![Kushiel's Dart]()

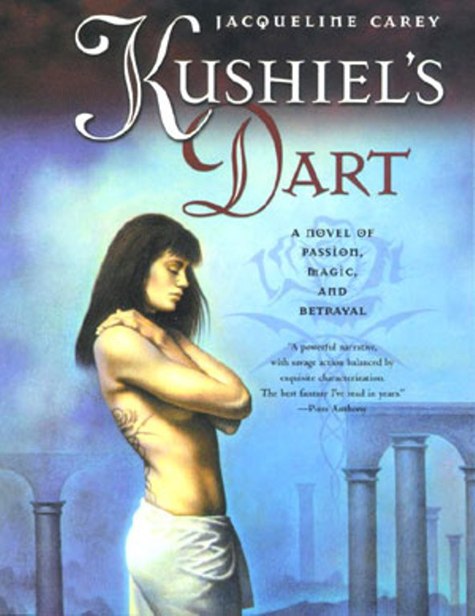

Kushiel's Dart

see our road."

I went to him, then; they left us alone, muttering. Joscelin watched silently, offering no comment.

"You can, Hyacinthe. I know you can," I said, taking his arm. "It's only mist! What's that to the veils of what-might-be?"

"It is vrajna ." He shivered, cold beneath my grasp. "They were right, Manoj was right, this is no business for men."

Waves lapped at the sides of our ship, little waves, moving us nowhere. We were becalmed. The rowers had paused.

"Prince of Travellers," I said. "The Long Road will lead us home. Let it show the way."

Hyacinthe shivered again, his black gaze blurred and fearful. "No. You don't understand. The Long Road goes on and on. There is no home for us, only the journey."

"You are half D'Angeline!" I raised my voice unintending, shaking him. "Hyacinthe! Elua's blood in your veins, to ground you home, and Tsingani, to show the way. You can see it, you have to! Where is the Cullach Gorrym?"

His head turned, this way and that, dampness beading on his black ringlets. "I cannot see it," he repeated, shuddering. "It is vrajnal They were right. I should never have looked, never. Men were not meant to part the veils. Now this mist is sent to veil us all, for my sin."

I stood there, my fingers digging into his arm, and cast my gaze about. Up, upward, where the sun rode faint above the mists, a white disk. The ship's three masts rose, bobbing, to disappear in greyness. "If you cannot see through it," I said fiercely, "then see over it!"

Hyacinthe looked at me slowly, then up at the tallest mast, the crow's nest lost in the mists. "Up there?" he asked, his voice full of fear. "You want me to look from up there?"

"Your great-grandmother," I said deliberately, "gave me a riddle. What did Anasztaizia see, through the veils of time, to teach her son the dromonde ? A horse-drawn wagon and a seat by the kumpania's fire, or a mist-locked ship carrying a ring for a Queen's betrothed? It is yours to answer."

He looked for a long time without speaking.

And then he began to climb.

For uncountable minutes we were all bound in mist-wreathed silence, staring into the greyness where Hyacinthe had disappeared, far overhead. The ship rocked gently, muffled waves lapping. Then his voice came, faint and disembodied, a single lonely cry. "There!"

It might have been the depths of the ocean he pointed to for all any of us could see. Quintilius Rousse cursed, fumbling his way back toward the helm. "Get a relay!" he roared, setting his sailors to jumping. "You! And you!" He pointed. "Move! Get up that rigging! Marchand, call the beat, get the oarsmen to put their backs to it! We follow the Tsingano's heading!"

All at once, the ship was scrambling into motion, men hurrying hither and thither, carrying out Rousse's orders. "Two points to port!" the call came, shouted down the rigging. "And a light in the prow, Admiral!"

The mighty ship turned slowly, nosing through the mist. Far forward, a lantern kindled, a single sailor holding it aloft at the very prow. Down came the shouted orders, and Rousse at the helm jostled the ship into position, until the lantern was aligned with Hyacinthe's pointing finger high in the crow's-nest, unseen by those of us below.

"That's it, lads!" he cried. "Now row! Out oars!"

Belowdecks, the steady beat of a drum sounded, Jean Marchand's voice rising in counterpoint. Two rows of oars pulled in unison, digging into the sea. The ship began to move forward, gaining speed, travelling blind through the mists.

I did not need to be a sailor to guess how dangerous it was, so close to a strange, unseen coast. I joined Joscelin, and we stood together watching Quintilius Rousse man the helm, his scarred face alight with reckless desperation, having cast his lot. How long we sailed thusly, I cannot say; it seemed the better part of a day, though I think it no more than an hour.

Then came another cry, and a change of direction. On Hyacinthe's lead, we turned our prow toward land, invisible before us ... but, the last time glimpsed, close by. The Admiral's face grew grim as he held the course, white-knuckled. For the first time all day, a wind arose, sudden and unexpected, filling our sails. The rowers put up their oars, resting, as we raced before the wind like a bird on the wing.

Out of the mists, and into sunlight, gleaming on the waters, heading straight into a narrow, rocky bay that cut deep into the shoreline.

A great cheer arose, dwarfing in sound the one that they'd

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher