![What became of us]()

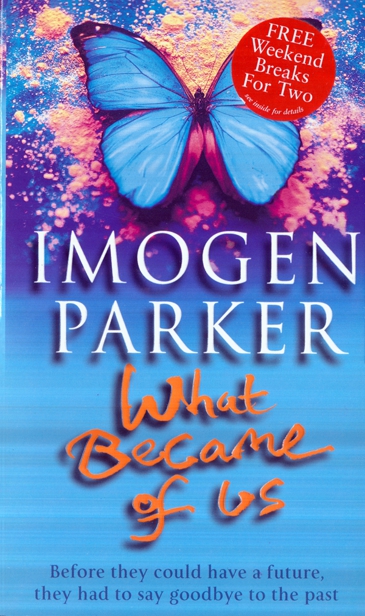

What became of us

either,’ Lily added. ‘I want to be with Mummy.’

He didn’t know in what sense his younger daughter could remember Penny. She had only been two when she died. He thought that what she missed was the total security of Penny’s mothering that nothing he could offer would ever approach. He wondered whether she could see Penny’s living face when she closed her eyes, or whether her recollection was a static image from a photograph.

‘If we’re going punting, you’d better get shorts and T-shirts on,’ he told them.

Geraldine had dressed them in pretty pastel dresses with matching cotton hats. He didn’t like them being dressed in the same clothes, but he didn’t think it was the time to say it. Their looks and characters were so different. Saskia like a tiny diffident model of her mother, and Lily so much darker and braver with brown eyes and curly hair that had to be cut short to keep it tame.

‘But they look so pretty,’ Geraldine said.

‘They’re not starring in a Merchant Ivory film, Geraldine, they’re going on the river, which is muddy and full of weed.’

‘You’re quite right,’ she told him, tacitly admitting her mistake. ‘Come on, girls!’

‘Punting, punting!’ Lily galloped after her.

It was a beautiful summer day. The verges were lush with grasses and clouds of cow parsley. The air was sweet with pollen. It was the sort of day when whatever your anxieties, you couldn’t help feel glad to be alive.

It was right for children to grow up in the country, Roy thought, watching their faces in the rearview mirror as the car wound up out of the village towards the main road. They were pink from a morning playing outside and Saskia’s nose had a spattering of freckles.

The house he and Ursula had lived in as children had no garden, only a yard outside. Their mother, who was a nursery school teacher, had read to them of children who spent holidays with distant aunts who lived on farms. He realized now that the books had been anachronistic even then, with their nostalgic descriptions of hand-churning butter and running barefoot to watch steam trains. They had made him yearn for a life that had already disappeared.

Even with crop-spraying and organophosphates, country life must still be healthier for children, mustn’t it? There was a stream in the village with fish in it. His children would grow up with the sound of the wind around the rafters as they fell asleep breathing clean air, far away from the drone of traffic and the invisible threat of exhaust.

‘Where did Manon say she’d meet you?’ Roy asked as they approached North Oxford.

‘She didn’t say,’ Saskia replied.

‘Well, where do you usually go, Cherwell boathouse or Magdalen Bridge?’

He looked in the rearview mirror and saw that Saskia was mystified by his question.

‘Normally, she meets us at Nancy’s...’

He didn’t want to get into the debate about home again.

‘Well, I think we’ll just pop into Mummy’s college and see how Leonora’s getting on, and then we’ll see if Manon’s at Cherwell boathouse, shall we?’

‘OK, Daddy,’ Saskia said.

‘I don’t like Leenora,’ Lily announced.

‘Why? She’s always very nice to you,’ Roy said.

‘She sings,’ Lily said.

Roy wondered at what age his younger daughter’s honesty would be suppressed by a developing sensitivity to other people’s feelings. At the moment she was hoovering up vocabulary and testing it out with no idea at all of the effect she was having. On being introduced to the Master of his college she had announced in a voice like a bell, ‘You are quite bald, aren’t you?’

‘But you like singing,’ Roy told her.

‘Not all the time,’ Lily replied, sulkily.

His three-year-old had pinpointed exactly what it was about Leonora’s company that made him feel agitated. She was one of those people who could not let silence reign for more than a few seconds. Even if there was a natural pause in the conversation, she felt obliged to fill it with a hum or a short blast of a scale, like a professional soprano warming up. He knew she had quite a good voice and sang in several choirs. Leonora was an operatic name. He wondered suddenly whether her parents had had ambitions for her when they named her, and for a moment he felt himself feeling a little sorry for her.

‘I want you to be on your best behaviour because Leonora has put such a lot of work into this evening,’ he said.

‘Why?’ asked Lily.

‘For

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher