![The Merry Misogynist]()

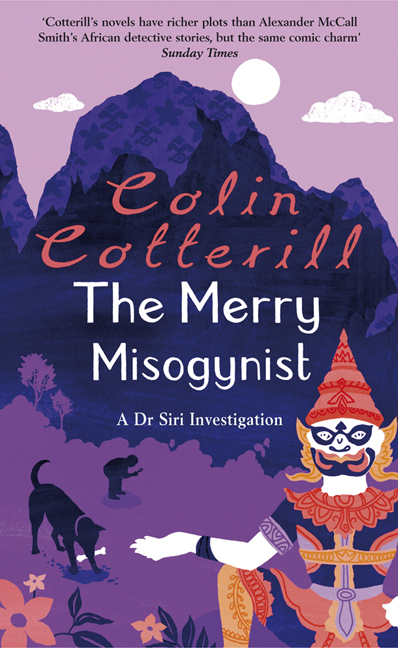

The Merry Misogynist

it might be the only way to find him.”

“Nit had a camera. The film was in it for a year or more. When he went into town to get it printed there wasn’t nothing but white.”

“I see. Is there any way we can get your wife back here to talk to? I think she should hear this.”

“You’re right.” Boonhee nodded at one of the silent youths and the boy set off across the fields at the speed of light. It had seemed hardly possible he could move so fast.

Boonhee’s wife was frozen into a fit by the news. Her husband had told her himself and shown her the photograph. She’d fainted. When she came around it astounded Siri just how many tears her dehydrated little body could produce. Still she couldn’t speak. Boonhee and Siri led her into the shanty and watched her lie on the thin mattress. Her body was curled in a knot of misery. Boonhee left her and walked with Siri to his bike.

“What else do you need?” he asked the doctor.

“Why was she covered? I mean when she worked in the fields.”

“Ngam? She was allergic to sunlight.”

“No she wasn’t.”

“Eh?” Boonhee stared at Siri.

“I’m a doctor.”

8

PALACE OF THE ONE HUNDRED AND ELEVEN EYES

A s he rode back towards Vientiane, Siri considered every astonishing fact he’d learned. He couldn’t bring himself to believe it. Ngam had been a pretty baby. The parents had been astounded they could ever have produced such a prize. They changed her name to Ngam, which meant beautiful, to reflect her looks. They knew she’d grow up to be as pretty as a picture. But Mongaew, her mother, understood that to be truly beautiful in Asia, a girl had to be white. In all the advertisements, in the magazines, in the travelling film shows before the takeover, all the classic beauties had skin as white as china.

When she herself was little, Mongaew had fantasized about her own life. If only she were white, she might grow up to be Miss Sangkhan at the provincial festival parade. She’d get to carry the four-faced head of Phanya Kabilaphon on the decorated chariot. It was all an unreachable dream. She was neither white nor particularly attractive. But now she had been blessed with a miracle: a girl child who might truly grow up to win the competition. If only – if only they could keep her skin from the sun. So Mongaew and Boonhee invented an illness for her, an allergy that prevented her from exposing her skin to sunlight. She’d seen a specialist in Thailand, she’d told the neighbours. The girl might die if she were to go outside in the daytime.

Ngam, of course, had believed her parents and done as she was told. She played at home with her brothers and covered herself from head to foot when it came to harvest time. A kindly teacher from the local school felt sorry for the girl and volunteered to come by in the evenings to give her vitamins and a modest education. When Ngam reached sixteen her mother used the money she’d put aside to record her daughter’s beauty at a professional photographer’s in Phonhong. She sent the resulting snaps to the organizers of the festival. One committee member came to the farm to see the girl, to verify that the beauty they’d seen in the photograph was not a trick of the light. She had been astounded that such a vision could rise up from these humble origins. She assured the parents that their daughter was guaranteed a spot in the next year’s competition, and – off the record – that Ngam was so lovely the organizer couldn’t see anyone beating her.

Mongaew was elated. She knew exactly what this meant. Every year, the winner of the Miss Sangkhan beauty pageant was handed a substantial sum of prize money. She would receive countless offers to advertise beans and cement and farm implements and soft drinks, all for a fee. But, most important, what wealthy man would not want to marry the most beautiful girl in the province? What a prize she would be. Money would flow onto Mongaew’s head like honey from heaven. All the planning, the inconvenience, would have been worth it. All their financial problems would be over. Mongaew had gambled with her girl’s life and won.

The following year, amid the political upheaval, and with the Royalists scurrying across the Mekhong, the Miss Sangkhan beauty pageant had been cancelled. “Next year,” she was told. “Next year everything will return to normal, and your daughter will take the Miss Sangkhan crown.” But in some stuffy socialist meeting, a decision was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher