![The Chemickal Marriage]()

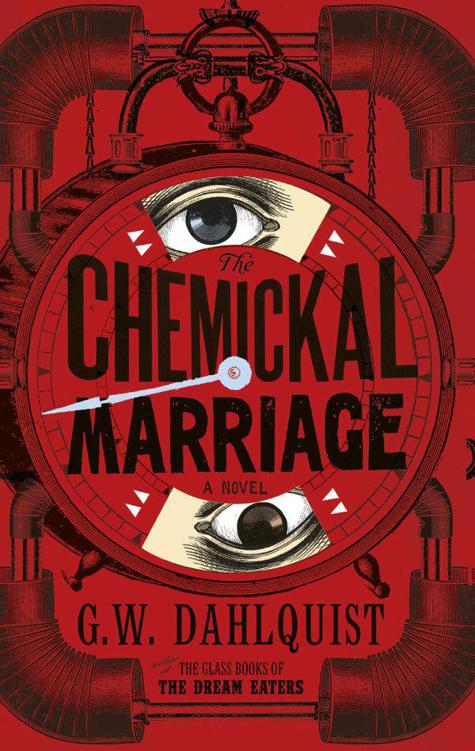

The Chemickal Marriage

‘lair’ certainly looked to be inhabited by an animal. Clothes, however fine, were strewn across the floor and furniture, unwashed plates and glasses cluttered the worktops, empty bottles had rolled to each corner of the room, a straw mattress had been folded double and shoved against the wall. Despite the Contessa’s detritus, it was clear the low stone chamber had been refitted for another purpose. Metal pipes fed into squat brass boxes bolted to the wall. The chamber reeked of indigo clay.

Svenson touched the pipes to gauge their heat, then put his palm against the wall. ‘Very cold … could that be the river?’

Chang slapped his hand against the wall. ‘Of course! I’m a fool – the Seventh Bridge! The turbines!’

‘What turbines?’ asked Miss Temple. ‘You say such things as if one mentions

turbines

over breakfast –’

Chang rode over her words. ‘The supports of the bridge contain turbines – it was an idea for flushing sewage –’

‘These pipes hold

sewage

?’

‘Not at all – the plan was never implemented. But we know Crabbé andBascombe plotted against their allies – so of

course

they required their own version of the Comte’s workshop. The bridge’s turbines, with the force of the river, would serve up enough power to satisfy even these greedy machines.’

‘And I assume the Contessa learnt their secret from her spy, Caroline Stearne.’ Miss Temple waved the reek from her face. ‘But why has she abandoned it?’

‘That is the question,’ agreed Svenson. ‘This night she has given up her refuge at the Palace, and now a quite remarkable laboratory …’

‘There is the matter of her death warrant,’ said Miss Temple.

‘It did not appear to trouble her especially.’

‘Also, if she lit the lamp and left the envelopes to get us here,’ said Chang, ‘where did she

go

?’

They did not see any other door. Svenson searched behind the mattress and under the piles of clothing, pausing at a wooden crate. The crate was lined with felt and piled with coils of copper wire. Next to it, in a tangle of black rubber hose, lay a mask, the sort they had all seen before in the operating theatre at Harschmort.

‘As we guessed, not only was our view of the painting leached from her own mind, it seems the Contessa did the leaching herself.’

‘How can she be sure the machine selects only the memory she desires?’ asked Chang. ‘Does she not risk its draining everything?’

‘Perhaps that is determined by the glass – a small card can contain only so much.’ Svenson moved on his knees to one of the brass boxes. It was fitted with a slot in which one might insert an entire glass book, but above this was another, much smaller aperture, just wide enough for a card. ‘I agree, however, that to do this alone is insanity. How can she rouse herself to turn off the machine? We have all seen the devastating effects –’

‘Did you see them in her?’ asked Miss Temple, just a little hopefully. ‘Thinning hair? Loosened teeth?’

‘Here.’ Chang held out a tiny pair of leather gloves, dangling them to show the size. ‘The Contessa took precautions after all.’

‘They would not fit a monkey,’ said Svenson.

‘Francesca Trapping,’ said Miss Temple.

‘The sorceress’s familiar.’ Chang hoisted himself onto a worktop to sit. ‘But I still don’t see why she’s left the place, nor why she’s bothered to lure us here …’

His words trailed away. Svenson followed Chang’s gaze to a china platter, blackened and split, piled with bits of odd-shaped glass, most of them so dark Svenson had taken them for coal. But now he saw what had caught Chang’s eye: in the centre of the platter lay a round ball of glass, the size and colour of a blood orange.

‘The painting,’ Svenson said. ‘The black Groom – in his left hand …’

Chang picked up the reddish sphere and held it to the guttering lantern above them.

‘It is cracked,’ he said, and pushed up his dark glasses.

‘Chang, wait –’

Doctor Svenson reached out a warning hand, but Chang had already shut one eye and put the other to the glass.

‘Do you see anything?’ asked Miss Temple.

Chang did not answer.

‘I wonder if it is infused with a memory,’ she whispered to Svenson. ‘And what could make it

red

?’

‘Iron ore, perhaps, though I couldn’t speculate why.’ Svenson sorted through the remaining pieces on the platter – several were obviously the remnants of other spheres that

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher