![Ptolemy's Gate]()

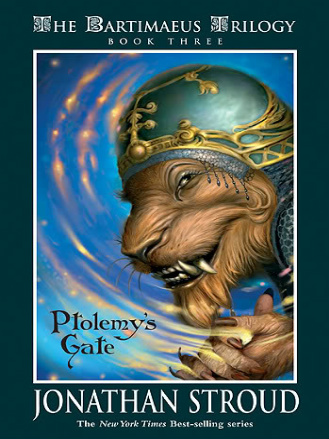

Ptolemy's Gate

a few days of training they sailed for America on special troopships.

Months passed; the expected return of the conquering heroes did not materialize. Everything went quiet. Information from the colonies was hard to come by; government statements became elusive. At length rumors began, perhaps spread by traders operating across the Atlantic: the army was bogged down deep in enemy territory; two battalions had been massacred; many men were dead, some had fled into the trackless forests and had never been seen again. There was talk of starvation and other horrors. The recruitment office queues dwindled and died away; a sullenness stole imperceptibly across the faces of people in the London streets.

In due course passive resentment turned to action. It began with a few disjointed episodes, far-flung and brief, each of which could be ascribed to random local causes. In one town a mother conducted a solitary protest, hurling a rock through the window of a recruitment office; in another, a group of laborers set down their tools and refused to toil for their daily pittance. Three merchants tipped a truckload of precious goods— golden oats, fine flour, sun-cured hams—upon the Whitehall road and, dousing it with oil, ignited it, sending a fragile ribbon of smoke into the sky. A minor magician from the eastern colonies, perhaps maddened by years of foreign diet, ran screaming into the War Ministry with an elemental sphere in his hand; in seconds he had activated the sphere, destroying himself and two young receptionists in a maelstrom of raging air.

While none of the incidents was as dramatic as the attacks once carried out by the traitor Duvall, or even by the moribund Resistance, they had greater staying power in the public mind. Despite the best efforts of Mr. Mandrake at the Information Ministry, they were discussed repeatedly in markets, at workplaces, in pubs and cafes, until by the strange alchemy of gossip and rumor they were joined together into one big story, becoming the symptoms of a collective protest against the magicians' rule.

But it was a protest without teeth, and Kitty, who had tried active rebellion in her time, was under no illusions about how it was going to end. Each evening, at work in the Frog Inn, she heard proposals of strikes and demonstrations, but no suggestion of how to prevent the magicians' demons from cracking down. Yes, a few scattered individuals had resilience, as she had, but that alone was not enough. Allies were needed too.

The bus set her down in a peaceful, leafy road south of Oxford Street. Shouldering her bag, she walked the last two blocks to the London Library.

The guard had seen her often, both singly and in the company of Mr. Button. Nevertheless, he ignored her greeting, held out his hand for her pass, and scanned it sourly from his perch on a high stool behind a desk. Without comment, he ushered her on. Kitty smiled sweetly and strolled into the library foyer.

The library filled five labyrinthine floors, extending across the width of three town houses in the corner of a quiet square. Although out of bounds to commoners, it was not primarily concerned with magical texts, but instead with works that the authorities considered dangerous or subversive in the wrong hands. These included books on history, on mathematics, astronomy and other stagnant sciences, as well as literature that had been forbidden since Gladstone's day. Few of the leading magicians had the time or inclination to visit it, but Mr. Button, from whose attentions few historical texts were safe, sent Kitty to browse there frequently.

As usual, the library was almost deserted. Looking into the alcoves stretching away from the marbled stairs, Kitty made out one or two elderly gentlemen, sitting crumpled below the windows in the apricot afternoon light. One held a newspaper loosely in his hands; another definitely slept. Along a distant aisle a young -woman was sweeping the floor; shht, shht, shht went the broom, and faint clouds of dust seeped through the shelving to the aisles on either side.

Kitty had a list of titles to borrow on Mr. Button's behalf, but she also had an agenda of her own. After two years' regular visits, she knew her way around; before long she was in a secluded corridor on the second floor, standing in front of the Demonology section.

Necho, Rekhyt . . . Her knowledge of ancient languages was nonexistent: these names might belong in almost any culture. Babylonian? Assyrian? On a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher