![Up Till Now. The Autobiography]()

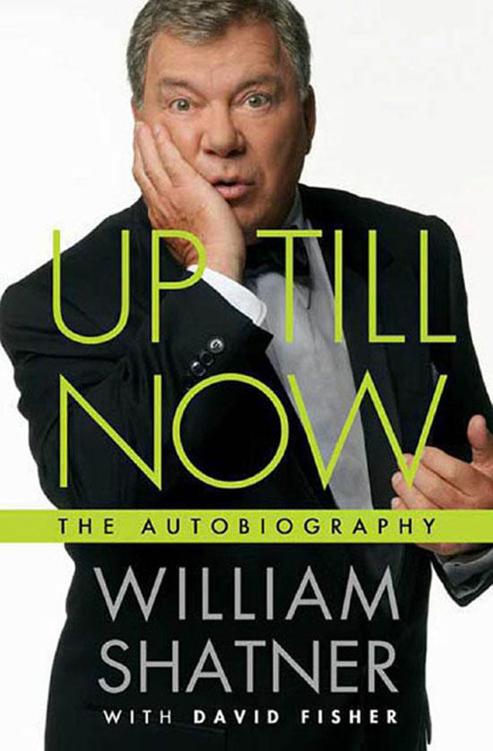

Up Till Now. The Autobiography

arm. It had been an amazing day: after flying in a paraglider I’d been running around in the heat all morning, wearing very heavy protective clothing. I was covered with sweat. I sat down in the shade and leaned against a tree. My breathing became loud and labored. “I think I’m having a heart attack,” I said with astonishment.

The action stopped as the news spread quickly: Shatner’s having a heart attack. Instantly, people came running from all over. Somewhere behind me I could hear someone calling for an ambulance. Finally the commander of the enemy came over to help me. It was obvious he was very concerned. He leaned over, and asked, “How you feeling, Bill?”

“Fine,” I said, smashing him in his chest with the two paintballs I was hiding in my hand. “Gotcha!” Hey, it’s not my fault they forgot I was an actor. Captain Kirk lives!

The truth is that for some inexplicable reason physical fear has never bothered me as much as emotional fear. I have never worried very much about getting hurt, while I have spent many a sleepless night being terrified of failure. Terrified I would never get another acting job, terrified I wouldn’t be able to fulfill my responsibilities. During these times my daughters would refer to me as Black Bill, as in: “Dad’s being Black Bill,” meaning I was in a dark mood. I withdrew, I didn’t want to talk to anyone. After Star Trek was canceled, for example, I went through one of the most difficult periods of my life. I wasn’t particularly worried about myself; I’m a resilient person, I knew I would be fine, but I spent many sleepless nights worrying about how I was going to support my ex-wife and my three daughters.

Star Trek was mostly perceived to have been an interesting and expensive failure. It had lasted only three seasons; we had just barely made enough shows to allow it to be sold in syndication. But as far as I was concerned, I’d put away my phaser forever. My greatest regret was that it did not lead to any other substantial offers, so I really had to start all over again. Leonard accepted a starring role on the already successful series Mission: Impossible , a role he played for two seasons and very quickly grew to despise.

Once more, I was broke. I needed to earn some money very quickly, so I decided to perform in a play on the summer circuit. I went on tour in a very flimsy British sex comedy entitled There’s a Girl in My Soup . When it had opened on Broadway Edwin Newman described it as “the sort of English play that prevents American theater from having a permanent inferiority complex.” I played an aging bachelor pursuing a beautiful young woman whose greatest talent was her microskirt. It was a perfect play for the suburbs. We played a different theater each week. To save money, I’d bought myself a ram-shackle pickup truck, put a camper-shell in the rear bed, and drove it cross-country with my dog. Each week I’d park the truck way in the back of the theater parking lot and live in it. Just an actor and his dog, living in the back of a truck. It was depressing beyond any imagination. I was absolutely broke, terribly lonely, terrified of failure, and starring in a comedy.

During the day I would do whatever publicity the theater management asked me to do. After each performance I would wait outside to greet the audience and thank them for coming. And then I would go home to my truck. This was the difference in life between comedy and tragedy: when I had been starting my career, if I’d been this carefree bachelor living in a truck, inviting women over to see my carburetor, it would have been a very funny situation. Instead, I’d been a working actor for decades, I’d starred in three failed TV series, and I was a divorced father of three children living in the back of a truck. That was a tragedy.

A summer later I co-starred with Sylvia Sidney and Margaret Hamilton in a Kenley Players production of Arsenic and Old Lace . The producer, John Kenley, had been very successful on this straw-hat circuit by bringing television stars to his theaters in Ohio. As those who worked for him know, John Kenley was a...an... interesting man. Or woman. Or both. He would spent summers in the Midwest as a man and the winters in Florida as a woman named Joan Kenley. When Merv Griffin wrote that John Kenley was “a registered hermaphrodite,” Kenley responded, “I’m not even a registered voter.” Although in his autobiography Kenley admits,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher