![Here She Lies]()

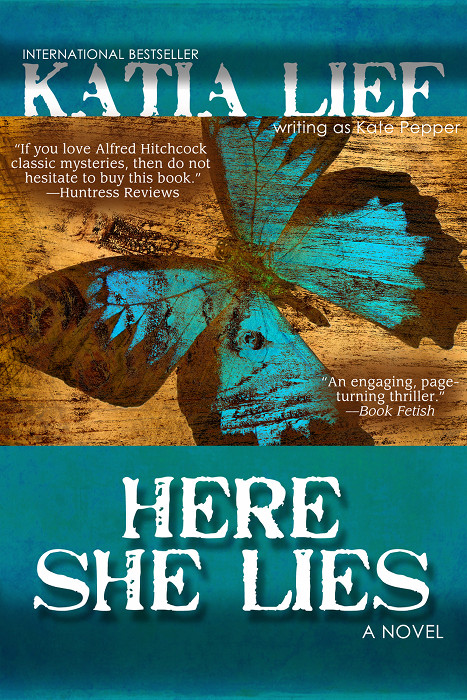

Here She Lies

us by seven. And Julie, don’t hold dinner.”

“I never eat before seven, anyway.”

Having grown accustomed to late-afternoon dinners (Bobby and I were in bed by eight thirty to be up at five, day care at six thirty, work by seven), I had forgotten how skewed my hours had become. Before Kentucky and Bobby and Lexy and the good ol’ Public Health Service, I too used to eat dinner at seven, eight, even nine o’clock.

“I’ll have to nurse Lexy as soon as I get there and throw her into bed, so just eat when you’re hungry. Did you get the—”

“Crib’s all set up. I got the cutest sheets. You’ll see.”

I had asked her to rent a crib for the summer, but Julie being Julie (she was a successful independent marketing consultant, apparently some kind of sought-after guru), she had gone out and bought one.

“Did you—”

“Yes, Annie, I washed the sheets first. Just get in the car and be here, okay?”

By the time we picked up the rental car, Lexy had had enough of traveling and she didn’t want to get into the car seat. She wanted to roll around the floor and practice grabbing for toys.

“Just a little longer, sweet baby. Promise.”

I ran my hand over her peachy wisps of hair and kissed her forehead, both cheeks, her dimpled chin, her button nose. She laughed, then immediately cried. Her little face screwing up so suddenly brought me to tears. I had felt like crying for hours but hadn’t wanted to attract attention to myself on the plane. All day I had felt that everyone could see me for what I really was: awife who had left her husband, a mother who had taken a child from a father, a woman who had lost hope in a man. Did it show? I knew that from now on, when people mentioned the Goodmans, it would be with the tagline “that broken family.” I was Anais (Annie) Milliken-Goodman. (Anna-ees, the French pronunciation. Naming us Anais and Juliet had been a flight of fancy in the romantic early years of our parents’ marriage.) Would I drop Goodman from my name? Slice off the dangling hyphen? Go back to square one? If I did, then Lexy and I would officially be Alexis Goodman and Anais Milliken. But I had always wanted to share a last name with my child. Maybe we could drop our last names all together; she could be just Lexy and I could be just Annie. We could start a band. A sob ratcheted up my throat and escaped as a shout. I felt like such a fool. What had I done?

A headache blossomed as the little blue car’s engine leapt into gear. The jolt quieted Lexy and I felt guiltily indebted to the sudden, unnerving grind of noise. Poor baby. What did she make of all this? Did she know something momentous was happening today? That the day was a knife carving a groove in our lives between before and after? Maybe I was wrong, but I sensed she felt the cut, the separation, as deeply as I did.

Why had Bobby done it? Why hadn’t I been enough for him? There was a time I would have bet my soul that he and I were made for each other. With him, I had felt almost as right as I did with my identical twin: one person, joined in separate bodies.

I switched on the radio and we listened to classical music as we drove out of Albany toward the New York — Massachusettsborder. When Lexy sighed, deep and long, I felt myself relax a notch. In the rearview mirror I saw she had fallen asleep and I whispered “thank you” to the windshield. Humming along the highway, we consumed the miles to Great Barrington. To Julie’s. I had never been to her new house, but I felt I was going home. I was as eager to arrive as I had ever been to get anywhere. Home after work. Bed after a tiring day. Birth after labor. Love after loneliness. Resolution after doubt.

After weeks of agony, I had a made a decision. I couldn’t just stay there, living with Bobby, sleeping with him, working side by side, wondering who she was. I couldn’t agree that black was white or white was black when all I saw was shades of gray. I would not repeat my mother’s mistake, accepting my father’s lies for years until finally it turned out her suspicions had been correct: he was cheating. It was terrible watching her struggle to recover from her own self-deceptions, her willingness to believe his lies. In the end, she never did recover — cancer got her first. We were only ten when our mother died, leaving me with the conviction that a woman should never compromise on the truth. At twelve, when our father died suddenly in a car accident, I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher