![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

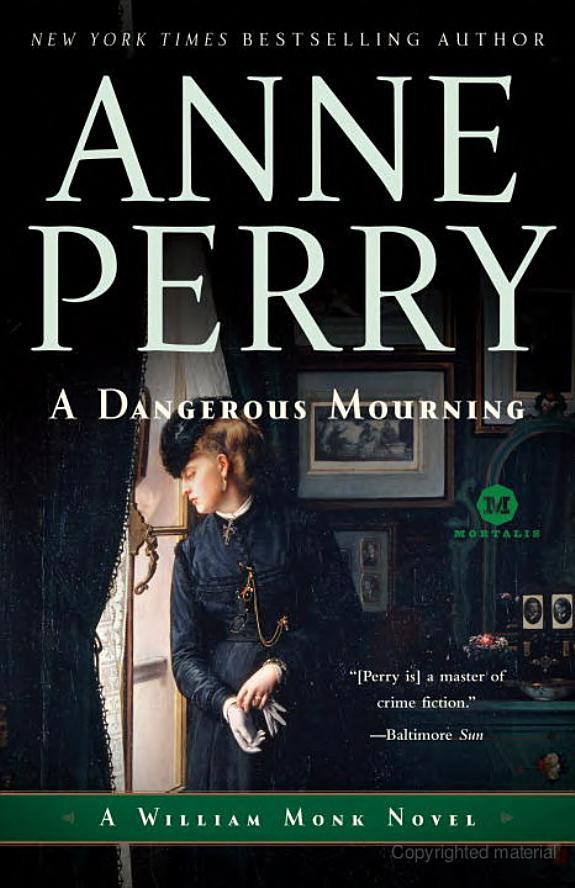

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

tables and his eye fell on a man of perhaps thirty-five, lean and oddly dressed, his face animated, but under the mask a weariness of disappointed hopes.

“I like it here,” he said gently. “I like the people. They have imagination to take them out of the commonplace, to forget the defeats of reality and feed on the triumphs of dreams.” His face was softened, its tired lines lifted by tolerance and affection. “They can evoke any mood they want into their faces and make themselves believe it for an hour or two. That takes courage, Mr. Monk; it takes a rare inner strength. The world, people like Basil, find it ridiculous—but I find it very heartening.”

There was a roar of laughter from one of the other tables, and for a moment he glanced towards it before turning back to Monk again. “If we can still surmount what is natural and believe what we wish to believe, in spite of the force of evidence, then for a while at least we are masters of our fate, and we can paint the world we want. I had rather do it with actors than with too much wine or a pipe full of opium.”

Someone climbed on a chair and began an oration to a few catcalls and a smattering of applause.

“And I like their humor,” Septimus went on. “They know how to laugh at themselves and each other—they like to laugh, they don’t see any sin in it, or any danger to their dignity. They like to argue. They don’t feel it a mortal wound if anyone queries what they say, indeed they expect to be questioned.” He smiled ruefully. “And if they are forced to a new idea, they turn it over like a child with a toy. They may be vain, Mr. Monk; indeed they assuredly are vain, like a garden full of peacocks forever fanning their tails and squawking.” He looked at Monk without perception or double meaning. “And they are ambitious, self-absorbed, quarrelsome and often supremely trivial.”

Monk felt a pang of guilt, as if an arrow had brushed by his cheek and missed its mark.

“But they amuse me,” Septimus said gently. “And they listen to me without condemnation, and never once has one of them tried to convince me I have some moral or social obligation to be different. No, Mr. Monk, I enjoy myself here. I feel comfortable.”

“You have explained yourself excellently, sir.” Monk smiled at him, for once without guile. “I understand why. Tell me something about Mr. Kellard.”

The pleasure vanished out of Septimus’s face. “Why? Do you think he had something to do with Tavie’s death?”

“Is it likely, do you think?”

Septimus shrugged and set down his mug.

“I don’t know. I don’t like the man. My opinion is of no use to you.”

“Why do you not like him, Mr. Thirsk?”

But the old military code of honor was too strong. Septimus smiled dryly, full of self-mockery. “A matter of instinct, Mr. Monk,” he lied, and Monk knew he was lying. “We have nothing in common in our natures or our interests. He is a banker, I was a soldier, and now I am a time server, enjoying the company of young men who playact and tell stories about crime and passion and the criminal world. And I laugh at all the wrong things, and drink too much now and again. I ruined my life over the love of a woman.” He turned the mug in his hand, fingers caressing it. “Myles despises that. I think it is absurd—but not contemptible. At least I was capable of such a feeling. There is something to be said for that.”

“There is everything to be said for it.” Monk surprised himself; he had no memory of ever having loved, let alone to such cost, and yet he knew without question that to care for any person or issue enough to sacrifice greatly for it was the surest sign of being wholly alive. What a waste of the essence of a man that he should never give enough of himself to any cause, that he should always hear that passive, cowardly voice uppermost which counts the cost and puts caution first. One would grow old and die with the power of one’s soul untasted.

And yet there was something. Even as the thoughts passed through his mind a memory stirred of intense emotions, outrage and grief for someone else, a passion to fight at all costs, not for himself but for others—and for one in particular. Heknew loyalty and gratitude, he simply could not force it back into his mind for whom.

Septimus was looking at him curiously.

Monk smiled. “Perhaps he envies you, Mr. Thirsk,” he said spontaneously.

Septimus’s eyebrows rose in amazement. He

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher