![Shadows and Light]()

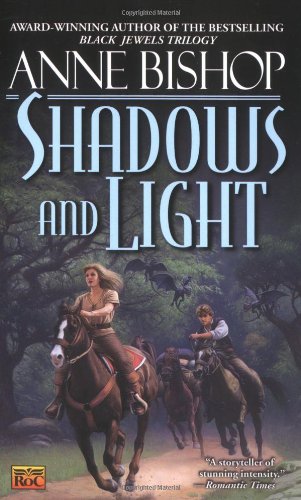

Shadows and Light

notes. “We have to talk, and this is the best way to do that privately.”

“All right.” She shifted a little. “Let me light a few more candles. This one isn’t enough.”

“Don’t,” Aiden said, his head bent over the harp. “Sometimes things are said more easily in the dark.”

Morag shifted again. One candle made the room too dark, too intimate. Enough light for lovers, but not for friends. Because it was Aiden, she stayed where she was.

He said nothing. Just played idle notes on his harp. It was like listening to the summer leaves stirred by a soft breeze or the trickle of water in a fountain. Her body began to relax into the sound until she was drifting in some easy place where her mind was at rest.

“Tonight,” Aiden said softly, “what did you mean when you said, ”They’re the Fae‘?“

She drifted with the harp’s notes. He was right. It was easier to say some things in the dark. “They still are what the rest of us used to be, what we’ve forgotten how to be. They’re the Fae. They’ve never forgotten their place in the world, never forgotten that there is death as well as life, shadows as well as light. For them, Tir Alainn is a sanctuary, a place to rest. But they never left the world, and the rest of us have become a pale reflection of what we used to be.”

“You’re being too harsh.”

“Am I? If the Inquisitors had come to the west instead of the eastern part of Sylvalan, the first witch they caught still would have died. But not the second one, not any of the others after that. It wouldn’t have mattered what the barons or the gentry or any other human said, the Fae in the west would have stopped it. What does that say about the rest of us?”

Aiden sighed. “I don’t know, Morag. I don’t know if the rest of the Fae will pay any more attention to Ashk than they did to you or me.”

“Then I pity them.”

Aiden stopped playing and looked at her. “Why feel pity for them?”

“Because the Hunter will have none.”

Ashk lay curled against Padrick’s side, her head resting on his shoulder. His lovemaking tonight had ranged from fierce to tender and back again, demanding enough to make her forget everything but him.

But they needed to talk, and she couldn’t push it aside any longer.

“Padrick...”

He turned his head, pressed his lips against her forehead. “I want to say something first. Then I’ll listen to whatever you have to tell me.”

Her heart stuttered. Found its rhythm again. “All right.”

He sighed. Shifted a little to draw her closer. “I fell in love with you the night I met you, and I wanted you in my life in every way you would let me have you. But I was a gentry baron, and I needed the legal contract of a human marriage so that my children could inherit my estate and other property, and my male heir could become the next baron. Because that was a human need, I followed human custom, which is usually to ask a woman’s father for permission to broach the question of marriage. You’d never mentioned your father. Never talked about your family at all. Except for your grandfather.

“I went riding in the woods one afternoon, trying to think of a way to ask you where to find him without telling you why I wanted to find him. Suddenly there was a stag standing in the middle of the trail. He stared at me for a long moment, then turned and walked down the trail. I followed him to a meadow, and he changed into a man.”

“Kernos,” Ashk said softly.

“Kernos,” Padrick agreed. “The old Lord of the Woods. If he’d been an old baron, I would have known exactly what to say, but he looked at me with those eyes that had seen so much, knew so much, and I started stammering like some foolish schoolboy. He cut me off just by raising his hand. And he told me that life has its seasons, just like the woods. He said we would have a green season, a time when life would swell and grow, and he hoped it would be a long season in our lives, one that lasted many years.

But the day would come when the world needed the Hunter and the green season of our lives would give way to the next—and when that day came, I would have to let you go. He told me I needed to be sure that I could let you go, and if I couldn’t, then he wouldn’t interfere with my being your lover but he would never consent to your being my wife.”

“But you did ask me to be your wife, and he stood with me when the magistrate spoke the words for the human ceremony.” Ashk

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher