![What became of us]()

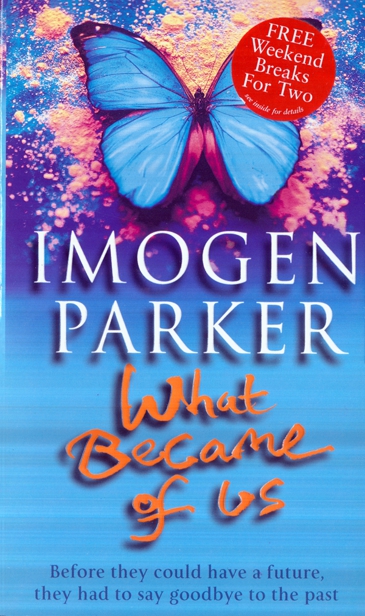

What became of us

she had probably got the better deal.

‘OK. Shall we go back?’

Annie took a long drag, then stubbed the cigarette out on the road.

‘I think I will just pop to see Penny’s grave,’ she said.

‘It’s over there, you can either go round the road to the church entrance, or climb over this wall and go through the meadow. The grave’s round the other side.’

‘Do tell Geraldine where I am. I couldn’t bear her to think I’d just nipped out for a fag.’

‘Of course not,’ Manon smiled again.

‘And save me a burnt offering.’

Chapter 42

Should she tell Barry?

Ursula took out her compact, looked at herself in the mirror, then looked away and back again quickly, trying to catch herself out. Did she look different? Every time she looked, her eyes seemed to be a more virulent green and her hair a brassier shade of chestnut. She was a fake. Liam had fancied a woman who was not her at all.

Would Barry notice?

She stood up and walked along the fast-moving train, stopping and reaching to grab the knobs on every other seat to steady herself. Why did they not put knobs on every seat, instead of making you take great leaps, she wondered, as the train clattered over points and her hips crashed against another passenger’s copy of the News of the World.

In the toilet, she rocked from side to side, her hands poised for a moment when she would be able to whip out a contact lens without stabbing her eye with a fingernail. When she had them both removed, she tipped her head back and dripped in some saline solution. Most of it ran down her cheeks, some dropped directly to the unpleasantly puddled floor. She did not think that the other spillages there had been caused by contact lens solution. She felt so jumpy and anxious, she couldn’t be sure if she needed to wee or not, and just as she had decided that she might as well try, the train slowed, and she knew that you weren’t meant to go while the train was in a station. It was one of the things you were told as a child, but never quite understood. It had given her an unhealthy fear of going to the toilet on trains, because she had imagined guards opening the door to check what was happening every time the train stopped. She sat holding herself in until the train started again, and then the pathetic dribble of urine that emerged was hardly worth waiting for. Dehydration, she thought. There was no toilet paper. She was very aware of the fact that she had not washed herself. Liam’s request for a shower had infuriated her in her panic to leave, but now she thought it would have been sensible to shower herself, even if it had meant missing the first train.

Did she smell?

Ursula sniffed her armpits.

Had the experience of adultery changed her in indefinable ways she could not detect? As soon as she reached home she would run upstairs, lock herself in the bathroom and scrub every trace of Liam away.

‘No time to shower,’ she rehearsed saying into the small mirror above the dirty basin.

But she wouldn’t be able to do that, she realized, on the walk back to her seat, because George would need a cuddle, and an application of calamine lotion. She tried to envisage the bathroom cabinet, picturing a half-full glass bottle of pink stuff behind the cotton buds and the packet of disposable razors that fell out whenever she opened that side of the cupboard.

She wished she had remembered to tell Barry to put George in a bath with bicarbonate of soda in it. It was helpful for the itching. There was bound to be some in the kitchen, but perhaps it would be worth stopping off for a fresh supply at a chemist’s on the way home in the taxi. Except it was Sunday, she reminded herself. Better to get home and take over, then Barry go and find a twenty-four-hour chemist. Hopefully then she could settle George in front of a video, Chris and Luke could play on the computer and she would have a chance to scrub the odour of betrayal from her. And wash out her knickers.

The rattling progress of the drinks trolley sounded as loud as a clanking dustcart. She bought a fizzy mineral water. Her third that day and yet still she wasn’t weeing. Her body had become a sponge.

‘Anything to eat?’ asked the lady in charge of the trolley.

Ursula was simultaneously nauseous and starving hungry. She perused the labels on the sandwiches. There was only chicken tikka. She didn’t think she could arrive home unwashed and tasting of curry.

The woman opposite bought a coffee and a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher