![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

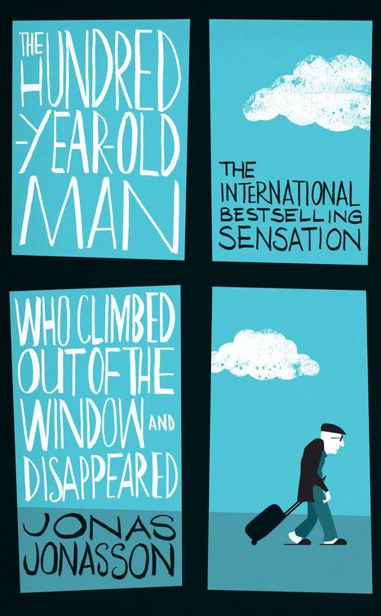

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

hard-line attitude towards the popular dissatisfaction did indeed lead to the country grinding to a halt. Millions of Frenchmen went on strike. The docks in Marseilles closed down, as did international airports, the railway, and all department stores.

The distribution of gas and oil came to a halt and rubbish collection stopped. From every side there were workers’ demands. For higher wages, of course, and shorter working hours, and better job security, and more influence.

But in addition there were demands for a new system of education. And a new society! The Fifth Republic was threatened.

Hundreds of thousands of Frenchmen demonstrated in the streets, and it wasn’t always peaceful either. Cars were set on fire, trees were felled, streets were dug up, barricades were built… There were gendarmes, riot police, teargas and shields…

That was when the French president, the prime minister and his government did a quick about-turn. Interior Minister Fouchet’s special advisor no longer had any influence (he was imprisoned secretly in the premises of the secret police where he had considerable difficulty in explaining why he had a radio transmitter installed in his bathroom scales). The workers on general strike were suddenly offered a big increase in the minimum wage, a general increase of wages of ten per cent, a three-hour reduction of the working week, increased family allowances, more trade union power, negotiations on comprehensive general wage agreements and inflation-adjusted wages. A couple of the government’s ministers had to resign too, among them Interior Minister Fouchet.

With this array of measures, the government and president neutralized the most revolutionary factions. There was no popular support to take things further than they had already gone. Workers went back to work, occupations stopped, shops opened again, the transport sector began to function. May 1968 had now become June 1968. And the Fifth Republic was still there.

President Charles de Gaulle personally phoned the Indonesian Embassy in Paris and asked for Mr Allan Karlsson, in order to award him a medal. But at the embassy they said that Allan Karlsson no longer worked there and nobody, including the ambassador herself, could say where he had gone.

Chapter 24

Thursday, 26th May 2005

Prosecutor Ranelid had to try to salvage what could be saved of his career and honour. He arranged a press conference that same afternoon to say that he had just cancelled the warrant for the arrest of the three men and the woman in the case of the disappearing centenarian.

Prosecutor Ranelid was good at lots of things, but not at admitting his shortcomings and his mistakes. The prosecutor turned and twisted in his explanation, which consisted of the information that while Allan Karlsson and his friends were not under arrest (they had, incidentally, been found that same afternoon in Västergötland), they were probably guilty anyway, that the prosecutor had acted properly, and that the only thing that was new was that the evidence had changed so dramatically that the arrest warrants for the time being were no longer valid.

The representatives of the media wondered in what way the proof had changed, and Prosecutor Ranelid described in detail the new information from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with regard to the fate of Bylund and Hultén in Djibouti and Riga respectively. And then Ranelid finished by saying that the law sometimes required that arrest warrants be withdrawn, however offensive that may feel in certain cases.

Prosecutor Ranelid sensed that he had not closed the matter entirely. And that impression was immediately confirmed when the representative of the major national Dagens Nyheter peered over his reading glasses and reeled off a monologue containing a host of questions that made the prosecutor especially uneasy.

‘Have I understood correctly that despite the new circumstances you still consider Allan Karlsson guilty of murder ormanslaughter? Does that mean that you believe that Allan Karlsson, one hundred years old as we know, has forced the thirty-two-year-old Bengt Bylund to follow him to Djibouti on the Horn of Africa and there blown the said Bylund – but not himself – to bits as recently as yesterday afternoon, and then in all haste gone to Västergötland? Can you describe what means of transport Karlsson is meant to have used, considering that to the best of my knowledge there are no direct flights between Djibouti

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher