![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

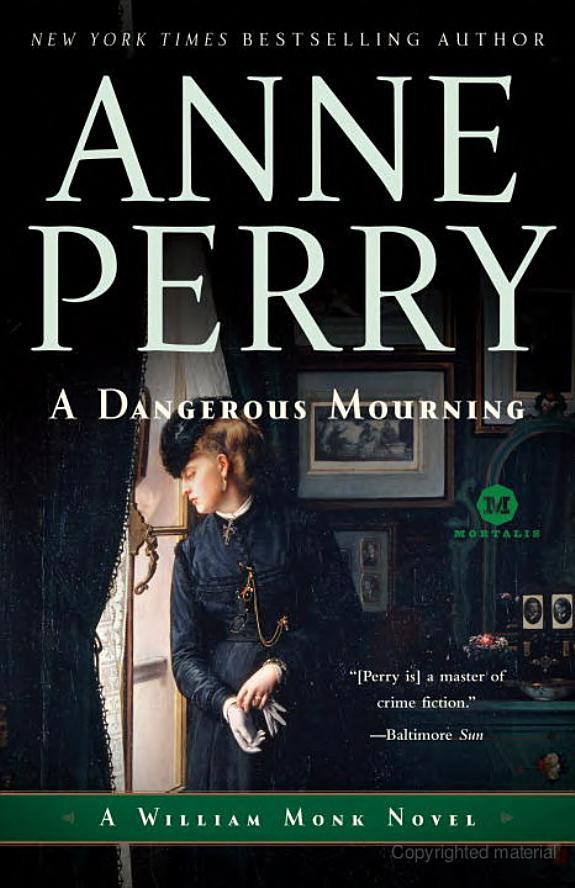

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

past three in the mornin’, but they wasn’t making no nuisance an’ they certainly wasn’t climbing up no drainpipes to get in no winders.” He screwed up his face as if he were about to add something, then changed his mind.

“Yes?” Monk pressed.

But Miller would not be drawn. Again Monk wondered if it was because of their past association, and if Miller would have spoken for someone else. There was so much he did not know! Ignorance about police procedures, underworld connections, the vast store of knowledge a good detective kept. Not knowing was hampering him at every turn, making it necessary for him to work twice as hard in order to hide his vulnerability; but it did not end the deep fear caused by ignorance about himself. What manner of man was the self that stretched for years behind him, to that boy who had left Northumberland full of an ambition so consuming he had not written regularly to his only relative, his younger sister who had loved him so loyally in spite of his silence? He had found her letters in his rooms—sweet, gentle letters full of references to what should have been familiar.

Now he sat here in this small, neat house and tried to get answers from a man who was obviously frightened of him. Why? It was impossible to ask.

“Anyone else?” he said hopefully.

“Yes sir,” Miller said straightaway, eager to please and beginning to master his nervousness. “There was a doctor paid a call near the corner of ’Arley Street and Queen Anne Street. I saw ’im leave, but I din’t see ’im get there.”

“Do you know his name?”

“No sir.” Miller bristled, his body tightening again as if to defend himself. “But I saw ’im leave an’ the front door was open an’ the master o’ the ’ouse was seein’ ’im out. ’Alf the lights was on, and ’e weren’t there uninvited!”

Monk considered apologizing for the unintended slight, then changed his mind. It would be more productive for Miller to be kept up to the mark.

“Do you remember which house?”

“About the third or fourth one along, on the south side of ’Arley Street, sir.”

“Thank you. I’ll ask them; they may have seen something.” Then he wondered why he had offered an explanation; it was not necessary. He stood up and thanked Miller and left, walking back towards the main street where there would be cabs. He should have left this to Evan, who knew his underworld contacts, but it was too late now. He behaved from instinct and intelligence, forgetting how much of his memory was trapped in that shadowy world before the night his carriage had turned over, breaking his ribs and arm, and blotting out his identity and everything that bonded him to the past.

Who else might have been out in the night around Queen Anne Street? A year ago he would have known where to find the footpads, the cracksmen, the lookouts, but now he had nothing but guesswork and plodding deduction, which would betray him to Runcorn, who was so obviously waiting for every chance to trap him. Enough mistakes, and Runcorn would work out the incredible, delicious truth, and find the excuses he had sought for years to fire Monk and feel safe at last; no more hard, ambitious lieutenant dangerously close on his heels.

Finding the doctor was not difficult, merely a matter of returning to Harley Street and calling at the houses along the south side until he came to the right one, and then asking.

“Indeed,” he was told in some surprise when he was received somewhat coolly by the master of the house, looking tired and harassed. “Although what interest it can be to the police I cannot imagine.”

“A young woman was murdered in Queen Anne Street last night,” Monk replied. The evening paper would carry it and it would be common knowledge in an hour or two. “The doctor may have seen someone loitering.”

“He would hardly know by sight the sort of person who murders young women in the street!”

“Not in the street, sir, in Sir Basil Moidore’s house,” Monk corrected, although the difference was immaterial. “It is a matter of learning the time, and perhaps which direction he was going, although you’re right, that is of little help.”

“I suppose you know your business,” the man said doubtfully, too weary and engaged in his own concerns to care. “But servants keep some funny company these days. I’d look to someone she let in herself, some disreputable follower.”

“The victim was Sir Basil’s daughter, Mrs.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher