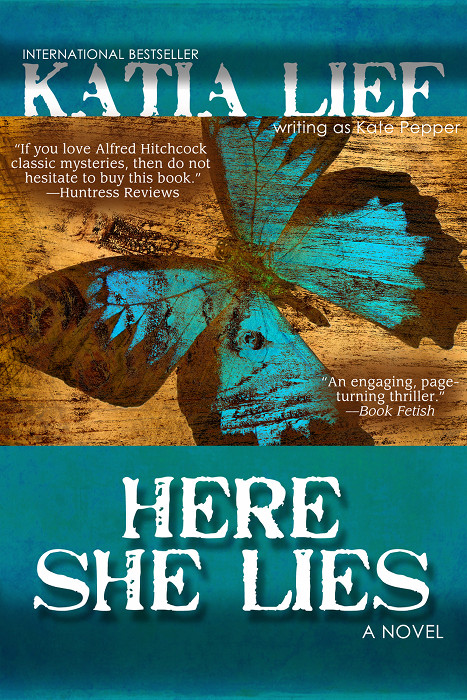

Here She Lies

holding Lexy, both of ustwisting to make eye contact with each other, and printed it. Half an hour later I was sitting in Julie’s car, alone, equipped with her ID and a suitcase of clothing to last two days and nights in the city.

I sat quietly in the car, in the dark, in the cold. Inside the big red house with its warmly lit windows were my sister and baby. Lexy didn’t understand yet that I was leaving for longer than usual. I could go back inside, scrap the whole thing. I didn’t want to go, but the plan was in motion. I felt certain I was doing the right thing. Yet I didn’t. Was I making a stupid mistake? After all, Bobby continued to assert his innocence. And I kept hearing Detective Lazare’s voice warning me that “someday you may need to fall back on that to comfort yourself.” Fall back on what? What was I so sure of, exactly? Had I left Bobby because I wanted to quit my job and leave Kentucky? Because my hormones were raging so loudly I couldn’t hear basic common sense? But the credit card bills. And the love letters. And the details.

I put Julie’s car into Drive and pulled away from the house.

Chapter 5

I arrived late at my father’s East Fifty-sixth Street pied-à-terre; well, that’s what he called it when we were girls and he was alive and we would come into the city occasionally from our Connecticut home. It was a crumbling studio apartment whose rent-controlled lease he’d taken over as an aspiring young writer, one of those gifts you just fall into. In the early eighties, when the building went co-op, he bought in at an amazing price. It was the best, and possibly only, investment he ever made. At his death, Julie and I inherited the place, and when we came of age, we kept it. Why not? It was a paid-off crash pad in the city of cities. Not suitable for my family or Julie’s extravagant taste, but it was ours.

I lugged my suitcase and garment bag up the five flights. The studio was predictably musty, so I immediately opened both windows. Night air trickled in with its pleasant springtime bite and I felt a little bit at home. This tiny space was so familiar: four cream-colored paint-crusted walls defining a twelve-by-twelvecube of a room with an incongruously high fifteen-foot ceiling. The small, dusty chandelier no one could reach, an old Murphy bed that had been here when Dad originally got the place, a small table and two ornately carved wooden chairs. The kitchen consisted of a couple of time-worn appliances jammed in one corner; there were no counters or drawers and in lieu of a cupboard there were three dusty shelves. The place was a hovel — presumably the only apartment in this co-op building that had never been renovated — but I was glad to be here. I opened my suitcase on the table, brushed my teeth, lowered the Murphy bed, made it up with clean sheets, stripped naked, pumped some breast milk, which I stowed in the tiny freezer, and went to sleep.

I was up by six. The orientation wasn’t until ten, so I pumped milk and then went out for breakfast at the same diner where Mom and Dad used to take us for lunch when we visited the studio as children. I bought a New York Times and sat on a ripped vinyl stool dipping toast into runny eggs and drinking decaf coffee that was remarkably delicious. It was very strange being alone here, family-less, without Lexy. I ached with missing her and tried to keep my mind off all my doubts and to force myself to go along with the program I had set for myself.

I expected the job orientation to be a breeze. It was a big corporate hospital chain that held new-employee orientations once a month. You would learn their rules and they would further process your paperwork and get a chance to eyeball you in advance in case the off-site interviewer had made some awful mistake. I hadplanned, after the orientation, to go apartment hunting, giving myself this afternoon and tomorrow to look, but decided on impulse that that could wait. I missed Lexy way too much to stay. As soon as I was done at the hospital, I decided, I would return to Great Barrington.

I finished my coffee and went back to Dad’s to shower and change. I felt uncomfortably raw, hyper-aware that one way or another this was going to be a pivotal day — depending a lot on what Bobby would tell me after his session with his computer sleuth — that I was either beginning a new life or spinning my wheels. I dressed in the same interview suit I’d worn two years ago for the prison

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher