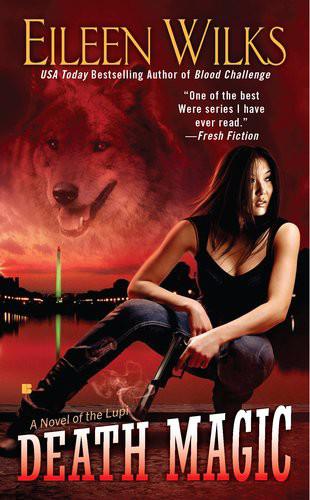

![Lupi 08 - Death Magic]()

Lupi 08 - Death Magic

He’d swum in that pool faithfully for years, until he grew too weak.

A fat moon peeked out from the branches of the enormous oak that anchored the east side of the yard. Nearly full, he noted. So near he couldn’t pick out the difference by eye, but he knew when the full moon would arrive this month. That particular datum mattered these days.

Deb had poured so much of herself into their land. It was a mistake to see anyone wholly through the prism of their Gift, but there was no denying that Earth-Gifted tended to put down roots. He was not surprised she’d refused to leave her home, to go into hiding as he’d so urgently asked her to do.

And, he admitted in this four-in-the-morning privacy, he’d wanted her to refuse. However sternly he hid that from her, that’s what he’d wanted. More time with Deb. Every moment he could steal.

This wasn’t the first time he’d had that dream.

That trace of sidhe blood was responsible for more than his allergy to some metals. Though he had no proof, Ruben felt confident it was also responsible for his Gift. Not the existence of it, perhaps, but the strength. Precognition was actually very common. Accurate precognition was not. Accuracy such as he possessed was unheard of.

He was very, very good. Better than he’d allowed any tests to show. People were uncomfortable enough around someone who’d shown he could, at times, sense the future with seventy percent accuracy. They simply would not believe he was right ninety-eight percent of the time.

Deb knew, however. Deb knew almost everything there was to know about him.

Almost.

Precognition took many forms. Visual precogs—those who literally saw the future—were the rarest and statistically the most accurate, but they had almost no control over their Gift. Visions either arrived or they didn’t. Dream or trance precogs were less rare, but accuracy varied enormously because so often the dreams, voices, automatic writing, or symbolic images required interpretation.

Ruben’s form of precognition was by far the most common—a simple, quiet knowing that arrived without fanfare and almost always concerned the near future. It was also generally the least accurate. “Hunch” precogs could easily mistake their own thoughts or projections for the working of their Gift. At least half the time, and usually more, that’s what happened.

But not with him. Ruben always knew the difference. He didn’t understand why others didn’t. Sometimes the information his Gift provided was so muddled as to be useless—the specifics of the future were wonderfully malleable when a patterner wasn’t meddling with the present—but he could always tell the difference between knowing and eavesdropping on the noise in his own head.

Two things were common to all precogs, however. They all occasionally experienced a different form of their Gift. A trance precog might have a strong hunch, or a huncher have a true dream. And—for reasons that were often debated, never proven—they were usually blind to their own futures.

Usually. Not always.

Behind him, his lady, the love of his life, rolled onto her back and began to snore softly.

Love and sorrow rose and swirled in him, leaving him giddy and filled with tears. He was alive now . Now was the time that truly mattered . . . an odd concept for a precog, he supposed, but true. He couldn’t act, think, feel in the future or in the past. Only in this moment.

Was it terribly selfish of him to hold tight to this one secret? Probably. He had told one person about his recurring dream—his second-in-command in the Shadow Unit. But not Deb. Not his beautiful, wondrous Deb.

Twenty years ago Deb had asked him if he’d ever seen his own death. They’d just been dating then, but he’d known he would ask her to marry him. That hadn’t been precognition, but the soaring dream of his heart. He’d told her “no” back then, quite truthfully . . . but added that if he ever did, he would tell no one. Not even her. Ruben marveled that his younger self—so often wrong about so much—had been so nearly right about that.

He’d had the practical discussions with her. Given his heart attack, that had been necessary. But those discussions came with a large and lustrous “if.” He couldn’t take that “if” away from her, though he knew it was wrong.

Four times now he’d dreamed of pain, terrible pain, the kind that eats thoughts and strength and life. He never remembered much about the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher