![When You Were Here]()

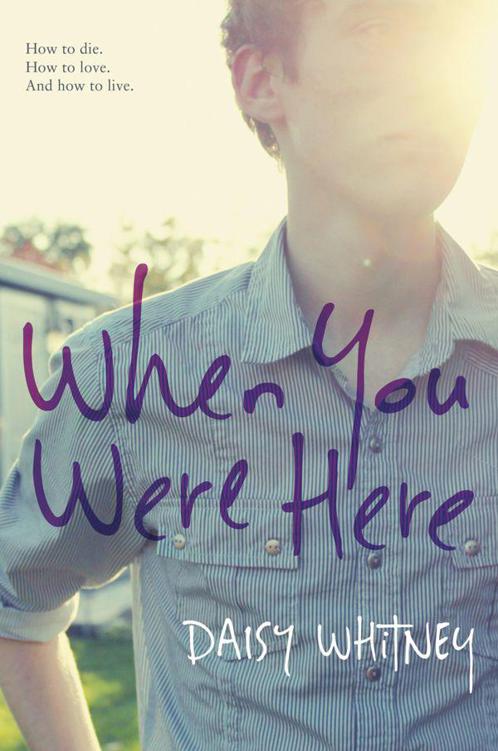

When You Were Here

walk home, since it’s only a couple miles away, chucking my cap and robe into a trash can on a street corner, then I change into gym shorts when I get home and head to the garage, my dog following close behind as I park myself on the gym bench out here. Yeah, this is my life. Working out on graduation. What could be better than this?

But I don’t want to go to a party, and I don’t want to have some fancy meal at some fancy restaurant with people who are pissed at me, or people who feel sorry for me, or people who feel both, not to mention my own disgust at what the guy on the stage wearing my cap and gown just did.

Besides, I have to figure out what to do with all our stuff . Kate may be the executor of my mom’s will, but Laini and I are the ones she’s executing for, and there’s so much stuff to figure out, money to be moved around, accounts to be administered, possessions to be dispersed.

Like wigs. Like, what do I do with all those wigs?

I manage a dry laugh, because it was so much easier— easy being an incredibly relative term—when my dad died. My mom handled it all. She managed all the phone callsand decisions while Holland made brownies and showed me stupid cat videos on the Web to try to make me laugh again. Because that’s what my dad and I had always done together— fun . We did fun incredibly well. We’d spend entire Saturdays in the pool, inventing games and racing each other. We’d go out for doughnuts or ice cream and talk about random things. We’d read every book in the Get Fuzzy collection together. When he was gone, that fun rudder was out of whack, and Holland was determined to fill the role of humor producer in my life. She did it ably, all while my mom kept us going as a family.

But now my parental insurance policy has run all the way out, and so it’s up to my sister and me to figure out things like wigs and college funds and the apartment in Tokyo.

I start chest presses and let my thoughts turn to Tokyo, where I was born, since my parents both worked for Japanese companies at the time. We moved back to California when I was three, but we kept returning to Tokyo for vacations. Now we have a place there, an apartment in the Shibuya district, the center of young Tokyo, with neon and lights and billboards the size of Mars, with shops and stores open at all hours and über-trendy girls who click-clack down the sidewalks in gold high heels and playing-card earrings, and dudes who wear plaid pants and black lace-up boots.

Back when we were a foursome, we’d spend summer breaks and winter breaks in Tokyo. My dad, my mom, Laini,and me. Eating noodles and fish, buying manga I couldn’t read, asking whoever walked past to take our picture.

I haven’t been to Tokyo in a year because I was too busy as a senior—too many tests, assignments, college apps, and so on. But my mom traveled there to see Dr. Takahashi, who runs a clinic for cancer patients that’s part Eastern medicine, part Western medicine. For her first trip to see him, I drove her to the airport and walked her to security. She was practically bouncing the whole way. “If there is a miracle cure, this is it. He is it,” she said. She believed in him, and so I did too, especially when she felt better than she had in years. It was working, his mix of traditional medicine and alternative treatment. Takahashi was my mom’s last great hope, so she saw him at least once a month in the last year. Filled with hope each time. I was filled with hope each time. For a while there, all that hoping brought its rewards.

Now all I have is an apartment in Tokyo to show for so much wishing, so much wanting.

Because Laini told Kate last week— e-mailed Kate, I should say—that it was entirely up to me to decide what to do with the apartment in Shibuya.

Do I keep it or sell it? Rent it? Or say to hell with California and set up a new home far, far away from here?

I risk a grin at the thought. Because there’s a part of me that likes that idea. Get out of town and never look back.

I switch to the dumbbells, working on triceps, then biceps, thinking of the empty apartment, picturing dustgathering on the wooden slats of the futon in the room I slept in. I’ve never had a bad time in Tokyo. Never had a bad time at all.

Maybe it’s time for me to go back.

I put the weights away and turn to Sandy Koufax. “Do you want to go for a walk?”

She wags her tail. She likes the word walk .

I go back into the house, ignoring the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher