![What became of us]()

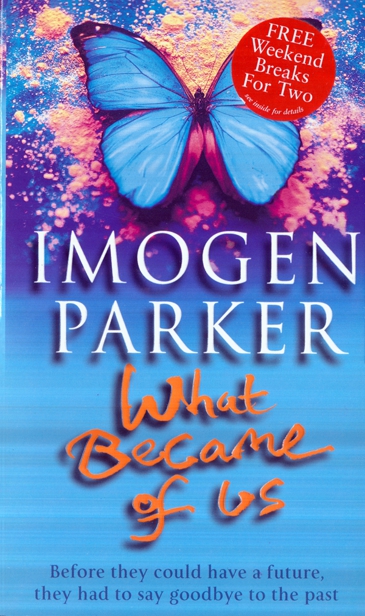

What became of us

jam that you had to pay for.

Annie took off her dress and hung it on a hanger in the wardrobe. It was one of those detachable hangers that wouldn’t hang anywhere except in its casing on the rail and it annoyed her. Did hotels really think that people were going to steal their poxy coat hangers. Well, how much did a coat hanger cost, anyway, for God’s sake? If you were charging over a hundred pounds per night, surely a stolen coat hanger or two would not eat too voraciously into your profit? She threw open a window. The rain had stopped and the air was cool on her damp skin, like witch hazel.

She looked out of the window at the world going by below. When she was a student the idea of having enough money to check into a hotel like this would have been unimaginable. It was a mark of her achievement, she thought, to have become so blase that these small pleasures no longer held any excitement for her. She wondered if this had been Liz Taylor’s room and whether she had felt the same way. Then she spied the room service menu and ordered a cafetiere of freshly ground Colombian coffee and a cream tea. She would run a bath and while she soaked she would think about what she would say about Penny at the dinner. She caught sight of herself in the mirror above the sink and rang down to cancel the tea.

Annie stepped into the bath and sank down through the cool caress of bubbles into the deep, fragrant warm water. The hangover and lunchtime champagne had depressed her spirits, she reasoned, but really there was nothing to be depressed about. She was certainly the most successful and famous woman of her year in college and she was damned if she was going to let anyone ruin her triumphant return. And yet however logical she tried to be, Oxford still made her feel inferior, as it always had.

Since leaving, she had tried therapy (individual, group and aroma), reflexology, detox diets, vitamin supplements, pop psychology, serious psychology, crystals, and even a couple of quasi-cults, but still deep down, or sometimes quite near the surface, she was a trembling mass of insecurity. Particularly the mass bit, Annie thought, sinking further into the water to submerge the folds of her tummy. Maybe she had a chemical imbalance, she thought. Maybe her serotonin-inhibitor levels were too high or low or whatever it was, and she would be better off with Prozac, but having read Brave New World at the age of fourteen, she was suspicious of it. Maybe she should stop eating sugar. Or maybe the simple explanation was that she really was inferior.

‘Girls like you do not go to Oxford,’ her headmistress, Miss Greer, had told her on the occasion she had been caught in the cloakroom selling lipstick samples she had nicked from her mother’s demonstration kit.

Annie had never been sure whether it was the lipstick itself (shade: Purple Grape) that had offended the headmistress, or the fact that she was asking money for something that had not for Resale stamped all over the box, or whether it was simply that she was the daughter of an Avon lady, when most of her peers had nice families with fathers who were surveyors or solicitors.

Girls like her did win places at Oxford, it turned out, especially when they had something to prove, hut Miss Greer had been right in another way because when they got there they were even more out of place than they had been as scholarship girls m posh schools.

The first evening at college made Annie cringe now as it had then. There had been a sherry party to welcome the freshers. Annie had no idea how to bold a glass of sherry and a cigarette and shake bands with her tutors all at the same time. Several times her shoulderbag clonked down her arm to her elbow, jolting the half-schooner of Tio Pepe, and splashing its contents onto her new clompy-heeled suede shoes.

If you didn’t have class, you were no-one at Oxford. The strange thing was that until she changed schools after O levels, she and her mum had always thought that being an Avon lady was class. Her mother always made her talk nicely and the television in their home was rationed to costume dramas and University Challenge, which was where Annie had heard about Oxford in the first place.

‘You can do anything you want to,’ Marjorie had always told her. ‘Look at me!’

Annie’s childhood had been spent in and out of hostels and bedsits while Marjorie struggled to find a job that would provide the income and flexibility to look after them both.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher