![Ptolemy's Gate]()

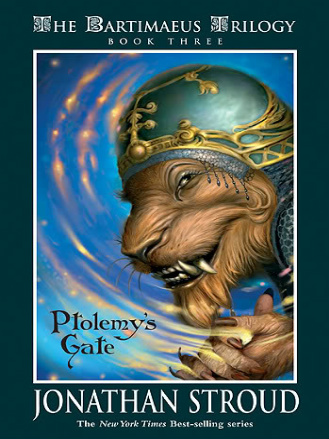

Ptolemy's Gate

normal safeguards are there to restrict movement—you know, keep the djinni out, keep us secure. I want the opposite effect; I want to be able to move freely. So if I do this" —with a deliberate toe, he smudged the cochineal line that marked the perimeter of the circle—"that should allow my spirit to depart. Through that little hole. My body shall remain here."

I frowned. "Why use the pentacle at all?"

"Aha. Good point. According to our friend Affa, the shamans of distant regions, who converse with djinn on the borders of our realms, speak certain words and leave their bodies at will. They do not use circles. But they are not trying to pass through the boundaries between our worlds—those elemental walls you have told me so much about. And I am. I think that, just as the circle's power pulls you directly to me when I summon you, so the same circle can propel me in the opposite direction, through the walls, when the words are reversed. It is a focusing mechanism. You understand?"

I scratched my chin. "Erm. . . Sorry, what did Affa say again?"

My master raised his eyes to the heavens. "It doesn't matter. But this bit does. I think I can reverse the normal summons easily enough, but if a gate does open up, I need something on the other side to guide me safely through. Something that provides a destination."

"That's a problem," I said. "There are no 'destinations' in the Other Place. No mountains, no forests. I've told you that countless times."

"I know. That's where you come in." The boy was crouching on the floor, rummaging through a pile of the usual magical paraphernalia that every Egyptian magician accumulated: scarabs, mummified rodents, novelty pyramids, the lot. He held up a small ankh[4] and thrust it in my direction. "Think this is iron?"

[4] Ankh: a kind of amulet, T-shaped, with a loop at the top. Symbol of life. In pharaonic Egypt, when magic was commonplace, many ankhs contained trapped entities and were powerful protectors. By Ptolemy's time they were usually symbolic only. But iron, like silver, always repels the djinn.

A waft of essence-stinging cold; I leaned back irritably. "Yep. Stop waving it about."

"Good. I'll keep this on my body for protection. Just in case any imps come calling while I'm gone. Now, back to you. Rekhyt, I thank you for all the services you have done me; I am in your debt. In a moment I shall dismiss you. Your obligation to me, such as it is, will be at an end."

I bowed in the customary way. "My thanks, master."

He waved his hand. "Forget that master business now. When you are in the Other Place, listen out for your name—your true one, I mean.[5] When I have finished my incantation, I shall call your name three times. If you wish, you may answer me: I believe that will be enough to provide the destination that I need. I shall pass through the gate to you."

[5] Bartimaeus, this was. Thought you might have forgotten. Ptolemy never used it, for politeness' sake.

I looked dubious in that way I have. "You reckon?"

"I do."The boy smiled at me. "Rekhyt, if you are sick of the sight of me after all this time, the solution is simple. Do not respond to my call."

"It's up to me?"

"Of course. The Other Place is your domain. If you do see fit to call me over, I shall be most honored." His face was flushed with excitement, his pupils dilated like a cat's; in his mind he was already tasting the wonders of the other side. I watched his movements as he went over to a bowl beside the window. It contained water. He washed his face and neck.

"Your theories are all very well," I ventured, "but have they told you what will happen to your body if you pass across? You are not a creature of essence."

He dried himself on a cloth, looking out over the rooftops, where the commotion and bustle of midday hung like an invisible pall upon the city. "Sometimes," he murmured, "I feel I am not a creature of Earth, either. All my life has been shut away in libraries, never experiencing the sensations of the world. When I come back, Rekhyt, I shall wander afar like you have done. . ." He turned and stretched his thin brown arms. "You are right, of course: I don't know what will happen. Perhaps I will suffer for it. But it is worth the risk, I think, to see what no other man has seen!" He stepped across and closed the shutters on the window, shrouding us both in dim, pale light. Next he locked the chamber door.

"Perhaps," I said, "you will find yourself in my power, when we meet

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher