![The Twisted Root]()

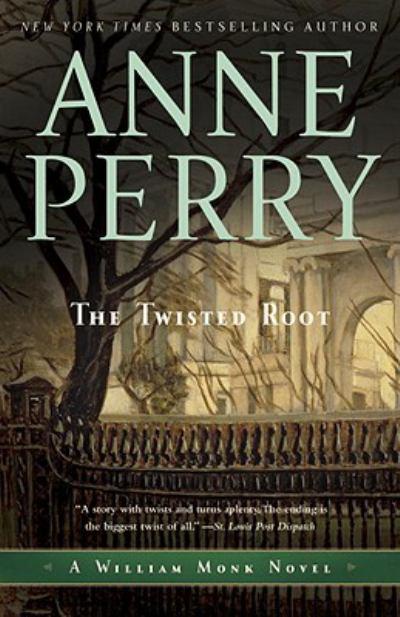

The Twisted Root

know. I can’t think of any reason why they would hurt either Mrs. Stourbridge or, still less, Treadwell. But he was a blackmailer. If he would blackmail Cleo, then maybe he would blackmail others as well. William says he seemed to spend more money than he could have had from Cleo, so there will have been other victims."

"Lucius?"

"Perhaps," she said quietly. "That would explain why Miriam is prepared to defend him, even at the price of being condemned for it herself."

It was possible. It would explain Miriam’s refusal to tell the truth. But he still found it hard to believe.

"I cannot think of anything we could argue which would convince a jury of that, especially in the face of Miriam’s denial," he said, watching Hester. "And she would not let me try. I have promised not to act against her wishes."

A smile touched the corners of Hester’s lips and then vanished. "I would have assumed as much. I would like you to be able to defend Miriam, but I am more concerned with Cleo Anderson. I hope she did not kill Treadwell, but she cannot have killed Mrs. Stourbridge. I am absolutely sure she would not have conspired for Miriam to marry Lucius, or anyone else, for money. That part of it is simply impossible."

"Even to put to a good cause?" he asked gently.

"To put to any cause at all. It would be revolting to her. She loves Miriam. What kind of a woman would have her daughter marry for money? That’s prostitution!"

"Hester, my dear! It is the commonest practice in civilization. Or out of it, for that matter. Parents have sold their daughters in marriage, and considered it as doing all parties a service, since time immemorial—longer. Since prehistory."

"Isn’t that the same?" she said tartly.

"Actually, no. I believe ’time immemorial’ is in the middle of the twelfth century. It hardly matters."

"No, it doesn’t. Cleo would not sell her daughter, and she certainly would not conspire to murder someone who got in the way. If you knew her as I do, you wouldn’t even have thought of it."

He did not believe it either, but it was what a jury would believe that mattered. He pointed that out to her.

"I know," she said miserably, staring at the floor. "But we’ve got to do something to help. I refuse to hide behind an intricacy of the law as if it excused one from fighting."

He found himself smiling, but there was no laughter in it, no light at all, except irony. "Murder is not an intricacy of the law, my dear."

She looked at him with utter frankness, all the old friendship warm in her eyes, and suddenly he was short of breath. The final bit of denial of his emotions slipped away. He forced his mind back to the law and Cleo Anderson.

"How much medicine is missing, and exactly what?"

She looked apologetic. "We don’t know, but it’s a lot—a few grains a day, I should think. I can’t give you precise measurements and I wouldn’t if I could. You would rather not know."

"Perhaps you are right," he admitted. "I won’t ask again. When the matter comes to court, who is likely to testify on the thefts?"

"Only Fermin Thorpe, willingly—or at least not willingly but for the prosecution," she amended. "He’s going to hate having to say that anything went missing from his hospital. He won’t know whether to make light of it, and risk being thought trying to cover it up, or to condemn it and be seen on the side of the law, all quivering with outrage at the iniquity of nurses. Either way, he’ll be furious at being caught up in it at all."

"Is he not likely to defend one of his staff?"

The look in her face was eloquent dismissal of any such prospect.

"I see," he concluded. "And the apothecary?"

"Phillips? He’ll cover all he can—even to risking his own safety, but there’s only so much he can do."

"I see. I will speak with a few of the other nurses, if I may, and perhaps Mr. Phillips. Then I shall go and see Sergeant Robb."

It was early evening by the time Rathbone had made as thorough an examination of the hospital routine as he wished to, and had come to the regrettable conclusion that it required considerable forethought and some skill and nerve to steal medicines on a regular basis. The apothecary was very careful, in spite of his unkempt appearance and erratic sense of the absurd. Better opportunities occurred when a junior doctor was hurried, confused by a case he did not understand, or simply a little careless. Rathbone formed the opinion that in all probability Phillips was perfectly

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher