![What became of us]()

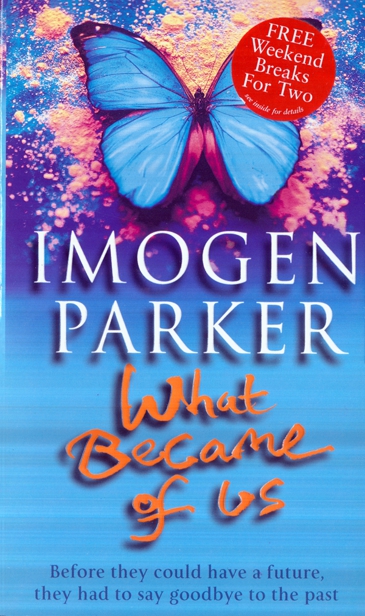

What became of us

packet of cheese and onion crisps then picked up her magazine again. The sound of crunching was like someone stamping on brown paper bags, and a slight synthetic onion smell wafted over, making Ursula glad about her decision to avoid food.

I betrayed my husband and my best friend screamed the headline of the magazine.

The woman opposite was obviously an avid reader, because most of the month’s glossies were fanned out on the table between them.

How does he really see your body? asked the cover of the unopened Cosmopolitan. The you-can-do-it experiment that proves he desires you more than you think...

‘Do you mind if I have a look?’ Ursula asked.

The woman lowered her copy of Panache.

‘Go ahead.’

The feature asked boyfriends to draw a picture of their girlfriend’s body. All the women were young enough to be her daughter, Ursula thought. It was a long time since she had read Cosmopolitan, and it seemed to be aimed at younger women now. Or was that just like thinking that policemen were younger? The women, all of whom were stick thin, had drawn themselves unflatteringly, and then, rather sweetly, their boyfriends had drawn them with the body image that they hoped would satisfy their girlfriends’ anxieties.

Ursula remembered the painting that her oldest son Chris had brought home one winter’s day during his second term at nursery school. It was more considered than his usual primitive abstract and it was the first time she had seen him attempt to draw people. She had been delighted with the two figures.

‘That Daddy!’ Chris had told her proudly pointing at a face with two spokes sticking out of it horizontally, which she guessed were arms, and two vertically which were legs.

‘And that’s the snowman!’ she said, because they had made one together the previous weekend.

‘No, that you, Mummy,’ Chris had told her, impatient with her inability to see something so obvious.

How would Barry draw her body? Sometimes Ursula wondered whether he had even noticed that she had lost four stone in the last year. But he had loved her through all her metamorphoses. He had loved her when she was technically obese, he had loved her in pregnancy when her breasts were so distended under the stretched white skin they looked like blue cheese. He had even loved her when her hair had come out disastrously tangerine instead of strawberry blond. She knew that had looked horrible because no-one, not even her secretary, had remarked on the glaringly obvious change, and when she had finally screamed at Barry, ‘Well, what do you think?’ he had replied, ‘I wasn’t going to say anything because I thought it might be a mistake.’

Barry wasn’t good at compliments like he wasn’t good at gifts. But just as he never forgot to hand over generous quantities of vouchers on anniversaries, birthdays and at Christmas, so he had always been there with generous supplies of love. Even when her eyes were a nondescript brownish colour.

It was very easy to take someone nice for granted.

It was very easy to despise someone for being stupid enough to love a fat, mousy woman.

Ursula put the magazine down and stared out of the window, seeing nothing. Her brain felt like a soft mush of guilt which was being prodded occasionally by an electric knitting needle to provoke images of her wrongdoing.

She tried to focus on something different. Closing her eyes, she attempted to remember the contents of the briefs she was preparing at work. There was a kid with no previous record who had been caught with a small amount of cocaine and a large amount of cash, who had been charged with intent to supply as well as possession. The case was going to turn on where the money came from and she knew that the boy was too stupid to make up anything plausible. It seemed so unfair that he would probably go down because he had little imagination and lived in a council flat and therefore needed to explain why he had five hundred pounds. It occurred to her that a student at Oxford in a similar predicament would probably not even face questioning about the money. Oxford always twisted reality, she thought.

Her other client about to face a jury was a childminder accused of shaking a child. Her only defence would be to try to shift the blame to the parents. Ursula was not looking forward to that. The child was alive, but brain-damaged, which made it more likely that her client would get off, because it was going to be quite difficult for the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher