![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

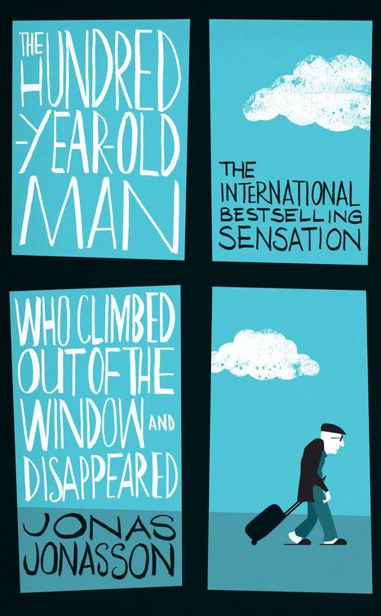

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

Union.

‘Don’t worry, my dear Yury Borisovich, Mr Karlsson won’t die. At least not yet.’

Marshal Beria explained that he intended to keep Allan Karlsson out of the way as a backup, in case Yury Borisovich and his fellow scientists continued to fail to make a bomb. This explanation had an inbuilt threat, and Marshal Beria was very pleased with that.

While waiting for his trial, Allan sat in one of the many cells at the headquarters of the secret police. The only thing that happened was that every day Allan was served a loaf of bread, thirty grams of sugar and three warm meals (vegetable soup, vegetable soup and vegetable soup).

The food had been decidedly better in the Kremlin than it was here in the cell. But Allan thought that although the soup tasted as it did, he could at least enjoy it in peace, without anyone shouting at him for reasons that he couldn’t quite follow.

This new diet lasted six days, before the special tribunal of the secret police summoned Allan. The courtroom, just like Allan’s cell, was in the enormous secret police headquarters beside Lubyanka Square, but a few floors higher up. Allan was placed on a chair in front of a judge behind a pulpit. To the left of the judge sat the prosecutor, a man with a grim expression, and to the right Allan’s defence lawyer, a man with an equally grim expression.

For starters, the prosecutor said something in Russian that Allan didn’t understand. Then the defence lawyer said something else in Russian that Allan didn’t understand either. After which the judge nodded as if he was thinking, before opening and reading a little crib (to make sure he got it right) and then proclaiming the verdict of the court:

‘The special tribunal hereby condemns Allan Emmanuel Karlsson, citizen of the kingdom of Sweden, as an element dangerous to the Soviet socialist society, to a sentence of thirty years in the correction camp in Vladivostok.’

The judge informed the convicted man that the sentence could be appealed, and that the appeal could take place within three months of the present day. But Allan Karlsson’s defence lawyer informed the court on behalf of Allan Karlsson that they would not be appealing. Allan Karlsson was, on the contrary, grateful for the mild sentence.

Allan was of course never asked whether or not he was grateful, but the verdict did undoubtedly have some good aspects. First, the accused would live, which was rare when you had been classified as a dangerous element. And second, he would be going to the Gulag camps in Vladivostok, which had the most bearable climate in Siberia. The weather there wasn’t much more unpleasant than back home in Södermanland, while further north and inland in Russia it could get as cold as -50, -60 and even -70 °C.

So Allan had been lucky, and now he was pushed into a drafty freight car with about thirty other fortunate dissidents. This particular load had also been allocated no fewer than three blankets per prisoner after the physicist Yury Borisovich Popov had bribed the guards and their immediate boss with a whole wad of roubles. The boss of the guards thought it was weird that such a prominent citizen would care about a simpletransport to the Gulag camps, and he even considered reporting this to his superiors, but then he realised that he had actually accepted that money so perhaps it was best not to make a fuss.

It was no easy matter for Allan to find somebody to talk to in the freight wagon, since nearly everybody spoke only Russian. But one man, about fifty-five years old, could speak Italian and since Allan of course spoke fluent Spanish, the two of them could understand each other fairly well. Sufficiently well for Allan to understand that the man was deeply unhappy and would have preferred to kill himself, if in his own view he hadn’t been such a coward. Allan consoled him as best he could, saying that perhaps things would sort themselves out when the train reached Siberia, because there Allan thought that three blankets would be rather inadequate.

The Italian sniffled and pulled himself together. Then he thanked Allan for his support and shook hands. He wasn’t, incidentally, Italian but German. Herbert was his name. His family name was irrelevant.

Herbert Einstein had never had any luck in his life. On account of an administrative mishap, he had been condemned – just like Allan – to thirty years in the correction camps instead of the death he so sincerely longed

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher