![The Night Listener : A Novel]()

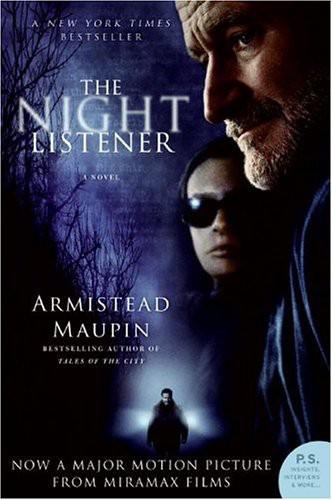

The Night Listener : A Novel

bedroom. Pap, scarcely out of his teens, had come home from a camping trip on Kiawah Island to find an old black retain-er—Dah, they called her—mopping gore off the wallpaper.

Another version placed the suicide in the garden after supper, when children were at play, and all of Meeting Street could hear the blast. Jim’s aunt Claire was out jarring lightning bugs at the time and remembers Dah’s terrible keening. Whichever rendition was true—if either—my father had been known to discuss the event only once in his life: with my mother, very briefly, on the night before their Eastertime wedding at St. Michael’s.

When I asked my mother why Grandpa Noone had killed himself, she told me he had lost money in the Depression. “And,” she added darkly, “there were too many women around.” (A mother-in-law and a maiden aunt had lived under the same roof with Dodie and Grandpa.) This, my mother suggested with breezy misogyny, was reason enough for any man to lose interest in living. But none of that mattered, she said. All that mattered was that Pap not have to think about this terrible thing again. So I joined her confederacy of silence, standing sentinel to a secret that wasn’t a secret at all.

I remember a night, not long after that, when my father and I were watching Playhouse 90 together. The show, I realized to my horror, was about a man coping with his father’s suicide. (Forty years later, I can still invoke the title: The Return of Ansel Gibbs .)

Too mortified to leave the room or change channels or even glance in my father’s direction, I held my breath for an hour and a half.

When I finally dared look, his face told me nothing. The man who always talked back to the bad guys on Gunsmoke sat as mute and unblinking as a corpse.

I began to wonder if suicide, like everything else in the family, was hereditary. Pap kept a captured Japanese pistol in his desk that I regarded with mounting dread. It was there, he said, in case he had to “stop some crazy nigger from breaking in,” but it was his craziness that worried me. Whenever he stormed off to his study after one of his tantrums I would listen for gunfire. I think he knew this, too. “Don’t worry about me,” he was fond of saying. “I won’t be around much longer.” This could have been a reference to his famously high cholesterol, or just the onset of middle age, but I took it to mean he would someday become his father’s son.

I guess he felt outnumbered. The four of us—my mother and brother and sister and I—had united in the face of his helpless fury.

And the thing we could never mention had dredged a gulf so wide that none of us could bridge it. Pap tried, in his own way. He surprised us with pet ducks one Christmas. He drove us to Quebec in the Country Squire, belting out the same two sea shanties all the way. But he was always the outsider, the Caliban we fled when things got scary. My mother was our harbor. She was all we needed to divine—and forgive—my father’s mysteries. He loved us, of course, but in a growly, jokey, ceremonial way, since real feelings had already been proven to hurt too much. And this got worse as time went on. I remember being held by him when I was six or so, but not much later. When he and my mother met me at the airport after my first semester at Sewanee, I tried to hug him, but his arm shot out instead for a blustery handshake, as if to say, Please, son, no closer, no closer .

After that, I stopped trying.

“You have reached the Noones. At the tone, you have sixty seconds to leave a message.”

Pap’s new machine threw me. It was weird to hear his antebellum voice in such a postmodern context. And weirder yet to think that

“the Noones” meant him and Darlie Giesen, a classmate of mine in high school, circa 1962. December had met and courted May several years after my mother died of breast cancer in 1979. Now they owned a condo on the Battery in Charleston, the very spot where the first shots of the Civil War were fired. The very spot, I might add with no small degree of irony, where the third Gabriel Noone first discovered the pleasures of sucking cock.

“Hey,” I told the machine, “it’s Gabriel. Anna says you’re heading west. That’s great. It’s a real busy time for me, but maybe we can have dinner or something. I’m here most of the time, writing away, so…call when you can.” When I put the receiver down, Anna was smirking at me.

“Not a word out of you,” I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher