![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

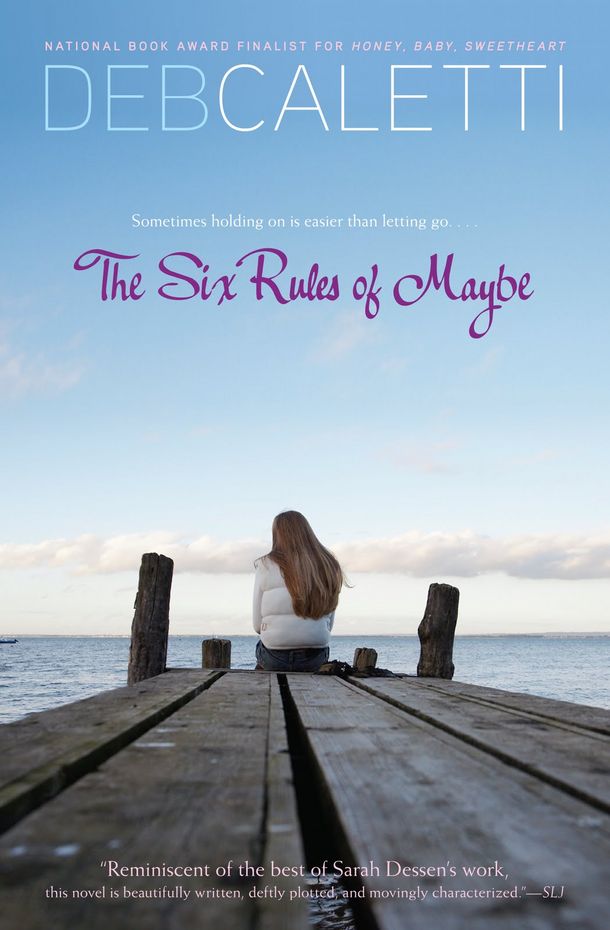

The Six Rules of Maybe

with its dry yellow grass and padded white bases set on dusty ground. I wondered if Hayden had played baseball in high school. I pictured him with a mitt on his hand, a dog running around his legs. I wondered who he was as a boy. If he rode his bike or collected bugs or grew a sunflower in a Styrofoam cup in the first grade. A person can seem like a whole country you’ve never been to.

The deep desire to see someone again, to know more: Was it fate shifting its pieces, or just what my psychology books would say—that instant connection is your past at work, the reminder of something, or the hope of something else? My mind kept bumping into him. God, I was acting like someone with a crush . I’d better not have a crush on him. First, he was Juliet’s husband, and that was not something you conveniently forgot. Besides that, I hated the word crush , a pink candy word, a frosting word, something for giggly girls who wrote their name with his surrounded by a heart. I wasn’t the kind of person who had crushes. I didn’t believe in stupid insta-connections with people you didn’t even know. It needed to matter, it needed to come to something, be real , or it wasn’t worthall the wasted feelings. Everyone else, even Juliet, fell in love with Mr. Gregory Hawthorne (who let us call him Gregory), our middle school algebra teacher. But I’d only noticed how he paused by his reflection in the classroom window, and how his breath smelled of coffee when he stood too close.

And what was curiosity or gladness or intrigue, anyway? Just regular human being feelings. People could have all kinds of feelings, and that didn’t necessarily mean anything. It didn’t mean that anything would happen .

I hurried through lunch. There was someone I had to talk to. Goth Girl had reached out to me, and hers was a problem I could do something about. She had drawn a red Volkswagen, and there were only two red Volkswagens in our school lot. Henderson Law, super-jock, perpetual Homecoming King—I knew it couldn’t be him. But the other Volkswagen belonged to Kevin Frink. Bomb Boy. Kevin Frink, with his heavy jacket and averted eyes and pocket full of matches. It made perfect sense, the kind of perfect sense that’s actually the strangest and most bizarre perfect sense possible.

I knew Kevin usually hung out around the football field bleachers at lunch. The last time I saw him there he had a couple of firecrackers and a small package of matches from some seaside motel in Oregon. I walked through the stadium gate and down the bleachers, but didn’t see him until I looked out onto the field itself. He sat on the AstroTurf with his back against a goalpost. I wondered if I should ask him about Clive Weaver, but I could imagine Kevin’s voice. Just because my mother drives a hearse doesn’t mean I know when everyone dies. When I got down there, he looked up from a roughed-up copy of The Anarchist Cookbook .

“You said you weren’t going to want something for not rattingon me and now you want something,” he said.

“How’d you know?” I asked.

“People always end up wanting something,” he said. He shoved his hair up out of his eyes with his palm. He had dark long hair that fell over a big forehead. Kevin Frink was a big guy. He had been known as the Kid with the Big Head since elementary school. This had changed to Bomb Boy when he lit his first cherry bomb in the gym during the PE basketball unit in the seventh grade.

“Can I sit down?”

“Whatever. I don’t own the place.” Kevin Frink breathed heavily when he spoke. It was the exertion of weighty things—his bulky body, his burdened life.

“Do you know Fiona Saint George?”

“Vampire. Who doesn’t?”

This didn’t seem to be a good start. “She’s a great artist,” I said.

“What does that have to do with anything?” Kevin Frink grabbed at a clump of AstroTurf as if it were grass and pretended to throw it a few inches away.

“I think she really likes you.”

Kevin snorted.

“No really. Maybe a lot. Maybe enough to go to the prom with you.”

“You’re out of your mind.”

“No. I know it’s true.”

“Is this some kind of joke?” I knew Kevin Frink was thinking about the time those kids put a dead deer in the hearse his mother drove for Simmons and Sons Funeral Home. Or maybe about that year that Steven Gardener and his friends spent every lunch trying to step on the back heels of his shoes. “Not me,” he said.

“I wouldn’t lie

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher