![Praying for Sleep]()

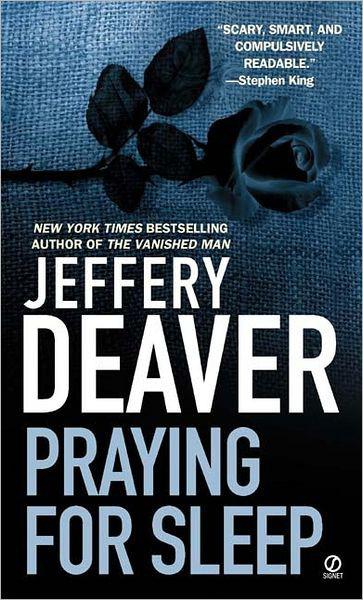

Praying for Sleep

say.

“You’ve said a couple of times now, Michael, that you’re worried about what’s ‘ahead.’ Do you mean your immediate future?”

“I never said that,” he snapped.

“Did you mean something ahead of you in the hallway? Was someone upsetting you?”

“I never said a word like that. Someone’s making up things about me. The government’s usually to blame, the fuckers. I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Do you mean ‘a head,’ like someone’s head, a skull?”

He blinked and muttered, “I can’t go into it.”

“If it’s not the head maybe you mean someone’s face? Whose?”

“I can’t fucking go into it! You’re going to have to use truth serum on me if you want that information. I’ll bet you have already. You may know that as scopolamine.” He fell silent, a smirk upon his face.

The therapy was no more sophisticated than this. Like Kohler, Anne Muller never tried to dissuade Michael of his delusions. She dug into them, trying to learn what was inside her patient. He resisted with the resilience of a captured spy.

But after four months Michael’s paranoid and contrary nature suddenly vanished. Muller herself grew suspicious—she’d come to recognize that Michael had a calculating streak in him. He grew increasingly cheerful and giddy. Then she learned from the orderlies that he’d taken to stealing clothes from the laundry room. She assumed that his apparently improved temperament was a ruse to shift suspicion about the theft.

Yet before Muller could confront him, Michael began to deliver the loot to her. First, two mismatched socks. He handed them to her with the bashful smile of a boy with a crush. She returned the articles to their owners and told Michael not to steal anymore. He grew very grave and told her he was “unable at this time to make a commitment of that magnitude.”

Important principles were involved, he continued. “Very important.”

Apparently so, for the next week, she received five T-shirts and more socks. “I’m giving these clothes to you,” he announced in a whisper, then walked away abruptly as if late for a train. The gift-giving went on for several weeks. Muller was far less concerned about the thefts themselves than understanding what Michael’s behavior meant.

Then, when she was lying in bed at three in the morning, the epiphany occurred. She sat up, stunned.

In the course of a long, disjointed therapy session that day, Michael had lowered his voice and, eyes averted, whispered, “The reason is, I want to get my clothes to you. Don’t tell anyone. It’s very risky. You have no idea how risky.”

Clothes to you. Close to you. I want to get close to you. Muller bolted from her bed and drove immediately to her office, where she dictated a lengthy report that began with a subdued introduction tantamount to a psychiatrist’s shout of joy:

Major breakthrough yesterday. Pt. expressed desire for emotional connection with Dr., accompanied by animated affect.

As the treatment continued, Michael’s paranoia diminished further. The thefts stopped. He grew more sociable and cheerful and he required less medication than before. He enjoyed his group-therapy sessions and looked forward to outings that had previously terrified him. He started doing chores around the hospital, helping out the library and gardening staffs. Michael, Muller reported, had even driven her car several times.

Kohler now looked up from the report and gazed across the gritty parking lot. Lightning flashed in the west. Then he read the final entry in the file, written in a hand other than Anne Muller’s. He found he could picture the scene upon which these notes were based only too well:

Michael lies on his bed, looking through a history book, when a doctor comes into his room. He sits on the bed and smiles at the patient, inquiring about the book. Michael immediately stiffens. Little sparks of his paranoia begin to burn.

“Who’re you, what do you want?”

“I’m Dr. Klein. . . . Michael, I’m afraid I have to tell you that Dr. Muller is sick.”

“Sick? Dr. Anne is sick?”

“I’m afraid she’s not going to be meeting with you.”

Michael doesn’t know what to say. “Tomorrow?” he manages to blurt, wondering what this man has done with his doctor and friend. “Will I see her tomorrow?”

“No, she’s not coming back to the hospital.”

“She left me?”

“Actually, Michael, she didn’t leave you. She left all of us. She passed away

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher