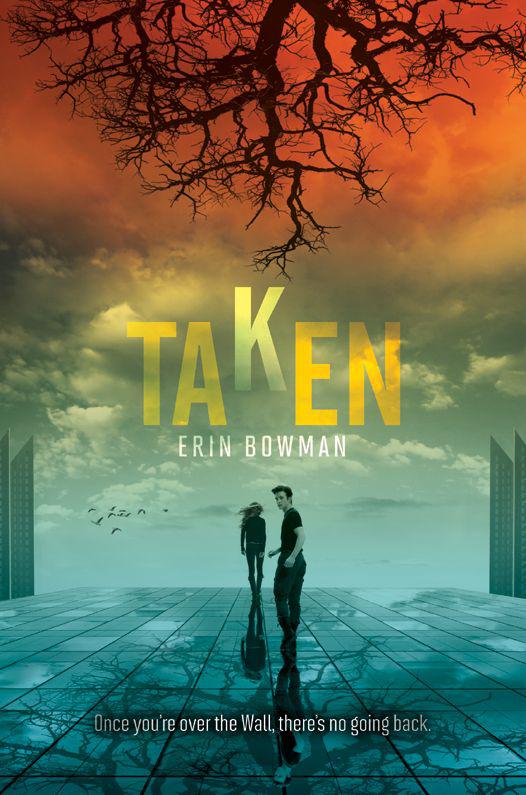

![Taken (Erin Bowman)]()

Taken (Erin Bowman)

move behind her, hold her bow hand in mine and wrap my other arm around her so that I, too, am grasping the string.

“Now focus,” I say. “Nothing exists in the world except for the target.” I drop my arms and step away from her. She lets the arrow fly, and this time it strikes true. It barely manages to hang on to the outermost ring, but nonetheless, it is there.

She jumps in excitement, turning to face me. “Did you see that?”

“Course I did. I’m standing right here.”

She nocks another arrow and reaims. I watch her muscles clench as she focuses, admire how her eyes narrow. I wonder how she hasn’t caught me staring at her like this, not even once since we started hanging out. Perhaps archery has been a worthy distraction.

Emma releases her bowstring. This time she does much better, missing the bull’s-eye by only a single ring.

With a triumphant yelp she throws her arms around my neck and hugs me. It takes me by surprise. She feels small in my arms, even though she never seems small in person. When she breaks away, I can see how truly proud she is.

“I think you’re a natural,” I tell her.

“I think you’re a good teacher.”

“No, seriously. Teaching and correcting form can only do so much. The rest is either in a person or it’s not.”

She walks up to the target, twists the arrows free, and returns them to her quiver. “Let’s have a match,” she says.

“You really think you can beat me after hitting a target twice?” I ask skeptically.

“Oh, come on. Let’s play. Besides, I’m not the one that challenged you to a match that day back at the lake.”

I smirk. “Fine, have it your way. Just don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

And with that, we play, shooting three arrows from twenty paces, then three more from forty, and then a final set at sixty. Emma does extremely well at twenty paces, but her arrows start to stray at forty. From the farthest distance she misses entirely, all three arrows landing in the soft ground around the target. I shoot a perfect game without even trying. We retrieve our arrows and then sit down in the grass, our foreheads lined with sweat.

“Okay, you’re right,” Emma admits. “When it comes to shooting, you can absolutely crush me.”

“Told you.” I take a swig from my waterskin and then pass it to her. I watch as a bead of sweat trickles down her neck and across her collarbone, disappearing beyond the neckline of her shirt.

“If I tell you something, do you promise to not repeat it?” she asks, handing the water back to me.

“Sure.”

“Have you ever read the scrolls from the library that document the beginnings of this place?”

“The history of Claysoot? Yeah, I’ve read them.”

“Don’t you find them odd?”

“How so?”

“For starters, their memories were so shoddy after the storm destroyed Claysoot. They remembered certain skills—like how to tend crops and work a loom and rebuild collapsed buildings—but they forgot the names of their neighbors. And their own town. And anything they might have been doing before the weather hit. How does something like that happen? And where were their parents? The scrolls don’t mention having to bury the deceased, and if the adults weren’t lost to the storm, it means they weren’t here when it rolled in.”

“So you think their parents were somewhere else?” I ask, taken aback by the idea.

“Maybe? I don’t know. The children must have been born in Claysoot, to mothers that were living here also, because nothing can cross the Wall and live to tell the tale. But at the same time, it seems very unlikely that every single mother died in a storm that small children survived.”

I’ve never thought of it this way, but she has a point.

“It’s unlikely,” I say, echoing her. “But possible.”

She wrinkles her forehead. “It still feels off.”

“We’ll never really know, I guess. The scrolls could be incomplete or poorly written. They could have left out burying the adults because it was too difficult to write.”

“Yeah, maybe,” she says, but I can sense the doubt in her voice. Emma’s questions remind me of Ma’s letter and her mention of how mysterious life is. Like my mother, Emma is obsessed with inexplicable details.

I take another swig of the water. It’s warm now, but it’s still nice to wet my lips.

“So why can’t I repeat any of this?” I ask.

“You know how the Council freaks out every time someone suggests there’s something

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher