![Wild Awake]()

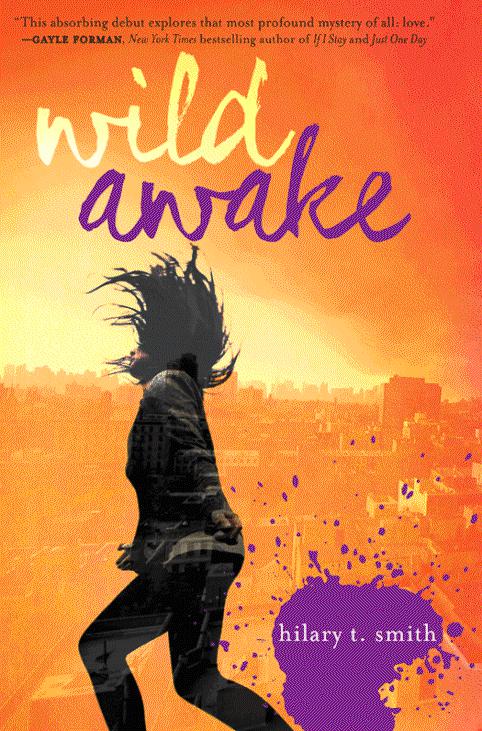

Wild Awake

out strange and strangled, like words in a foreign language I’m only beginning to learn.

Then they’re hugging me in their sunscreeny arms and breathing in my hair with their mouthwashy breath, and I feel like a firewalker who’s just crossed hot coals to collapse, on the other side, into cool grass.

“There was a phone call,” I mumble into the sleeve of my dad’s shirt.

We start from there.

chapter forty-three

That night, I do my incense ritual standing over my bed, and I’m just about to swallow the melatonin Mom left on my dresser when I realize I haven’t checked my phone all day. I fish it out of my purse and see three missed calls from Skunk, and two texts from this afternoon: JUST BIKED PAST IMPERIAL. ALL BOARDED UP. ??? And: TALKED 2 CONSTRUCTION GUY. DEMOLITION 2MORROW!!!

I spit the melatonin into my hand and press call back. Skunk answers on the twenty-millionth ring, his voice thick and groggy from his medication.

“Huhllo . . .”

“They’re tearing it down tomorrow ?” I whisper.

“Mmmmmmm.”

I don’t think he’s really awake, or even physiologically capable of being awake. The pills he takes are basically elephant tranquilizers.

It occurs to me in a flash that starting tomorrow, the Hip Young Counselor might try to put me on elephant tranquilizers too.

Skunk makes a sleepy, confused moan. I whisper lovingly, “It’s okay, Bicycle Boy, go back to sleep.”

I press the end button and sit on my bed, my body straining between rival impulses like a chew toy being pulled in six different directions at once. I know I should go to sleep. I should take the melatonin and get into bed. But when I think about everything that’s happened this summer, I can’t let it end like this, with a pill and eight hours of chemical oblivion. It would be like skipping Sukey’s funeral all over again. It would be like I never went out to find her at all.

The house is quiet. The only sound I hear is the barking of a distant dog through the open window, blocks and blocks away.

Just one more night , I say to myself.

I get up and pad down the hall, pausing outside my parents’ door to make sure they’re asleep. They kept yawning during dinner and making comments about being on “Canary Island time,” and I’m pretty sure they’re conked out on melatonin themselves. When I don’t hear anything, I tiptoe into Sukey’s old room, avoiding the squeaky floorboard by the door. I find what I’m looking for and hurry back to my room. I throw on a sweatshirt and sling a canvas messenger bag over my shoulder, tucking the contraband inside.

Two minutes later I’m silently wheeling my bicycle through the side door of the garage.

For the first few blocks of the bike ride, my senses are on high alert. Every car that passes is my parents coming to bring me home. Every pedestrian is a neighbor or acquaintance who will call them to report my escape.

She’s out of control!

She’s gone berzerk!

She’s biking in her pajamas!

But I feel more solid than I have in a long time, and more certain. My grip on the handlebars is steady. My wheels roll straight and true. The contents of the messenger bag clink softly against my body, their weight reassuring. By the time I get to the bridge, I’ve stopped worrying about being caught. Ahead of me, the city is still and quiet, the only motion the private dances of the sidewalk trees.

I reach into my bag and pull out the first paint jar from Sukey’s set. Anchoring it against the handlebars with one hand, I unscrew the lid with the other, my bike swerving slightly beneath me. When I get the lid off, I hold my arm out and tip the jar over the sidewalk, and a thin stream of paint pours out in one long thread. I look behind me. A trail of marigold yellow follows me down the bridge.

Hey, Kiri . An echo.

I hear you’re in a band .

“It’s just me and my boyfriend,” I say out loud, then laugh at the weirdness of my voice, after midnight, on the bridge.

I screw the lid back onto the yellow paint jar and drop it back into the messenger bag, steering my bike one-handed as I rummage for another jar. I paint a pink dot on Sukey’s magnolia tree, and twin streams of cobalt and crimson along the bike trail where Skunk and I raced at Stanley Park. I leave an emerald splatter on the pavement in front of the Train Room and a tiny white blossom on the patio outside Skunk’s door, hurrying away on tiptoes before I get caught.

Each time I dip my hand into the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher