![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

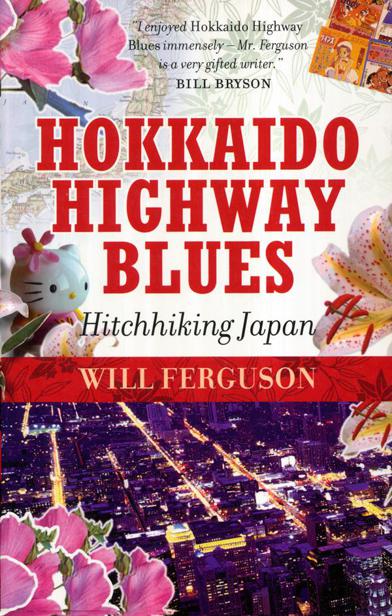

Hokkaido Highway Blues

but now I realized what I had done and the crumpled carbon copy in my pocket seemed like a personal citation. I might even get it framed. I really must send them a thank-you note, I said to myself. That and some pimple cream for Junior, ha ha! I did a little victory dance and whooped it up some more, and then I realized that I did not have a clue in hell where I was.

12

GRASSY FIELDS AND cracked, overgrown pavement. A few farmhouses and a rim of mountains on the horizon. That was about it. I didn’t know where I was or even what city I was pointed toward. I was shuffling through my maps, when a single white car appeared in the distance like a lone horseman in a Macaroni Western, shimmering in the heat, growing larger. “Please oh please oh please don’t go by,” I whispered, and at the last minute I lost my nerve and instead of thumbing I leapt out and flagged him down. All I can say is, thank God it wasn’t another patrolman. Blocking traffic is probably a violation of some bylaw.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m lost. Can you tell me where the road to Joetsu is?” Inside was a bewildered-looking man in a denim shirt. “I will take you to Joetsu,” he said, but I had learned my lesson.

“Where are you going?” I asked.

“I’ll take you to Joetsu, don’t worry. Please get in.”

“Don’t say you’re going to Joetsu unless you really are going to Joetsu.”

“I don’t mind. Please get in.”

“Not until you tell me how far you’re going.”

“Toyama.”

“Ha! That’s nowhere near Joetsu. I will get in, but only if you promise that you won’t go any farther out of your way than Toyama. Agreed?” Hitchhiking in Japan can be so surreal.

Hitoshi Kusunoki was an art teacher at a small-town junior-high school. He spoke English about as well as I spoke Japanese, so we communicated in a mix of the two; he addressed me in English, I answered in Japanese. It worked out quite well.

The landscape expanded. The plains were wider, the fields emptier, the mountains more distant, the ocean out of view. It was, in a way, monotonous, a strictly functional landscape, pared down to the minimal requirements: mountains, field, road, sky.

Incredibly, Hitoshi had come to this very scenery for artistic inspiration. He had a carton of colored pencils and paints and was hoping to stop along the way. He was going to Toyama City for a teachers’ conference—“We must strive to be ambitious and, international”—but was taking it slowly along side roads, enjoying the view.

“The view?”

“It’s so open,” he said. “Spacious.”

“I don’t know, I kind of miss the usual Japanese clutter, the small villages, the little valleys.”

“Hokkaido is even more spacious,” he said. “You will see.“ He then asked me how many cars it had taken so far.

“I think you’re number twenty-seven.”

“Twenty-seven cars. Twenty-seven ‘Hellos.’ Twenty-seven ‘What is your names?’ It must be, every time, the same questions, right? Can you eat Japanese food? Do you like Japan? What do you think of Japan? You must be tired, to always talk about Japan.”

“Sometimes.”

“Don’t worry,” he said. “I know about Japan. Tell me something else.”

“Like what?”

“Other places.”

I tried to trace back the routes and tangents that had brought me here, to this particular place at this particular time. It seemed as random as the path rain takes across a car window. How to pick the one definitive place, the one image that shaped you above all others?

The aurora borealis of my childhood? Being robbed at knifepoint in Amsterdam? (A terrific anecdote, that, but in truth a horribly emasculating experience.) A certain pub in London’s Soho. An apartment in Québec City. The week I spent camped in that large bog sometimes referred to as Scotland. And what else? Korea. Indonesia. The Great Wall. Just postcards, really, when all is said and done. And the thought gnawed at my heart: everything I had done, a collection of postcards, like a zoetrope made to resemble motion while turning in circles.

“I once worked for a short time in South America,” I said, “and I lived with a family in a village at the top of the world. I was nineteen years old and I was going to live forever.”

Hitoshi said: “When you remember that village, what do you remember best?”

I thought a moment. “The sound of roosters in the morning. The smell of sugarcane, like wet grass.” And it all came back

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher