![Shadows and Light]()

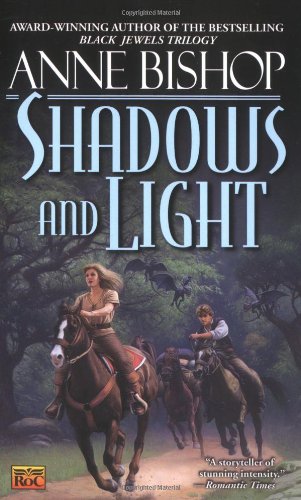

Shadows and Light

song.

The third song was one he’d never heard before, and he found himself leaning forward to catch the words and the tune, almost grinding his teeth when the singer kept faltering. It wasn’t until Lyrra slid over and gave him a hard jab with her elbow that he realized it was his own intense stare that was unnerving the singer. He lowered his eyes and, with effort, kept himself from leaping up and demanding that she sing it again. There was time. He’d corner her later.

After the musicians, Skelly stood up and told a story about his sweet granny, who was, apparently, the stern woman sitting on the other side of the square with her hands folded and her hair scraped back into a bun that must have made her scalp ache. It made Aiden’s scalp ache just looking at her. And the expression on her face was fierce enough to frighten any rational man.

Obviously, Skelly wasn’t a rational man, because he continued his story, gesturing now and then toward his sweet granny. When he finally got to the punch line, the first person to burst out laughing was his granny. The laughter transformed her face, and her eyes sparkled with mischief. As she pulled the pins out of her hair, she said, “Ah, Skelly. That story gets worse every time you tell it.”

Aiden heard Lyrra’s soft grunt, and he knew she, too, had taken the bait without realizing there was a hook in it. Seeing the grins on the villagers’ faces and how the old woman now looked like a sweet granny, he understood that the scraped-back hair and the fierce expression were props for Skelly’s story. Something he was sure everyone else in the village had known.

Then the boy came up with his small harp. After bowing to Aiden and Lyrra, he sat on the small bench Skelly brought over for him, settled himself, and began to play a song he wrote himself.

The boy had potential. Aiden felt his Bard’s gift swell with the desire to kindle that spark until it burned brightly.

The song, on other hand ...

When the boy finished, he lowered his head. The applause from the crowd was more a response to his courage than an indication of pleasure.

Then the boy raised his head, looked Aiden in the eyes, and said, “It’s not a good song.”

“No, it isn’t,” Aiden replied gently. “But it is a good first effort. With time and practice, you’ll write better songs.” He reached for his harp.

“Aiden,” Lyrra whispered fiercely. “You can’t play the harp yet. Your fingers aren’t healed.”

“They’re healed well enough for this song.” He set his fingers on the strings, suppressed a wince, plucked the first chord, and sang.

He watched the boy’s eyes widen in disbelief and disappointment—and something close to hope. He watched the adult faces in the crowd settle into a painfully polite expression. And he knew by the look on Lyrra’s face that she would, at that moment, gladly deny knowing him.

It was, if one wanted to be kind, a bad song. And he sang all five verses and their refrains.

When he was done, he handed the harp to Lyrra, flexed his painfully sore hands, and smiled at the boy. “

That was the first song I ever wrote. I was about your age. But with time and practice, I’ve gotten a bit better.” He took a breath and began to sing “The Green Hills of Home.” It was a song about a traveler, alone and lonely, yearning for a place far away. It was a song about a man, alone and lonely, yearning for the lover who wasn’t there. He’d written it over the winter, when he’d been traveling and Lyrra had been at Bright-wood.

Her voice joined his, harmonizing. She didn’t even try to play the harp, so there was nothing but their voices, filled with the same remembered yearning.

When the last note faded, he watched people brush away tears—and felt the sting of tears in his own eyes.

Lyrra began plucking a simple tune on the harp, something that had no words. Aiden chose one of the whistles and joined her, letting the song flow through him. They used it as a transition song, when the audience needed time to settle again. Then he sang the song about the Black Coats—and watched the adult faces turn grim. Lyrra followed it with the poem about witches that he’d set to music. After that, they did a few romantic songs, gradually moving toward songs that were lighter and humorous. By the time they got to “The Mouse Song,” people were grinning and stifling chuckles— but a lot of them seemed to be watching something over Aiden’s

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher