![Ptolemy's Gate]()

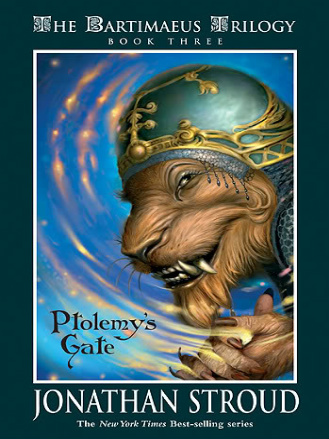

Ptolemy's Gate

holding it between finger and thumb by its shining, gleaming tip. It quivered once, twice. He was gauging the range here—he'd never missed a target yet, from Carthage to old Colchis. Every knife he'd thrown had found its throat.

His wrist flickered; the silver arc of the knifes flight cut the air in two. It landed with a soft noise, hilt-deep in the cushion, an inch from the child's neck.

The assassin paused in doubt, still crouched upon the sill. The back of his hands bore the crisscross scars that marked him as an adept of the dark academy. An adept never missed his target. The throw had been exact, precisely calibrated. . . yet it had missed. Had the victim moved a crucial fraction? Impossible— the boy was fast asleep. From his person he pulled a second dagger.[4] Another careful aim (the assassin was conscious of his brothers behind and below him on the wall: he felt the grim weight of their impatience). A flick of the wrist, a momentary arc—

[4] I won't say where he pulled it from. Let's just say that the knife had hygiene issues as well as being quite sharp.

With a soft noise, the second dagger landed in the cushion, an inch to the other side of the prince's neck. As he slept, perhaps he dreamed—a smile twitched ghostlike at the corners of his mouth.

Behind the black gauze of the scarf that masked his face, the assassin frowned. From within his tunic he drew a strip of fabric, twined tightly into a cord. In seven years since the Hermit had ordered his first kill, his garrote had never snapped, his hands had never failed him.With leopard's stealth, he slid from the sill and stole across the moonlit floor.

[5] The Hermit of the Mountain trained his followers in numerous methods of foolproof murder. They could use garrotes, swords, knives, batons, ropes, poisons, discs, bolas, pellets, and arrows inimitably, as well as being pretty handy with the evil eye. Death by fingertip and toe-flex was also taught, and the furtive nip was a specialty. Stomach-threads and tapeworms were available for advanced students. And the best of it was that it was all guilt-free: each assassination was justified and condoned by a powerful religious disregard for the sanctity of other people's lives.

In his bed the boy murmured something. He stirred beneath his sheet. The assassin froze rigid, a black statue in the center of the room.

Behind, at the window, two of his companions insinuated themselves upon the sill. They waited, watching.

The boy gave a little sigh and fell silent once more. He lay faceup among his cushions, a dagger's hilt protruding on either side.

Seven seconds passed. The assassin moved again. He stole around behind the cushions, looping the ends of the cord around his hands. Now he was directly above the child; he bent swiftly, set the cord upon the sleeping throat—

The boy's eyes opened. He reached up a hand, grasped the assassin's left wrist and, without exertion, swung him headfirst into the nearest wall, snapping his neck like a reed stalk. He flung off his silken sheet and, with a bound, stood free, facing the window.

Up on the sill, silhouetted against the moon, two assassins hissed like rock snakes. Their comrade's death was an affront to their collective pride. One plucked from his robe a pipe of bone; from a cavity between his teeth he sucked a pellet, eggshell thin, filled with poison. He set the pipe to his lips, blew once: the pellet shot across the room, directed at the child's heart.

The boy gave a skip; the pellet shattered against a pillar, spattering it with liquid. A plume of green vapor drizzled through the air.

The two assassins leaped into the room; one this way, the other that. Each now held a scimitar in his hand; they spun them in complex flourishes about their heads, dark eyes scanning the room.

The boy was gone. The room was still. Green poison nibbled at the pillar; the stones fizzed with it.

Never once in seven years, from Antioch to Pergamum, had these assassins lost a victim.[6] Their arms stopped moving; they slowed their pace, listening intently, tasting the air for the taint of fear.

[6] And they didn't intend to start now. The Hermit was known to be pretty sniffy about disciples who returned in failure. There was a wall of the institute layered with their skins—an ingenious display that encouraged vigor in his students, as well as nicely keeping out the drafts.

From behind a pillar in the center of the room came the faintest scuffling, like a mouse

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher