![Pow!]()

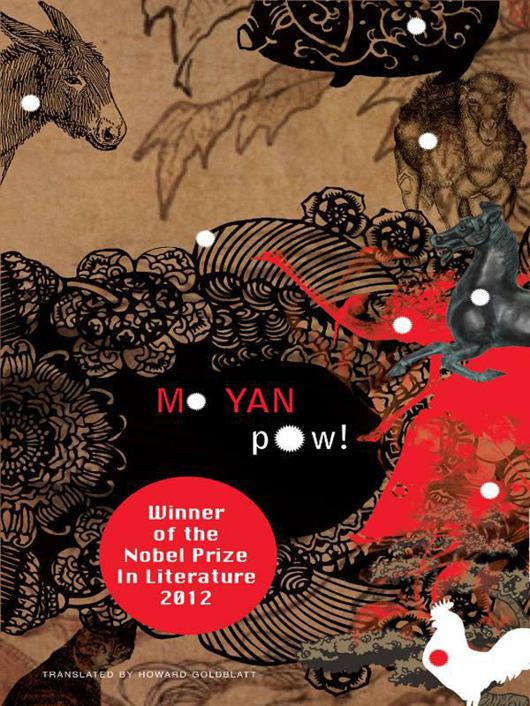

Pow!

a bin against the wall and laughed heartily. ‘You are very discriminating, worthy Nephew!’

POW! 27

Tongue stiff, cheeks numb, eyes dull and heavy, one yawn after another. I fight to keep going, muddling along with my tale…a car horn startles me awake. Morning sunlight streams into the temple; there's bat guano on the floor. An ambiguous smile adorns the little, basin-like face of the Meat God; just looking at it gives me a sense of pride, mixed with remorse and trepidation. My past is a fairy tale or, more accurately, a big lie. I stare at him, he stares back, lively and expressive, almost as if he's about to speak to me. I feel as if I could animate him with a single puff of air, send him running happily out of the temple over to the feast and the meat forum to eat his fill and join the discussion. If the Meat God is really anything like me, then he's someone who can talk and talk and talk. Wise Monk continues to sit, lotus position, on his rush mat, unchanged. He casts a meaningful look at me before shutting his eyes. I recall my sleep being interrupted by pangs of hunger in the middle of the night, but when I awoke this morning I wasn't hungry at all. I'm now reminded of how, I think, the woman who resembles Aunty Wild Mule nourished me with her spurting milk. I lick my lips and detect its sweet taste again. This is the second day of the Carnivore Festival, when forums and discussion groups on a variety of topics will take place in guest houses and restaurants in the twin cities, followed by all manner of banquets. Barbecue stands will continue in operation in the field across the temple, albeit with a new batch of cooks. At the moment, none of them and no prospective customers have arrived. No one but fast-moving cleanup crews are up and working at this hour, busy as battlefield mop-up units.

My parents sent me to school soon after New Year's, not the normal time to begin. But, thanks to Lao Lan's intervention, the authorities were happy to let me enrol. They also enrolled my sister in the Early Red Academy, or, as it's called now, preschool.

The school gate was just outside the village, a hundred metres on the other side of Hanlin Bridge. The one-time manor of the Lan family, it had fallen into a state of rot and disrepair. The buildings, with green brick walls and blue tiled roofs, had once heralded the glories of the Lan family to all who laid eyes on them. Locally, the Lans were not thought of as rustic rich. Members of Lao Lan's father's generation had studied in America, which gave him something to be proud of. Four metal characters in red——that spelt out ‘Hanlin Primary School’ were welded onto the cast-iron arch spanning the gate. Already eleven, I was placed in the first grade, which made me nearly twice the age of, and a head taller than, my classmates. I was the centre of attention for students and teachers alike during the morning flag-raising ceremony, and I'll bet they thought that a boy from one of the upper classes had mistakenly lined up with them.

I was not cut out to be a student. It was sheer agony to sit on a stool for forty-five minutes and behave myself. And not just once a day, but seven times, four in the morning and three in the afternoon. I began to feel dizzy at about the ten-minute mark and wanted nothing more than to lie down and go to sleep. I could hear neither my teacher's murmurs nor my classmates’ recitations. The teacher's face faded from view and was replaced by what looked like a cinema screen across which danced images of people, cows and dogs.

My homeroom teacher, Ms Cai, a woman with a moon face, a head of hair like a rat's nest, a short neck and a big arse—she waddled like a duck—hated me from the beginning but chose to ignore me. She taught maths, which invariably put me to sleep. ‘Luo Xiaotong!’ she shouted once, grabbing me by the ear.

Eyes open but brain not yet in gear, I asked: ‘What's wrong? Someone die at your house?’

If she interpreted that as a curse that augured a death in her family, she was wrong. I'd been dreaming of doctors in white smocks running down the street shouting: ‘Hurry, hurry, hurry, someone's died at the teacher's house.’ But, of course, she couldn't know that, which is why she interpreted my shout as a curse on her. If I'd said that to one of the less civilized teachers at the school, my ears would have been ringing from a resounding slap. But she was a cultured woman; she merely returned to the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher